by Leo Horn Phathanothai | Dec 4, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development

Here’s what the world looks like if country sizes were proportional to their emissions (world map scaled to fossil-fuel carbon-dioxide emissions in 2002):

And here’s what the world looks like if countries were sized commensurately with the burden of climate change impacts (world map scaled by the World Health Organization’s regional estimates of per capita mortality from late 20th century climate change):

These maps were drawn from the recently released UN Population Fund (UNFPA) ‘State of World Population 2009’ report, which focuses on the theme of women, population and climate change. While the developed countries have contributed the most to human-induced climate change up to now, people in poor countries—most dramatically in Africa—already are much more likely to die as a result of the climate change that occurred up to 2000.

The picture is significantly more skewed if we were to take account of (i) historical emissions; (ii) the unequal burden of future climate impacts.

by Alex Evans | Dec 3, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Influence and networks

With three days to go until Copenhagen begins, there’s increasing awareness that the likeliest scenario is that Copenhagen will fail to produce a robust deal on climate change. So here at Global Dashboard, we thought we’d run a series of posts that start us out on thinking about what comes next. If Copenhagen isn’t destined to succeed, then what are the ways in which it could fail? Which failure scenarios leave us in better shape for success at a later date? What does success actually look like? And how can we get there from where we are now?

So let’s start with how it could go wrong. We think there are three ways that the summit itself could fail – and two additional ways in which it could fail over the longer term. Start with what could go wrong in Copenhagen:

– First, we could see a Bali #2 – in other words, talks conclude with a high level political declaration that’s spun as a breakthrough, but that actually has little more content than the Bali Action Plan that negotiators agreed in 2007. All the tough issues would be deferred to a COP15 bis follow-up conference, or indeed to COP16 in December 2010 – or for that matter to an ongoing process like the Marrakech talks that followed Kyoto to hammer out the technical ‘rule book’.

– Second, we could find ourselves facing a Bad Deal – a situation in which a headline deal (with actual numbers) is agreed, but ambition is far below what’s needed to put the world on track for average warming to stay below two degrees C.

– Third, we could end up in a Car Crash – a scenario in which the talks end in outright collapse, with or without a commitment to keep talking.

As important as how the summit itself could fail, though, is the question of what happens next. One possibility is that failure at Copenhagen leads to a breakthrough, which is then followed by smooth and successful implementation (Good Deal). But two rather less attractive scenarios are also possible:

– First, the process could become the Multilateral Zombie that we talked about in our paper (pdf) on climate institutions earlier in the year: so despite efforts to resurrect the process at a COP15 bis (or later in the process), the requisite political will never materialises, and the UNFCCC process becomes a zombie – staggering on, never quite dying – just like the Doha trade round before it.

– Alternatively, it could succumb to Death by Climatocracy – in which an apparently ambitious deal fails during implementation, with inadequate attention paid to the supporting institutional infrastructure, and the deal slowly collapsing under the weight of its own complexity.

In our next posts, we’ll look at what might prompt a slide into any of these scenarios, and at what policymakers and campaigners can do about it.

But for now, one parting thought: not all failures are equal. Some outcomes boost the prospects of eventual success. Others, as discussed above, push the climate process towards semi-permanent dysfunction, an equilibrium that may only be shifted by future climate catastrophe.

It’s time to start looking failure in the face – and asking which kind of failures could be used as the springboard for meaningful action, and how.

Find Part 2 of this series here.

by Alex Evans | Dec 3, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity

The FT’s leader on Copenhagen this morning was exactly right. First it trashed the CDM (see here for CDM-trashing here on Global Dashboard over the last two years):

The CDM inherits the UN’s suffocating bureaucracy, so smaller projects struggle to gain approval. But more important than what it keeps out is what it lets in. The criterion of “additionality” is supposed to rule out projects that would not be undertaken without CDM payments. Not only is this counterfactual approach utterly unverifiable; it is also an ideal target for gaming.

