by Alex Evans | Nov 11, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global Dashboard

I’ve said before that the easing of oil and food prices that followed the credit crunch and the global downturn gave policymakers a window of opportunity to take preventive action on scarcity issues. Now, alas, I think that window is starting to close – without their having done much about it.

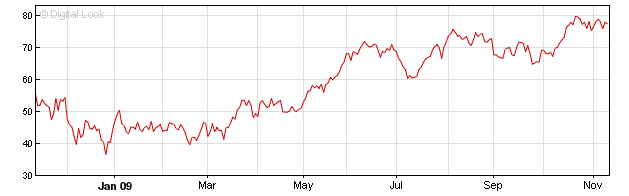

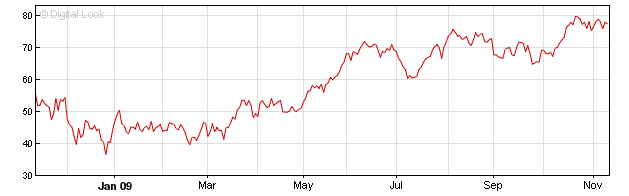

To see why, first take a look at what the oil price has been doing over the last year (Brent crude futures, $/barrel; h/t BBC):

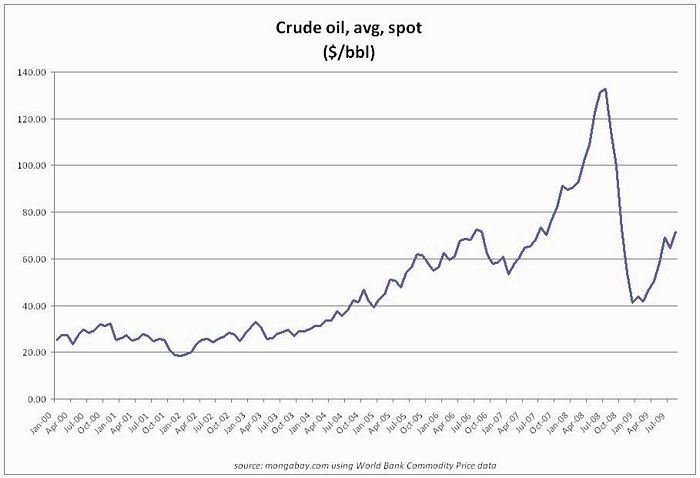

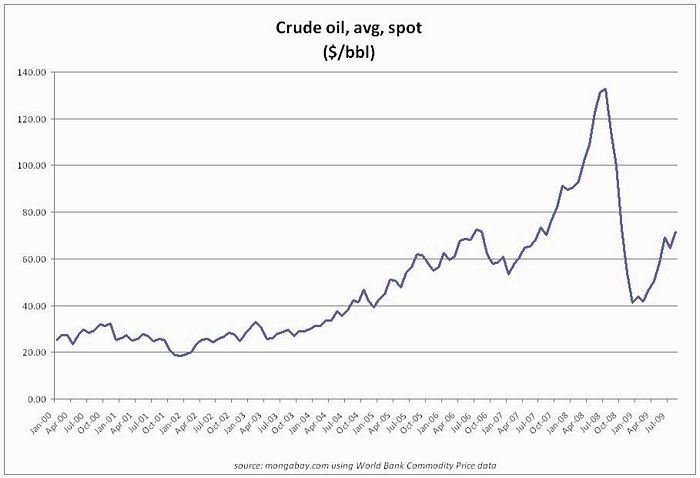

Then, put that against the longer term background of what’s been happening since 2000 (slightly older data here, via Mongabay, but usefully puts the BBC graph above in context):

As the second graph shows, today’s level of just under $80 per barrel already brings us back to where we were in around July 2007 – and that’s during a still shaky recovery from what’s generally agreed to have been the worst global recession since the early 1930s.

