by Alistair Burnett | Oct 8, 2010 | Conflict and security, Global system, UK

Three weeks, three party conferences, but what did they tell us about where the parties see Britain’s place in the world?

First up were the Liberal Democrats in Liverpool.Their first conference as a party of government and junior Foreign Office Minister, Jeremy Browne, who described himself as the longest serving Liberal in the Foreign Office since 1919, gave the foreign affairs speech.

He made the now obligatory reference to the rise of China, India, Brazil and other powers and said Britain and Europe can’t stop this, but instead should seek to make it a force for good.He also argued that Britain still has a lot to offer and should be a catalyst for this new world order. It was short on specifics or examples of how this could be done, and how different is this from David Miliband’s talk when he was Foreign Secretary, that Britain should be a ‘global hub’?

The Lib Dems’ junior Defence Minister, Nick Harvey, focussed on one of the party’s keynote policies – a review of the need for a like-for-like replacement of Trident. In his speech, Nick Harvey argued for delaying the decision until after the next election, but his reasons appeared less about giving more time to consideration of the options and more about wrong footing the Labour Party. An argument that could give the impression that debate on a fundamental issue like the future of Britain’s nuclear weapons capability is being used as a tool to embarrass political opponents.

Next to Manchester and Labour’s conference. Being the first since losing power, it, perhaps understandably, witnessed quite a bit of raking over the recent past – both from internal critics of the last government and from former ministers defending their records.

A fringe meeting on the future of defence policy I went to heard concerns from trade unions and defence contractors about the potential impact on jobs and the industrial base of the defence cuts expected from the ongoing Strategic Defence and Security Review. The former Defence Secretary, Bob Ainsworth, was on the panel and on the defensive, responding to questions about his record with jibes back at some of his questioners.

The thing lacking was much discussion of what kind of role Britain should play in the world and what kind of military forces will be required for that. The defeat of David Miliband for the leadership and his decision to return to the backbenches inevitably meant there was less focus on his foreign policy speech to the conference than on discussion of his legacy, including as Foreign Secretary. On The World Tonight, journalist Ann McElvoy argued his main legacy was that in the wake of the Iraq war, which many believe was a big mistake, he made the case for Britain to retain its global reach and the need for intervention when the time is right, especially in Afghanistan.

On to the Conservatives in Birmingham.In the wake of the leak to the Daily Telegraph of Defence Secretary Liam Fox’s letter to David Cameron arguing against deep cuts to his budget, the mood among the Tories’ defence team seemed more upbeat, suggesting their rearguard action ahead of the Comprehensive Spending Review may be having some success. And, almost inevitably, discussion over Britain’s role in the world at the conference was dominated by the defence review as it nears completion.

The defence fringe I went to was a bit more wide-ranging than its Labour equivalent. The Defence Minister, Peter Luff, said the government is looking to France to be a strategic partner along with the US. He also suggested Britain would seek to work with France to develop new weapons systems bi-laterally, rather than enter new multilateral projects like the Eurofighter ‘Typhoon’. But the argument over what role Britain should play in the world came mainly from Nick Witney of the European Council on Foreign Relations rather than the politicians on the panel.

All this left me thinking that if the party conferences reflect the way the main parties are looking at Britain’s future global role, it does seem their focus is still very much on the defence review and cuts, rather than the more fundamental question of what role the UK should play in the changing world order. If there is a wider debate going on about what the UK’s military forces should be for, rather than simply what can be afforded, it seems to be going on largely behind the scenes. Whether that is wise is another matter.

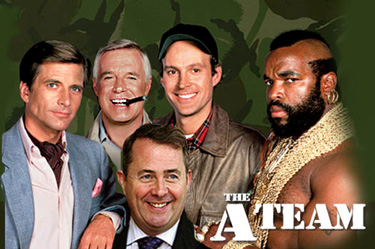

by Alex Evans | Oct 4, 2010 | Conflict and security, UK

Currently doing the rounds in Whitehall:

As part of budget cuts the entire Ministry of Defence is to be dismantled and replaced by four soldiers of fortune sent to prison for a crime they didn’t commit.

