I’ve said before that the easing of oil and food prices that followed the credit crunch and the global downturn gave policymakers a window of opportunity to take preventive action on scarcity issues. Now, alas, I think that window is starting to close – without their having done much about it.

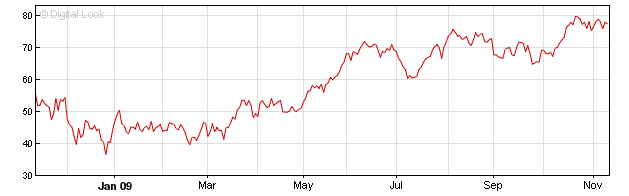

To see why, first take a look at what the oil price has been doing over the last year (Brent crude futures, $/barrel; h/t BBC):

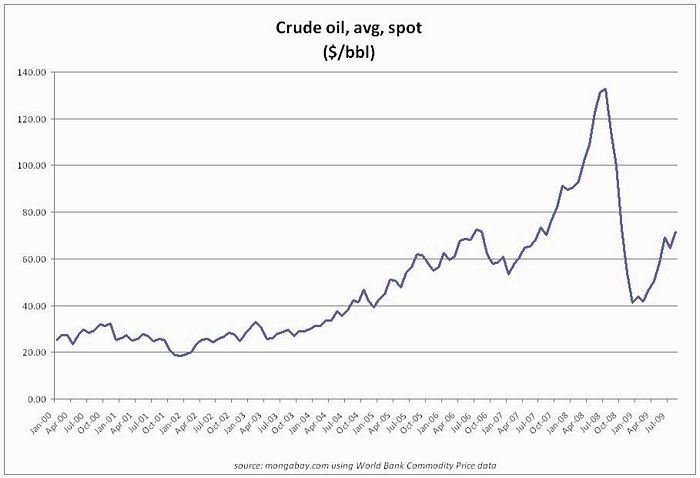

Then, put that against the longer term background of what’s been happening since 2000 (slightly older data here, via Mongabay, but usefully puts the BBC graph above in context):

As the second graph shows, today’s level of just under $80 per barrel already brings us back to where we were in around July 2007 – and that’s during a still shaky recovery from what’s generally agreed to have been the worst global recession since the early 1930s.

This is a striking rebound in such weak economic conditions – and calls to mind the consistent warnings from the IEA over the past 18 months that the collapse in investment in new supply during the financial crisis and subsequent downturn has set the stage for a new oil price crunch as soon as recovery gets underway (not to mention the fact that IEA’s chief economist thinks we’re looking at peak oil as soon as 2020).

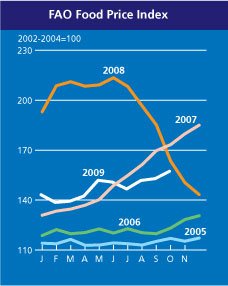

With the oil price headed upwards, food prices can be expected to follow – because higher oil prices make biofuels more attractive, and raise the prices of on-farm energy use, fertilisers, transportation, distribution and various other elements of our energy-intensive food supply chains.

Sure enough, if we take a look at the latest FAO food price index, we find that it too has been quietly heading upwards over the last few months – and is now likewise back at where it was in July 2007. At that point, of course, the food spike was already well underway, with the tortilla riots in Mexico City that served as a wake-up call for many policymakers having come almost six months earlier.

On top of this, remember the really key point that the fall in food prices that took place during the global downturn gave minimal respite to the world’s poorest people – precisely because even as prices fell, they were also getting hammered themselves by the downturn.

The starkest indication of that is in the global total of undernourished people (shown here in a graph from the FT); when you realise that we haven’t just lost the progress of the last few years, but are in far worse shape that at any time since the last 60s, you start to see just what a catastrophe the combination of food / fuel price spike followed by global downturn has been for development:

As I’ve argued in numerous previous posts, we were never out of the woods on the food / fuel pincer movement; it was the collapse in prices following the credit crunch that was the blip, not the price spike that preceded it. And what’s most frustrating now is the extent to which policymakers have frittered away the chance we had to get onto a more secure footing.

Admittedly, they committed $20bn over three years for agriculture and food security at this year’s G8 in L’Aquila (although as a friend at the ONE campaign reminded me yesterday, even that cash isn’t new or additional). But what they’ve absolutely failed to do is recognise the fact that a great deal of what we have to do is at the transboundary level as well as on the ground in developing countries. For example:

– They haven’t taken advantage of lower food prices to invest massively in a new multilateral emergency food stock. Nor have they tried to agree new WTO trade rules to prevent sudden export restrictions – something which NAFTA did years ago, and which could have been done separately from the ailing Doha trade round.

– OECD countries haven’t faced up in any way to the massive contribution their biofuel support policies made to the food price spike: take a look at the US State Dept’s shiny new food security consultation document and see if you can find the words “biofuel” or “ethanol”.

– No-one’s set any serious analytical work in train to figure out exactly how a pretty much permanent move to triple digit oil prices would affect food prices – e.g. whether the biggest pinch point will come in fertiliser or in maritime trade costs, or in which crops will be most affected.

– And hardly any policymakers are yet willing to talk about the fact that the world’s middle classes – that’s you and me – are going to have to make some pretty significant changes to our diets if we don’t want prices of staple foods to lurch out of reach of the world’s poorest (that’s significant spelled l-e-s-s m-e-a-t).

Now, on top of all of that, it looks like policymakers are also in the process of fudging the one policy process that could manage oil scarcity and climate change at the same time: the Copenhagen talks on the UNFCCC post-2012 commitment period.

The problem, of course, is that once prices for oil and food rise beyond a certain level, we all go back into kneejerk / panic mode – and try talking about the need for cooperative long term frameworks then. Sigh. #Fail.

Update #1: the FT’s Alphaville blog notes that long-dated oil contracts are now trading at $100 / barrel, and that Goldman Sachs predict corn (as well as oil) will head skyward too:

Despite the large expected harvest, we continue to anticipate a decline in US and global stocks/usage from already low levels primarily driven by rising biofuel demand. Combined with our constructive views on energy, we believe that risks to our corn forecasts are skewed to the upside.

Update #2: the Guardian has an exclusive from an unnamed “senior official” at the International Energy Agency, who says that peak oil is already here:

“The IEA in 2005 was predicting oil supplies could rise as high as 120m barrels a day by 2030 although it was forced to reduce this gradually to 116m and then 105m last year,” said the IEA source, who was unwilling to be identified for fear of reprisals inside the industry. “The 120m figure always was nonsense but even today’s number is much higher than can be justified and the IEA knows this.

“Many inside the organisation believe that maintaining oil supplies at even 90m to 95m barrels a day would be impossible but there are fears that panic could spread on the financial markets if the figures were brought down further. And the Americans fear the end of oil supremacy because it would threaten their power over access to oil resources,” he added.

Alphaville notes that the report has created “quite a stir in the oil market” today, and gives some credibility to the idea that IEA should have been massaging the numbers.

Update #3: transpires that only $3 billion of the $20 bilion G8 food security pledge is new money, according to Avaaz, who are (justly) furious about it – sign their petition ahead of FAO’s food summit here. And while you’re at it, WFP really need your help too…