by David Steven | Oct 20, 2010 | UK

I know Treasury mandarins don’t laugh much, but I suspect a few of them will be smirking on their way home tonight. If I read the spending review right, they’ve pulled a fast one on their bitter, and less numerate, rivals at the Foreign Office – something that is sure to cause an immense feeling of satisfaction.

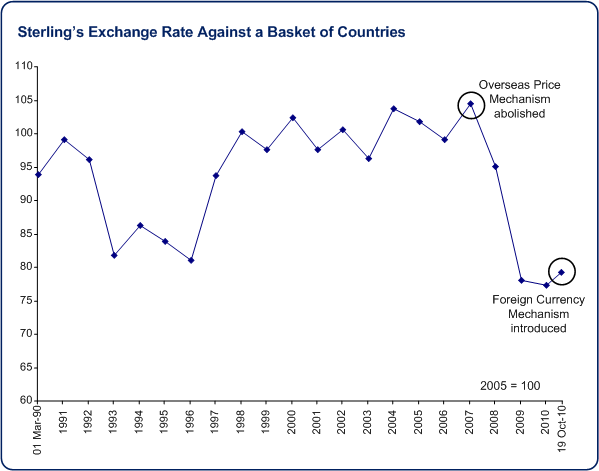

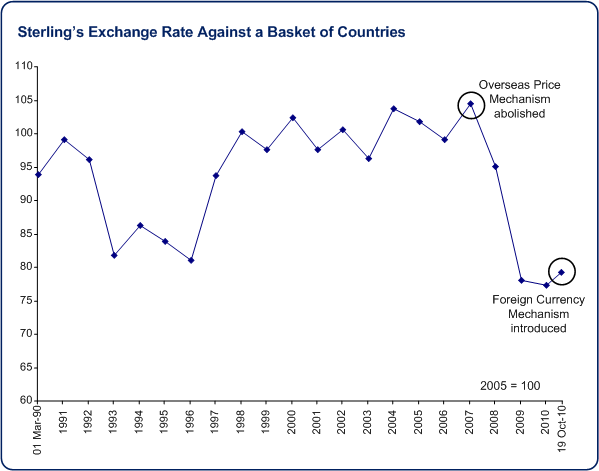

The crux of the matter is in who bears the risk of currency fluctuations. The FCO spends most of its money overseas, so its costs rise when the pound is weak, fall when it is strong.

Historically, the Treasury has evened this out through the Overseas Price Mechanism. The FCO was given money in sterling and, if it found that this was worth more than expected overseas, it gave money back to the Chancellor. If the settlement was worth less than expected, it was given sufficient extra funds to enable planned activity.

In the mid 2000s, the tide was in the Treasury’s favour, with £5-14 million a year being returned by the FCO, but in 2007/08, the pound began to weaken and HMT had to pay the FCO £1.5 million or so.

The Treasury didn’t like this, so it abolished the price mechanism and left the FCO to deal with an increasingly feeble pound. The result was carnage. The FCO lost £100m in 2008/09 and the same again in 2009/10.

According to the Foreign Affairs Select Committee:

The FCO has lost around 13% of the purchasing power of its core 2009–10 budget as a consequence of the fall of Sterling. We concur with the National Audit Office, that the withdrawal of the Overseas Price Mechanism and the subsequent fall of Sterling have had “a major impact on the FCO’s business worldwide”.

We note that the budgetary transfers which the FCO has made to try to help cope with the hit have absorbed all of the Department’s contingency reserve at the Treasury in both 2008–09 and 2009–10, and we conclude that this represents an unacceptable risk to the FCO’s ability to perform its functions.

So today’s announcement that currency risk is being passed back to the Treasury is a big coup, no? Certainly, the new ‘Foreign Currency Mechanism’ will give greater certainty to FCO staff, but the re-introduction comes at a time that is highly disadvantageous to our diplomats.

Look at this graph showing the pound’s value against a basket of currencies. Currency risk was dumped on the FCO just as the pound was about to begin a long, hard fall. It’s now been taken back by HMT at what looks like the currency’s trough.

Worst case for HMT, the pound’ll bump along the bottom. Best case, it’ll strengthen and they can demand a big fat cheque from William Hague. It’s the first rule of markets – sell high, buy low – especially when you want to turn the screw on your next-door neighbours.

by David Steven | Oct 20, 2010 | UK

I am at Sky News for on a panel of experts (find some of them on Twitter here), covering the international beat (diplomacy, development, any fallout from yesterday’s defence review etc).