‘We need a leaner, less centralised MoD,’ said Defence Secretary Dr Liam Fox, ‘and the A-Team are the perfect replacement. We were committed to spending billions on Trident but these guys have already managed to build us an independent nuclear deterrent using a broken lawnmower, two cans of WD40 and a thighmaster they found in my garage.’

Dr Fox is understood to have got the idea after seeing an advert in the back of Guns & Ammo magazine: ‘If you have an unsustainable budget deficit, if no one else can help, and if you can find them, maybe you can hire…The A-Team.’

‘We are delighted to be helping the British government tackle their deficit,’ said the new head of British Armed forces Lieutenant Colonel John ‘Hannibal’ Smith, adding, ‘I love it when a strategic defence review comes together.’

Lieutenant Templeton ‘Faceman’ Peck will handle weapons procurement; the new head of the RAF becomes Air Chief Marshal ‘Howling Mad’ Murdock; meanwhile B.A. Baracus will supply British troops in Afghanistan with essential supplies of milk and Snickers.

To save on costs, the MoD offices in Whitehall will be sold off and replaced by a specially adapted GMC Vandura van with a built in missile launcher that can be sent to trouble spots around the world.

The A-Team have already pledged to resolve the situation in Afghanistan by driving round the country at tremendous speed and blowing everything up. However, unlike previous invasions, they have promised to get things sorted in under an hour (with ad breaks) with miraculously no loss of life.

The team are expected to fly out to Kabul next week, or just as soon as they manage to persuade B.A. Baracus who is currently refusing to budge saying only, ‘I ain’t getting on no underfunded neo-imperialist campaign, fool. Or Easyjet.’

Shadow Defence Secretary Bob Ainsworth criticised the government. ‘These guys are a bunch of mercenary criminals and one of them is certified insane,’ he said, ‘and the A-Team isn’t much better.’

With thanks to CE.

by Alex Evans | Aug 16, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

Lots of agitation on the internets this weekend with news of cancellation of various DFID funding priorities. It all seems to stem from this leaked submission from DFID’s Policy Director, Nick Dyer, on the subject of “which previous public commitments DFID should track and honour”.

The new government took office with over a hundred such commitments on the books, the submission notes – before recommending keeping just 19 of them (including, thankfully, the £1 billion for food and agriculture and the £1.5 billion for fast start climate finance). Here’s the list of which commitments the submission proposes dropping.

Cue predictable howls of outrage from, well, everyone you’d expect (see this post on Left Foot Forward, and this Observer piece from over the weekend), plus an accusation from Caroline Crampton in the Statesman that “a silent withdrawal from the ringfencing policy seems to be underway”.

Well, hmmm… I’m not so sure. I have questions of my own about where Andrew Mitchell is taking DFID – I really hope the ultra-low profile he’s been keeping on big global policy issues like climate change is a reflection of a tactical decision to lie low until after the Spending Review, rather than a ‘new normal’; I’m seriously worried about what’ll happen to DFID’s headcount if its admin (rather than programme) budget is deemed eligible for the 25-40% cuts other departments are facing, given that DFID’s lost 1 in 6 staff since 2005 as it is; and of course I disagree with some of the items included on the proposed cancellation list (Gareth Thomas is right, for example, that cancelling funding to CERF would be a seriously bad idea, and would undermine the UK’s track record of leadership in pushing for a more coherent and effective UN humanitarian assistance system).

But overall, the howls look a bit overdone to me. For one thing, reviewing how DFID spends its budget is not the same as undoing the ringfencing over the size of that budget (as Caroline Crampton must realise). There’s no sign of the coalition backing away from its commitment on 0.7, and I honestly can’t see them doing it after all the political capital they’ve committed on the issue (for sure, there are questions about what else may be counted as aid, but that’s not what this submission is about).

More fundamentally, it’s legitimate to question some of these funding commitments. How exactly are we honouring the principle that developing countries get to decide how to spend the aid the UK gives them, if ministers keep announcing one sectoral fund after another? And what about the fact that a good few of the items on the proposed list of cancellations were the result not of careful policymaking, but of Gordon Brown phoning up DFID and demanding an announceable (usually less than 24 hours before a speech)?

