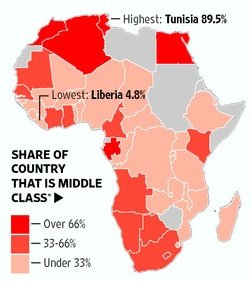

Yes says a new report from the African Development Bank which says one in three (34%) or 313m of Africa’s nearly 1bn people are now middle class (living on $2-$20/day) – a jump from 27% and about 200m in size in 2000 – after several decades without much change.

A similar report by the Asian Development Bank last year found something similar in the data, noting more than half (56%) of people in developing Asia live at the $2-$20/day level (all of this is PPP US$ by the way).

This is all good news. However, is someone living on just over $2/day ‘middle class’? $2 is the average poverty line for developing countries meaning you’re poor or middle class but what about in between? Or is there a different group altogether – those who voted for Lula in Brazil or took to the streets in the Middle East?

The Africa report notes: 62% live under $2/day and 34% of people live on $2-$20/day (of which two-thirds of these live in the $2-$4/day range or are in ‘the floating class’ in the report) and 5% live on more than $20/day.

Interestingly, Tunisia and Egypt were high up in the countries in Africa by % citizens in the middle class of $4-$20/day and also top for fewest poor people under $1.25/day tho both have surprisingly high non-monetary poverty).

Does this mean the middle classes are likely to speed up development by pushing harder for political and economic change as Foreign Policy argued?

Nancy Birdsall at CGD and myself have been working on a new idea – that there is a new group emerging in many developing countries that ought to be called the “catalytic class’ – a group that is not as secure or well-off as the Western middle class but not poor either.

Our theory is that once this group is big enough in developing countries (in population or economic or tax revenue size) it catalyzes (thus its name) internally driven, self-sustaining, political and economic pressure — from the bottom up — for better governance and economic reform. For that reason, the interests of this class coincide with the interests of the poor.

Does such a group exist? If so are they really catalytic? And what might donors do to support the emergence and expansion of such a class? And does this all sound way too political for donors?

We originally floated this idea of the ‘catalytic classes’ in a CGD wonkcast, and a CGD blog.

On CGD’s site one anonymous commenter hit on some more questions:

How does the catalytic process start? Can we identify the tipping points (and predict them)? What are the enabling conditions for such transformations? Are there ways to support/accelerate the emergence of the middle or catalytic class?

The idea also caught the attention of both Doug Saunders in Canada’s Globe and Mail who did a piece on the idea and Martin Ravallion, at the World Bank who posted a reply at the CGD site.

There was also an interesting set of exchanges between two bloggers: Aid Thoughts (and a later post) and the Principled Agent (and a later post).

The catalytic class idea seems to be somewhat malleable.

Aid Thoughts suggested in the first post we were repackaging Marx or the ‘capitalist class’ – ‘a clever rebranding ploy to sanitise capitalism for the leftist aid and development crowd’. In a longer post they went into considerably more detail noting how we don’t quite mean the ‘capitalist class’, meaning those with capital to invest per as the catalytic class might include professionals who don’t necessarily have savings to invest. And moreover markets can be effectively closed and dominated by elites.

Nor do we quite mean only the ‘entrepreneurial class’ – as the Principled Agent – linked the catalytic class to – though they were spot on with – ‘a group with a new set of public interests to compete with those of the existing elite’.

So, what do we actually mean by the catalytic classes?

There is a wealth of work on the middle classes – variously defined (see for example: Ravallion and Banerjee and Duflo, Milanovic, one of yours truly, the Asian Development Bank, and soon Francisco Ferreira and a group of economists in the Latin America and Caribbean region of the World Bank).

There are at least five reasons why the middle class (variously defined) might matter for poverty reduction. First, as small business owners their potential to hire employees. Second, their higher disposable income, a share of which could be saved and invested domestically. Third, their higher demand has potential to drive economic growth and attracts private investment. Fourth, they invest heavily in the human capital of their children creating a larger pool of skilled labour. And fifth, they’re more likely to hold the government accountable for decisions and for the financing and delivery of good public services – including for example decent schools.

In terms of hard empirical evidence, Easterly finds empirical evidence linking the middle classes and economic growth and Sridharan outlines the role of the Indian middle class in promoting reform. Ravallion too provides evidence of empirically links a middle class to growth and poverty reduction. He notes,

Countries starting out with a small middle class — judged by developing country [meaning $2-$13/day per person] rather than Western standards [ie much higher income per person — face a handicap in promoting growth and poverty reduction.

This means – taking this definition of poor and middle class (there is no in-between) – at any given mean consumption, the countries with lower poverty will have a large middle class and see higher subsequent rates of both growth and poverty reduction.

This is based on the middle class as those living on $2-$13/day, respectively the average poverty line in developing countries and the US poverty line (Ravallion). So you’re either poor (under $2/day), middle ($2-$13/day) or rich (more than $13/day).

In the middle class work there are a range of definitions – some relative – the middle class as the middle 60% of consumption expenditure (Easterly) and some absolute – the middle classes as Ravallion’s $2-$13 or those living on $2-4 or $6-8 (Banerjee and Duflo); or those living on $10-$100 – aka a global middle class (Kharas) as well as combinations (Birdsall).

The ‘catalytic classes’ are though not the ‘middle classes’.

The catalytic class is neither the poor, (ie those living on less than $1.25 or $2/day PPP) nor the ‘non poor but vulnerable’ ($2.50-$5?), nor those above $50 who we argue are the upper middle classes or elite). That leaves something in-between, say $5-$25/day?

More fundamentally, it is important to understand what is inferred by the concept of a ‘catalytic class’ (or ‘middle class’) in order to best identify the attributes that should be used to define it.

Importantly, the definition of the middle class must be clear about the extent to which the middle class ‘starts’ at the point where poverty ‘ends’ or whether there is an implicit distance between the characteristics of the poor and the middle class that would suggest a rather clearer demarcation.

Although for empirical work to begin we need a definition that is consumption based there may be more important questions to probe first: At what point does saving start? At what point does consumption of non-essentials start? (e.g. cell phone ownership?)

As Banerjee and Duflo point out, the middle classes are:

– likely to be less connected to agriculture;

– more likely to be engaged in small business activities;

– benefit from formal sector employment – more secure employment than the poor – with a weekly or monthly salary, which enables them to adopt a longer-term perspective towards their finances.

However, in contrast to the rather idealised image of the middle class as ‘risk-taking entrepreneurs’, Banerjee and Duflo highlight empirical evidence showing that many businesses operate at low profits or fail to experience significant growth.

The catalytic class, however, might be more like $5 – $25 or something closer to the classic working class plus small business owners and teachers/maybe nurses, excluding doctors, lawyers and medium business owners who can walk into a bank and get a mortgage (ie $50/day would be too high). The catalytic class are more secure than the poor and vulnerable but less secure than “middle” as a group.

If the key issue is not consumption/income per say (which is a proxy) but ‘a group with a new set of public interests to compete with those of the existing elite’ – then identification is about those whose economic interests are served not by the status quo but by progressive political and economic change.

As Doug Saunders noted in the Globe and Mail piece –

The catalytic class (a) has an interest in accountability because they pay more taxes; (b) probably don’t work for the state and thus don’t see their loyalty and interests tied to the status quo; (c) have parents who led quite different consumption lifestyles to them; (d) probably have internet (café) access and cell phones; (e) want are ‘open business conditions, fair and honourable contracts, and a route to employment unclotted by corruption’.

In short, the catalytic classes might be as follows:

- Economically: Secure but not absolutely secure – eg regular income from work but little or no income from assets;

- Politically: aspirational – want the elite to also play by the rules– they’re fed up with corruption;

- Socially: connected – have a cellphone (or Facebook or Twitter account?) so they are connected in order to be somehow catalytic and may self-identify as working class or (lower) middle class.

Is there really an idea here?

What if donors focused on supporting the emergence/expansion of this group?

(or what if aid hinders the growth of such groups?)

Ideas, comments, rants posted below please…