Not expecting many of the headline issues to be on my patch – ironic given that the UK is in a mess because of risks that hit it from overseas: 9/11 and all the dumb things we did as a result of Bin Laden’s provocation; the food and fuel price spike; and the global economic crisis.

Anyway – Osborne is speaking now: it’s time to pull Britain back from the brink. Updates whenever global makes a showing…

Update: In 2014/2015, George Osborne tells the House, the UK will be paying £63bn in debt. I’d expect the UK to be spending considerably less than £60bn on its entire international programme (defense included).

Update II: George Osborne says that 490,000 jobs will be lost over four years. (Next to me, Chris Dobson from PWC says that another 500,000 jobs will go in the private sector as a result of government cuts)

The Chancellor promises to sack as few people as possible – which means, I expect, a near-total recruitment freeze. But, at the same time, he wants root-and-branch public sector reform. That means departments will have to take on new responsibilities, without being able to hire in new skills.

Sclerotic government anyone?

Update III: We’re onto defense. MOD gets £33.5bn in 2013/14 an 8% cut – plus whatever Afghanistan needs. 24% cuts for the FCO by taking a hatchet to HQ staff (because strategic synthesis on global issues doesn’t matter as much as ‘commercial diplomacy’).

DFID has been told its admin costs down to half of what other donors spend (which means not enough staff to work in fragile states). Programmes in China and Russia are to be abolished.

Update IV: The FCO loses around £530m (about half the cost of a new Type 45 destroyer) – but £240m of that is accounted for by the World Service, which will now be paid for by the BBC license fee payer. So the big question is, how much of the other £287m is real money? See update VII for more.

Things to look for – how much development assistance will the FCO get to spend? Will parts of the Council budget be paid for by DFID?

Update IV: All British Council grant-in-aid will continue to be funnelled through the FCO. The Council sees a cut of around £30m over four years – around 18% of its current budget. BC head, Martin Davidson says its a ‘reasonable settlement.’

Update V: Looking at the full spending review report, now. FCO gets protection from exchange rate fluctuations. It will also get a chunk of the increase in development spending. Probably the big surprise is that is cuts are heavily backloaded. It doesn’t lose anything at all until 2013/14…

Update VI: Talked to DFID press office. They’re aiming to half adminstration costs – taking them 4% of total spending (which is about average for donors) to 2%. That measn £15m of cuts – £8m on ‘back office’; £2m off the wage bill; £4m by leasing three floors of their building out; and £3m by making their staff travel economy.

Update VII: The FCO loses £200m in cash terms over four years but the cut happens in the last year – there’s a small cash increase before that. I now think the cut is almost wholly accounted for by the transfer of the World Service to the BBC which does not happen until 2013/14. The ‘real’ cut is 24% – but that, of course, depends on the rate of inflation. I was told before the announcement that the FCO would be pretty happy with flat cash. Still not 100% sure what’s and out of the figures though, and am waiting for the FCO press office to clarify.

Update VIII: This is it for me – unless more news unexpectedly emerges. But one final reflection on the FCO… When we wrote our Chatham House paper, the most contentious issue was what to do with the FCO’s central operation – expand or gut it.

Looking to the future, we see two options for the department:

- A back-to-basics reform of the FCO, paring the department back to focus on its traditional core business of (i) running a network of embassies, (ii) providing a geographical perspective on policy to the rest of government, and (iii) offering consular services to UK citizens.

- Radical reform that would rebuild the FCO’s London headquarters around the primary role of strategic synthesis on the UK’s global issues objectives – a role that would enlarge its responsibilities and bring it much closer to the centre of government, but require far-reaching operational changes – while still firmly maintaining the FCO’s in-country expertise.

Many will see reasons to support the first option. The FCO excels at this work, and would probably prefer to stay in the comfort zone of its overseas network and bilateral relationships. Recent years have shown that global issues are far from being a core concern for the department (with climate change as a notable exception)…

However, we fear that this route would lead to an ongoing downgrade and marginalization of the existing FCO – and would still require the same strategic synthesis and campaigning capacity to be created elsewhere in government.