Me, I think the jury’s still out on Andrew Mitchell. The themes he’s developed so far – transparency, outputs and outcomes, accountability – are all OK as far as they go, if a bit boring. I don’t see the outlines of his ‘grand strategy’ on development yet, but hopefully we’ll hear more about that in the autumn. In the meantime, reviewing where DFID’s money goes and which of the ancien regime‘s commitments he’ll retain seems not unreasonable to me.

by Richard Gowan | Aug 11, 2010 | Africa, Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, East Asia and Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, South Asia

Michael Mandelbaum summarizes his new book, Frugal Superpower, for The New Republic. From now on, “the United States will have far less to spend on foreign policy because it will have to spend far more on other things.” What does that mean?

The government will still have an allowance to spend on foreign affairs, but because competing costs will rise so sharply that allowance will be smaller than in the past. Moreover, the limits to foreign policy will be drawn less on the basis of what the world needs and more by considering what the United States can–and cannot–afford.

In these circumstances, the public will no longer feel able to afford, and so will not support, operations to rescue people oppressed by their own governments and to build the structures of governance where none exists. Interventions of this kind, which the United States has undertaken in the last two decades in Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq, will not be repeated. The American defense budget will come under pressure, and so, too, therefore, will the missions that the defense budget supports: the American military presence in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East.

Here the impact of the coming economic constraints on foreign policy will differ from the effects of the downsizing of the financial industry. Reducing the size of banks and other financial institutions will have benign consequences, reducing the risk of a major economic collapse, limiting economically unproductive speculation, and diverting talented people to other, more useful, work. By contrast, the contraction of the scope of American foreign policy will have the opposite effect because the American international role is vital for global peace and prosperity.

The American military presence around the world helps to support the global economy. American military deployments in Europe and East Asia help to keep order in regions populated by countries that are economically important and militarily powerful. The armed forces of the United States are crucial in checking the ambition of the radical government of Iran to dominate the oil-rich Middle East. For these reasons, the retreat of the United States risks making the world poorer and less secure, which means that the consequences of the economically-induced contraction of American foreign policy are all too likely to be anything but benign.

Where do we go from here? Last month, I wrote an op-ed for Global Europe in which I argued that while the U.S. and EU are suffering in the current economic environment, they’re not alone. Russia is also feeling the pain – as Alistair underlines in his recent post – and has moderated its foreign policy as a result. China and India enjoy stellar growth and are willing to challenge the U.S., especially in their backyards. But their ability to project long-range military power remains limited for the time being.

All the rising powers are increasing defence spending, while European military cost-cutting will likely continue well beyond the immediate downturn. But for now, we are in a moment when everyone looks weak. If the U.S. and its NATO allies are wary of projecting power, the big emerging economies still have limited reach.

In some ways, this is rather nice. Great power confrontations are not impossible, but are still relatively improbable. Yet this era of weakness also bring risks. The most obvious are in the Middle East. With the U.S. gradually pulling back from the region, a breakdown in Iraq or spillover of violence from Afghanistan could create endemic instability. Israel, uncertain of U.S. support, has become increasingly hawkish. State failures and civil wars will continue to bubble from Sudan to Central Asia. If the Afghan experience has convinced many that interventionism is foolish, ignoring these crises is dangerous. Remember why we went into Afghanistan in 2001.

Containing new crises will be difficult. Instead of Bush-era “coalitions of the willing”, it may be necessary to form “coalitions of the weaklings”: groups of states that can’t handle international problems alone, but have sufficient leverage between them to do something.

“Coalitions of the weaklings” may sound snappy, but what will they look like and what will they achieve? The rather rickety international alliances put together to deal with Iran and North Korea aren’t exactly inspiring models for future cooperation. Nor is the Sino-US-AU-EU arrangement for dealing with Sudan likely to excite idealists… plus such coalitions are also hard to stick together and sustain. In a recent piece for World Politics Review (subscription required) Bruce Jones and I came to this conclusion:

In the future, resolving looming conflicts will more often than not involve convening highly complicated — and inherently unstable — coalitions of governments to put pressure on potential combatants. Regional organizations, like the African Union and Organization of American States, also have leverage. But who will do the convening?