And then it suggests an approach based on a stabilisation target, a safe global emissions budget, and binding targets for all allocated on the basis of ultimate convergence to equal per capita entitlements as what we should be doing instead (ditto):

…the solution to the CDM’s problems is more carbon trading, not less. It matters little for the climate where or what activities greenhouse gas emissions come from. But it matters enormously for the cost of cutting them. That is why the best solution is a global emissions cap and tradeable national quotas (ultimately based on equal per capita amounts) coupled with a scientific mechanism for measuring national emissions.

Bravo, FT. Expect my subscription renewal forthwith.

by Alex Evans | Nov 14, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Influence and networks

Front page splash on The Times this morning:

Less than half the population believes that human activity is to blame for global warming, according to an exclusive poll for The Times.

Only 41 per cent accept as an established scientific fact that global warming is taking place and is largely man-made. Almost a third (32 per cent) believe that the link is not yet proved; 8 per cent say that it is environmentalist propaganda to blame man and 15 per cent say that the world is not warming.

Tory voters are more likely to doubt the scientific evidence that man is to blame. Only 38 per cent accept it, compared with 45 per cent of Labour supporters and 47 per cent of Liberal Democrat voters.

Similarly depressing polling data a month ago in an FT / Harris poll:

Fewer than a third of people in the UK and only one in five in the US were in favour of developed countries offering aid to the developing world to help them adapt to the effects of global warming, the Harris poll showed.

In the US there was strong opposition to such aid – four in 10 people were against, compared with about a quarter in the UK, and 17-19 per cent in continental Europe.

From the same poll:

When it came to apportioning the burden of cutting emissions, people were clear that China, as the world’s biggest emitter, must make most of the effort required.

A majority in all countries was in favour – 63 per cent in the UK and the US, with higher percentages in mainland Europe – and fewer than 10 per cent in each country disagreed.

by Alex Evans | Nov 11, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global Dashboard

I’ve said before that the easing of oil and food prices that followed the credit crunch and the global downturn gave policymakers a window of opportunity to take preventive action on scarcity issues. Now, alas, I think that window is starting to close – without their having done much about it.

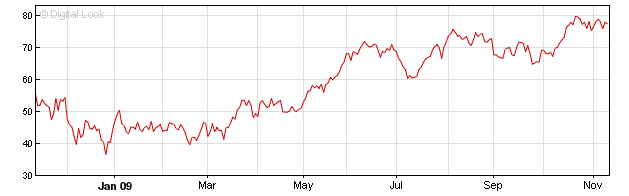

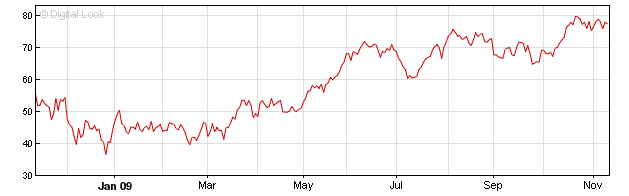

To see why, first take a look at what the oil price has been doing over the last year (Brent crude futures, $/barrel; h/t BBC):