We therefore believe that William Hague should explain to his new department that it must be prepared to consider far-reaching steps to secure its future, developing a strategic role at the heart of the government’s response to globalization’s long crisis. This means that at least 50% of the mid-level and senior staff working on policy issues at its London headquarters should be seconded from other government departments – making the FCO less like other Whitehall line departments and more like the Cabinet Office.

This shift would both ensure an effective mix of issue and geographic expertise, and begin the process of transforming the FCO into a department able to use its geographic network to respond effectively to global issues.

Clearly, we now have an FCO burrowing deep back into its comfort zone – but I expect we’ll be back asking the same questions about strategic synthesis on global issues the next time a big crisis hits.

Update IX: On aid, the big year is 2013, when expenditure is expected to suddenly leap from 0.56% of GNI to 0.7%. If the 0.7% commitment is ever to be dropped, it’ll be then.

Looking to the future, we see two options for the department:

A back-to-basics reform of the FCO, paring the department back to focus on its traditional core business of (i) running a network of embassies, (ii) providing a geographical perspective on policy to the rest of government, and (iii) offering consular services to UK citizens.

Radical reform that would rebuild the FCO’s London headquarters around the primary role of strategic synthesis on the UK’s global issues objectives – a role that would enlarge its responsibilities and bring it much closer to the centre of government, but require far-reaching operational changes – while still firmly maintaining the FCO’s in-country expertise.

Many will see reasons to support the first option. The FCO excels at this work, and would probably prefer to stay in the comfort zone of its overseas network and bilateral relationships. Recent years have shown that global issues are far from being a core concern for the department (with climate change as a notable exception)…

However, we fear that this route would lead to an ongoing downgrade and marginalization of the existing FCO – and would still require the same strategic synthesis and campaigning capacity to be created elsewhere in government.

We therefore believe that William Hague should explain to his new department that it must be prepared to consider far-reaching steps to secure its future, developing a strategic role at the heart of the government’s response to globalization’s long crisis. This means that at least 50% of the mid-level and senior staff working on policy issues at its London headquarters should be seconded from other government departments – making the FCO less like other Whitehall line departments and more like the Cabinet Office. This shift would both ensure an effective mix of issue and geographic expertise, and begin the process of transforming the FCO into a department able to use its geographic network to respond effectively to global issues.

by David Steven | Oct 20, 2010 | Conflict and security, Economics and development, UK

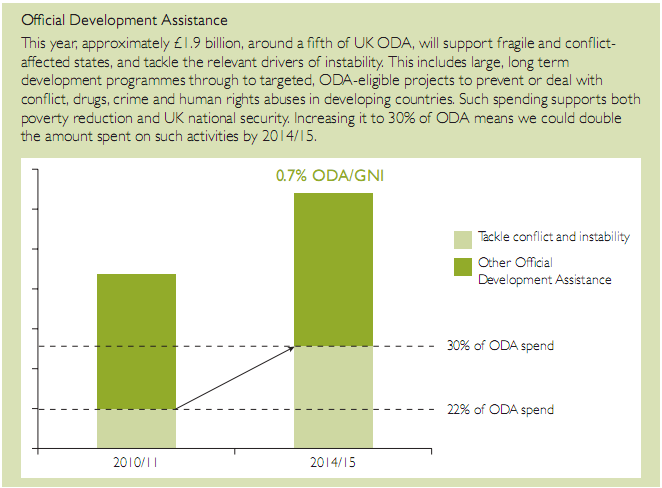

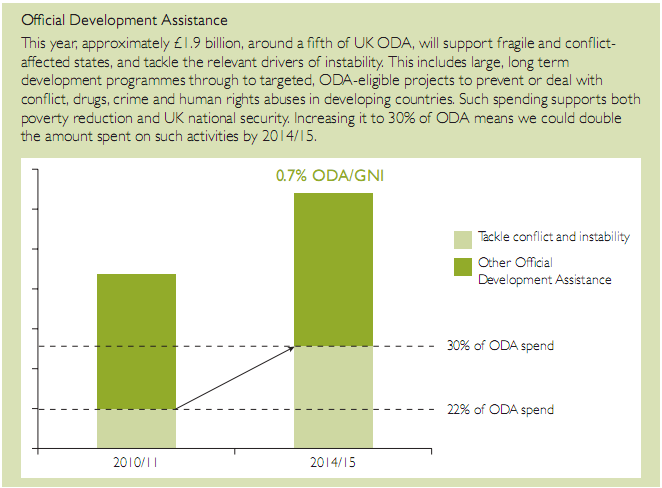

For DFID – the heart of yesterday’s defence review was a new commitment to spend 30% of Britain’s development cash on “priority national security and fragile states”. This box explains what that means in cash terms…

Alex and I argued for this policy in our Chatham House paper. DFID, we wrote, should be turned into the world leader in tackling the problems of fragile states.