This is a striking rebound in such weak economic conditions – and calls to mind the consistent warnings from the IEA over the past 18 months that the collapse in investment in new supply during the financial crisis and subsequent downturn has set the stage for a new oil price crunch as soon as recovery gets underway (not to mention the fact that IEA’s chief economist thinks we’re looking at peak oil as soon as 2020).

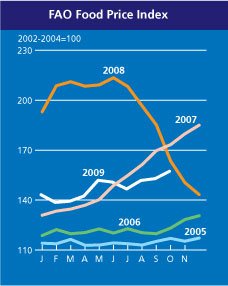

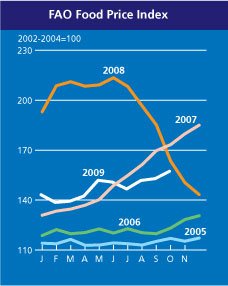

With the oil price headed upwards, food prices can be expected to follow – because higher oil prices make biofuels more attractive, and raise the prices of on-farm energy use, fertilisers, transportation, distribution and various other elements of our energy-intensive food supply chains.

Sure enough, if we take a look at the latest FAO food price index, we find that it too has been quietly heading upwards over the last few months – and is now likewise back at where it was in July 2007. At that point, of course, the food spike was already well underway, with the tortilla riots in Mexico City that served as a wake-up call for many policymakers having come almost six months earlier.

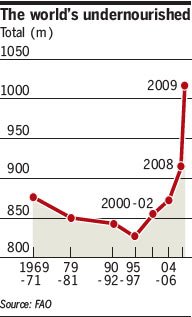

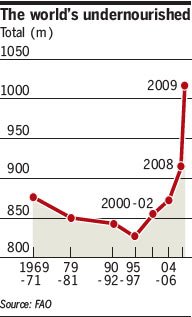

On top of this, remember the really key point that the fall in food prices that took place during the global downturn gave minimal respite to the world’s poorest people – precisely because even as prices fell, they were also getting hammered themselves by the downturn.

The starkest indication of that is in the global total of undernourished people (shown here in a graph from the FT); when you realise that we haven’t just lost the progress of the last few years, but are in far worse shape that at any time since the last 60s, you start to see just what a catastrophe the combination of food / fuel price spike followed by global downturn has been for development:

As I’ve argued in numerous previous posts, we were never out of the woods on the food / fuel pincer movement; it was the collapse in prices following the credit crunch that was the blip, not the price spike that preceded it. And what’s most frustrating now is the extent to which policymakers have frittered away the chance we had to get onto a more secure footing.

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 23, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity

If you missed it earlier in the week, the FT’s Fiona Harvey has been given a preview of the next World Energy Outlook, which the International Energy Agency will publish in November. Findings:

The recession has resulted in an unparalleled fall in greenhouse gas emissions, providing a “unique opportunity” to move the world away from highcarbon growth, an International Energy Agency study has found.

In the first big study of the impact of the recession on climate change, the IEA found that CO 2 emissions from burning fossil fuels had undergone “a significant decline” this year – further than in any year in the past 40. The fall will exceed the drop in the 1981 recession that followed the oil crisis. Falling industrial output is largely responsible for the plunge in CO 2 , but other factors have played a role, including the shelving of plans for new coal-fired power stations owing to falling demand and lack of financing.

For the first time, government policies to cut emissions have also had a significant impact. The IEA estimates that about a quarter of the reduction is the result of regulation, an “unprecedented” proportion. Three initiatives had a particular effect: Europe’s target to cut emissions by 20 per cent by 2020; US car emission standards; and China’s energy efficiency policies.

All of which brings us back to David’s prescient suggestion back in March this year that civil society “should declare 2009 the year of peak emissions and challenge the world’s governments to develop a concrete plan to ensure they are never allowed to rise again”.

Given IEA’s data, it’s clear that’s exactly what NGOs should have done. In fact, though, the TckTckTck campaign’s policy position – their only policy position, in fact – is that emissions should peak in… 2017.