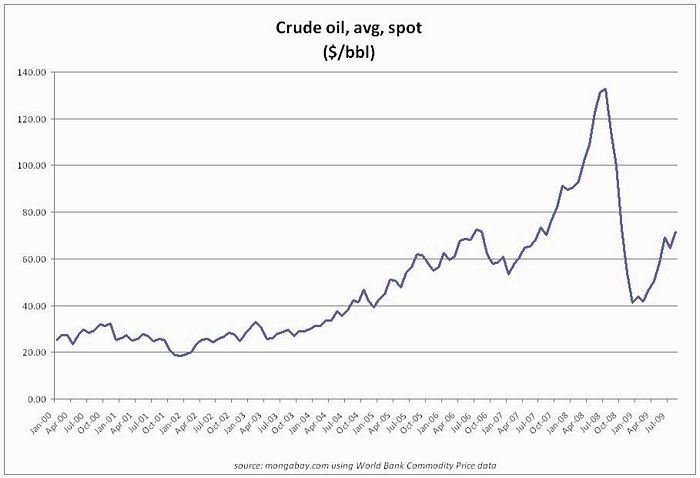

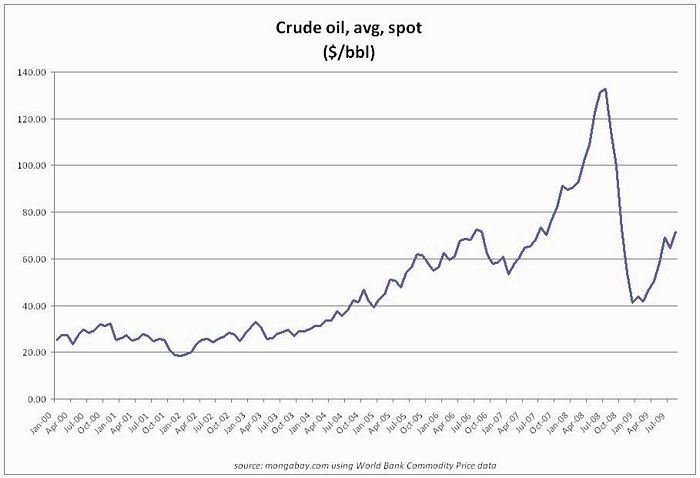

Then, put that against the longer term background of what’s been happening since 2000 (slightly older data here, via Mongabay, but usefully puts the BBC graph above in context):

As the second graph shows, today’s level of just under $80 per barrel already brings us back to where we were in around July 2007 – and that’s during a still shaky recovery from what’s generally agreed to have been the worst global recession since the early 1930s.

This is a striking rebound in such weak economic conditions – and calls to mind the consistent warnings from the IEA over the past 18 months that the collapse in investment in new supply during the financial crisis and subsequent downturn has set the stage for a new oil price crunch as soon as recovery gets underway (not to mention the fact that IEA’s chief economist thinks we’re looking at peak oil as soon as 2020).

With the oil price headed upwards, food prices can be expected to follow – because higher oil prices make biofuels more attractive, and raise the prices of on-farm energy use, fertilisers, transportation, distribution and various other elements of our energy-intensive food supply chains.

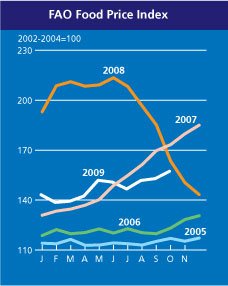

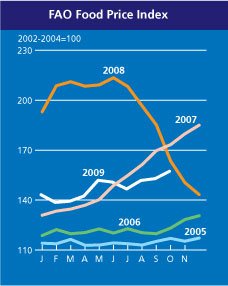

Sure enough, if we take a look at the latest FAO food price index, we find that it too has been quietly heading upwards over the last few months – and is now likewise back at where it was in July 2007. At that point, of course, the food spike was already well underway, with the tortilla riots in Mexico City that served as a wake-up call for many policymakers having come almost six months earlier.

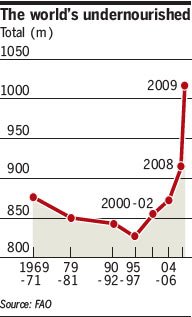

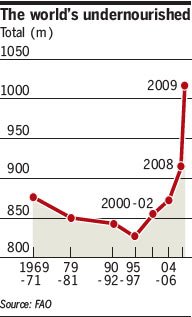

On top of this, remember the really key point that the fall in food prices that took place during the global downturn gave minimal respite to the world’s poorest people – precisely because even as prices fell, they were also getting hammered themselves by the downturn.

The starkest indication of that is in the global total of undernourished people (shown here in a graph from the FT); when you realise that we haven’t just lost the progress of the last few years, but are in far worse shape that at any time since the last 60s, you start to see just what a catastrophe the combination of food / fuel price spike followed by global downturn has been for development:

As I’ve argued in numerous previous posts, we were never out of the woods on the food / fuel pincer movement; it was the collapse in prices following the credit crunch that was the blip, not the price spike that preceded it. And what’s most frustrating now is the extent to which policymakers have frittered away the chance we had to get onto a more secure footing.

(more…)