Sometimes, the U.S. will still take the lead, or else regional powers will do so. But in many cases, the competing interests involved in a crisis will preclude a single state from orchestrating mediation. In such instances, the task of leading talks — or backing up local actors with better political contacts to do so — may fall to a much-maligned actor: the United Nations.

A prospect that will fill you with hope or dread, depending on your convictions…

by Alex Evans | Jul 15, 2010 | Influence and networks

About a quarter of a billion people spend time every week inside some kind of virtual world (like World of Warcraft, or Second Life, or IMVU). That’s one of the arresting statistics in an extraordinary talk on virtual worlds given by Rohan Freeman last November, reproduced in full at the end of this post.

Freeman doesn’t like the term ‘virtual’ to describe what he terms the ‘metaverse’, arguing that “it is meaningless in this context. These ‘virtual’ worlds are real. Just as an MP3 file is real, a phone call is real and the intellectual property vested in a Gucci handbag is real. Ideas are real. People are being found guilty of real crimes in real courts if they steal ‘virtual goods'”. Above all, the relationships forged in the metaverse are real:

Let me give you an example from personal experience. When I first started to investigate virtual worlds I bought a small piece of land and I had a neighbour on each side. My neighbour on one side was a single mother, living in a town in Scotland. She was on income support, living in council accommodation, she had no qualifications and was struggling to keep her two sons from playing truant. My neighbour on the other side was a Director of The National Physics Institute. And they knew each other. And she was reading some papers of his, talking about plans they have to create a constellation of satellites that can better measure climate change.

Two years ago, by her own statement, she spent her days watching Ricky Lake. One year ago she was playing online bingo. Now she lives in virtual reality. She could have found his papers on Internet anyway. She could have gone to the library and requested them there. But the reason she was reading his papers was; she met him. They literally struck up a conversation over the garden wall. The presence of their avatars in a shared space changed things psychologically for both parties.

One of the most significant things about the metaverse, he continues, is how effective it is at creating trust – so much so that people fall in love there, the whole time. This is different from other social networking technologies. “People don’t fall in love on Facebook. It’s not really that easy to fall in love on the phone.” Why? In a nutshell, he argues, because of bandwidth. That’s why, after all, people still like to meet face to face:

When we meet face to face and communicate with each other we inevitably give away thousands of things about ourselves; thousands of tells, our body language and the direction of our eyes, how we respond to the space occupied by other people. Other people pick all this up, both consciously and unconsciously. And this is the basis of trust. We know we all give things away about ourselves when we meet. And that allows us to evaluate each other and take a decision; I trust this guy with my life. I don’t trust him with my life but I trust his opinions on Japanese cinema. I wouldn’t trust him to find his own arse with both hands.

Move that process to the telephone and it’s harder. There is considerably less unwitting information on which to base a decision. Move it to an email it gets harder still. Reduce the bandwidth that dramatically and you necessarily reduce the information on which to base decisions of trust.

But a live 3D metaverse? Very different story.

It’s live; so if someone starts spouting off about what the don’t like about a movie, for instance, then people can gather round if they want and respond in real time. And if I want to be a part of that, the first step to engagement is so low that anyone can take it. I just need to stand near them and listen. I don’t even need to say anything to begin to feel like part of the discussion. I might, after a few minutes, volunteer a ‘”LOL”when someone else says something funny. Maybe I’ll chime in on a comment with others. I might just stand around and take it all in.

The entry barrier being much lower, far greater social liquidity and subtlety is created. It may not seem like I contributed a great deal to the conversation by chipping in with a “LOL” half way through. But my presence, my attention, my occasional displays of alertness created context for everyone else. I was part of what brought other people over to hear this guy. They saw me and a few others. And he was encouraged because he could see people like me paying attention and laughing. I can only repeat; it’s all real.

(more…)