Er, thanks guys. Great agenda setting there. Don’t call us – we’ll call you.

by Alex Evans | Sep 21, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, North America

With Senate climate legislation set to be introduced within a week, it’s gradually sinking in fully around the rest of the world that however loved-up we may all feel about President Obama and however welcome his commitment on climate change may be, it’s going to be the Senate that really determines the US’s negotiating position in the run-up to the Copenhagen summit. Which means, as the FT’s Edward Luce observed last week, that

Unless something miraculous happens on Capitol Hill, Mr Obama is almost certain to undershoot expectations at the climate change summit in Denmark.

While the Waxman / Markey bill that passed the House wasn’t exactly great – only a 17% emissions cut by 2020, against 2005 rather than 1990 levels, and with 85% of permits given away for free – things look even worse in the upper house:

The Senate is very unlikely to pass an equivalent bill between now and December. Against the likes of Mr Kerry and Ms Boxer are a growing caucus of centrist Democrats, from states such as Virginia, Nebraska and Michigan, which have either strong coal-based manufacturing or agricultural lobbies. Most ominously for supporters of the bill was the ascension last week of Blanche Lincoln, the embattled Democratic senator from Arkansas, to head the Senate agricultural committee. Ms Lincoln, who is facing a re-election battle next year, has described the House cap and trade bill as a “complete non-starter”.

So here’s an idea.

First, the Administration should identify a Senator who who’s firmly in the ‘no’ camp on climate change, but who also commands the respect of both sides of the House as an experienced, thoughtful statesman of manifest personal integrity. Someone like, say, Robert Byrd (D, West Virginia) – who also has the distinction, incidentally, of having co-drafted the 1997 Byrd Hagel Resolution that effectively ruled out US participation in Kyoto.

Then, President Obama should invite that Senator to be a full member of the US negotiating team at Copenhagen. (more…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 17, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global system

Excerpt from the World Bank’s just-published World Development Report 2010 (which this year takes climate change as its theme – overview pdf):

Enshrining a principle of equity in a global deal would do much to dispel such concerns and generate trust. A long-term goal of per capita emissions converging to a band could ensure that no country is locked into an unequal share of the atmospheric commons. India has recently stated that it would never exceed the average per capita emissions of high-income countries. So drastic action by high-income countries to reduce their own carbon footprint to sustainable levels is essential. This would show leadership, spur innovation, and make it feasible for all to switch to a low-carbon growth path.

Hey, did the Bank just endorse Contraction and Convergence? Not quite. As I explained a few weeks back, converging to equal per capita emission levels is not the same as converging to equal per capita emission entitlements – the difference being the small matter of whether poor countries get to benefit from emissions trading markets worth, oh, a few billion dollars. Shame the Bank missed that trick. Not so UNCTAD, on the other hand, as we saw a couple of weeks ago:

… if population size were to be given an important weight in the initial allocation of permits across countries, many developing countries would be able to sell their emission rights because they would be allotted considerably more permits than they need to cover domestically produced emissions.

Interesting coda: I was having lunch the other day with a senior official from an international agency that shall remain nameless. I was saying I couldn’t figure out why low income countries didn’t get out there and demand quantified emission targets – allocated on the basis of immediate convergence to per capita convergence in emission entitlements. His answer: because they lack an equivalent to the OECD – i.e. a think tank that supports them as a bloc.

Back in the 1970s, he continued, UNCTAD was increasingly showing signs of fulfilling this role; but it started to get too good at it, so major donor nations deliberately scaled back its funding. All the more welcome, then, to see UNCTAD punching above its weight on the biggest development issue of the 21st century. Bravo.

(PS. You might think that the G77 performs the role of an OECD for poor countries, on climate as on other issues. But you’d be wrong, on two counts. First, there’s the point that G77 lacks a secretariat – in contrast to OECD’s small army of extremely smart people in Paris. But second and more fundamentally, there’s the point that however cohesive G77 might look like from the outside, the fact is that low and middle income countries have increasingly divergent interests on climate change.

Partly it’s a question of where climate finance goes: middle income countries want to see lots of cash being pumped into low carbon development programmes that will help them to grow and to access clean technology, whereas low income countries are far more concerned with adaptation.

But more fundamentally, it’s about the emission entitlements issue. Pretty much all low income countries have per capita emissions far below the global average – so if emission permits were shared out on an equal per capita basis, they’d be making real money. Not so most of the major emerging economies – above all China, which already has per capita emissions above the global average, and would hence be a net purchaser of permits from the get-go, whenever the convergence date might be. No surprise, then, that G77 skirts around the issue, preferring to lead on the need for developed countries to cut their own emissions and cough up more climate finance…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 14, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development

From yesterday’s Sunday Times, more news that all is not well with the Clean Development Mechanism:

The legitimacy of the $100 billion (£60 billion) carbon-trading market has been called into question after the world’s largest auditor of clean-energy projects was suspended by United Nations inspectors. SGS UK had its accreditation suspended last week after it was unable to prove its staff had properly vetted projects that were then approved for the carbon-trading scheme, or even that they were qualified to do so.

It is a source of never-ending frustration to me that this dog of a policy mechanism was ever set up. The CDM, in case you haven’t had the delight of making its acquaintance, is a mechanism that’s supposed to allow developing countries to benefit from emissions trading – without having emissions targets.

If you’re wondering how that’s supposed to work, then join the queue. This is the other kind of emissions trading, the one that isn’t cap-and-trade. It’s called baseline-and-credit. What happens is that you look at (say) a factory where you’re about to install spanking new energy efficiency equipment. The idea is that you get issued with emission permits adding up to the level of emissions you’re saving by installing said technology. The problem, though, is that in order to do that, someone has to work out what the emissions would have been without it. And who the hell knows – really?

Back when the government set up the UK Emissions Trading Scheme in 2001 / 2002 (before it was superseded by the EUETS), I spent four surreal months as an official seconded in to Defra – where I was in charge of developing the baseline-and-credit part of the Scheme. It was abundantly clear that it wouldn’t result in real emissions reductions. But companies loved it – as well they might. And as for the consultants charged with designing and accrediting the projects: it was Christmas.

Now, with the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), it’s all gone global – and the same basic design problems are still, unavoidably, built in. So who has an incentive to say that the emperor wears no clothes?

Not developed country governments: they love the fact that it helps them to achieve their emissions targets cheaply (as you can see from the fact that a fifth of EUETS permits are from the CDM, or from the huge reliance on the CDM built into Waxman-Markey in the US). Not developing country governments: China and a couple of others are making money out of it, and the gripe you hear from the rest of them is not that the system is bust, but that they’re not getting a piece of the action. And certainly not the UNFCCC Secretariat (who are supposed to be impartial in all this): their little secret is that a levy on CDM transactions funds a lot of of jobs at their HQ in Bonn.

Which might leave you wondering why the NGOs don’t make more of a fuss. Alas, it’s the same old story: their long-standing inability to decide what to think about the thorny issue of developing country participation in climate mitigation. Hamstrung by a rigid interpretation of what constitutes ‘equity’ for developing countries, none of them are willing to touch the question of quantified emission targets for poor nations. With targets out of the picture, they need some alternative storyline on how developing countries are supposed to reduce emissions and get access to clean technology – and so they end up cheerleading for the CDM, and persisting in the fiction that a few tweaks will be enough to resolve the fundamental design faults with the scheme.

So with no-one out there calling time on the CDM, Copenhagen will doubtless agree another ten years for this broken mechanism that delivers neither real emissions reductions nor real finance for development.

The tragedy here is that all the while, a far better solution to these challenges has been staring us in the face: get all countries involved in quantified targets, and deal with the equity issue by sharing them out on an equal per capita basis. Presto: massive new source of finance for development, plus safely stabilised climate. But the longer we wait to do this, the more of a safe ’emissions budget’ gets used up – and the less remains to be shared with developing countries when a worsening climate means it’s no longer avoidable for them to take on targets.

The CDM represents a collective unwillingness to face up to difficult issues in the hope that they’ll get easier with time. Alas, the opposite is the case.