But there was a quid pro quo. Fragile states need lots and lots of high-level expertise – not oodles of dosh. But DFID is probably going to be forced to make job cuts as a result of the spending review. So it’s going to have more money, tougher challenges to deal with, but fewer people. Something has to give.

The solution, we argued, was for the government to “make it clear that where a poor country’s main need is financial, the UK will not necessarily maintain a country office – but will instead reduce transaction costs by partnering with other effective donors, or simply channeling funds through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.”

So far, the coalition has seemed fairly cool on the multilateral system – but if it wants to do a good job in fragile states, this has to change. Clearly, the FCO and MOD are hoping they will directly spend a big chunk of the UK’s development money, but DFID still needs to think hard about how best to deploy is scarcest resource – the expertise of its dwindling staff…

by David Steven | Oct 18, 2010 | UK

Beyond sharing the ‘age of uncertainty’ title, the UK’s new national security strategy overlaps considerably with the Chatham House report on British foreign policy that Alex and I published just after the election.

The Cameron/Clegg introduction is based on the same understanding of global challenges as set out in the first chapter of our report. The strategy is based on a risk management approach (good) and a wish to build resilience (even better – the Conservatives were exploring resilience as a theme during their time in opposition).

But where we diverge from the government is in the proposed response. Like the government, Alex and I are interested in countering direct immediate and direct threats to British citizens (the core national security agenda). We are also keen to support the weak links in the global system – fragile and failing states (the core development agenda).

But our third area of strategic focus centres on an attempt to persuade others that urgent efforts are needed to rebuild the global system itself – rather than to try and wait out globalization’s ‘long crisis’. For us, this is the heart of modern foreign policy.

Although the NSS talks a good game about preventing risks before they hit the UK, it does little to flesh out what it means by ‘shaping the global environment’ to manage risks. And the FCO seems to be fast losing interest in this agenda. Instead, we are promised that foreign policy can be turned into a money-earner and that “the [overseas] networks we use to build our prosperity we will also use to build our security.”

The implications of this commercial focus aren’t spelled out in the strategy, but what it means in practice is that Embassies are going to be judged increasingly by the time they spend trying to win contracts for British businesses. My reaction to this prospect is visceral (lots of swearing and Basil Fawlty-style leaping around). Here, though, are some more measured objections:

- I don’t think it works – big business has sophisticated networks overseas and there are many private sector providers of risk and political analysis. Why on earth would the Ambassador be decisive in sealing the deal – let alone one of his lesser minions? And if our Ambassadors are such commercial whizzes, why on earth wouldn’t businesses want to pay for their services (or for that matter, poach them from their poorly paid jobs)?

- It’s an essentially zero-sum activity – pitting the UK against its allies precisely in those parts of the world where we need to forge a common cause. Partnership gets fairly short shrift in the NSS – but the UK’s most pressing problems will only be solved through collective action. Try and wish that away if you like, but it’s a cold, hard fact.

- Business objectives will always clash with other more important goals. Business lobbies trump free trade agreements, financial regulation, climate deals, tough lines on corrupt states etc. As we have seen, many boards would happily screw the global economy if it meant meeting the next quarter’s targets. Thatcher did sterling work getting the state out of business. Some day we need a PM with the guts to prise business out of the state.

- Scandal is inevitable. The NSS can talk about British values as much as it likes, but, soon enough, politicians and officials will start to cross ethical lines. Before you know it, the Conservatives will have another Arms to Iraq on their hands – or be embroiled in a BAE-style mess. Try telling us that ‘our core values are not open to question’ then.

I expect the commercial focus will prove to be a fad – to be swept away when the next big international shock hits our shores. But the diversion is damaging, because it has stopped the coalition getting serious about global issues. And that, I predict, will prove to be a big mistake…

by David Steven | Oct 18, 2010 | UK

Evans and Steven, Chatham House, June 2010:

UK National Security Strategy, HMG, October 2010: