by Ryan Gawn | Sep 27, 2017 | Global Dashboard, Global system, Influence and networks, Off topic

Ryan Gawn looks at a new report on how emerging technology can help the United Nations reform

The September gathering of world leaders has  come and gone, and UN Secretary-General Guterres is now back at his desk. Whilst his attention is likely to be focussed on headlines coming from North Korea, Syria and Myanmar, he is also battling to advance reform of the UN system. As with any large bureaucracy (not least one which has to manage the expectations of 193 member states) the ever present reform agenda can quickly become all-consuming for a Secretary-General. This leaves very little time to look outside the UN system and its political machinations, and identify challenges and opportunities on the horizon. Such as emerging technologies.

come and gone, and UN Secretary-General Guterres is now back at his desk. Whilst his attention is likely to be focussed on headlines coming from North Korea, Syria and Myanmar, he is also battling to advance reform of the UN system. As with any large bureaucracy (not least one which has to manage the expectations of 193 member states) the ever present reform agenda can quickly become all-consuming for a Secretary-General. This leaves very little time to look outside the UN system and its political machinations, and identify challenges and opportunities on the horizon. Such as emerging technologies.

Big Questions

The pace of technological change brings with it extraordinary opportunities and challenges for the UN and its work. A new report looks ahead, shines a spotlight on the future, and makes some practical recommendations for the Secretary-General on how the UN can respond. Authored by former UK Ambassador Tom Fletcher and supported by the Emirates Diplomatic Academy, New York University and the Makhzoumi Foundation, “United Networks – How Technology can help the United Nations Meet the Challenges of the 21st Century” sets out some big questions for the future of the UN:

“How can the UN adapt its methods to the Networked Age without compromising its values? How can technology increase UN effectiveness and efficiency, build public trust, mobilise opinion and action, and weaponise compassion? How to make the sum of the parts more able to deliver on the goals set out so powerfully in the UN Charter seven decades ago?”

20 recommendations

As part of a team of expert contributors (including young people, tech gurus and activists), I led on the public engagement and political issues which emerging technologies can bring. Consulting with innovation leaders, governments, tech companies and NGOs, we were astounded by the many examples where existing technology is already being used to tackle many of the problems which the UN seeks to solve. It also makes 20 recommendations for the Secretary-General to consider, proposing international agreements (e.g. a Geneva convention on state actions in cyberspace, a universal declaration of digital rights, a single digital identity), equipping the UN with the right skills and resources (e.g. a Deputy Secretary-General for the Future, a global crowdfunding platform to fund humanitarian work, machine learning & data modelling to predict migrant and refugee flows, harnessing artificial intelligence and big data to make better decisions), and using the UN’s status to enhance citizenship and reduce extremism (e.g. diplo-bots to reduce online extremism, enhancing internet access and reducing the digital divide, a digital global curriculum).

Reputation & public engagement

A critical factor in the reform agenda  and the ability of the UN to effectively innovate and harness technology is its reputation and public engagement – the UN is nothing without public, business, civil society and member state support. Considered by many to be the closest humanity has to world government, many of the criticisms of the UN are borne from the high expectations citizens have of the organisation, particularly regarding transparency, accountability, legitimacy, demonstrating impact, and regaining trust. And so in engaging with its audiences, the UN faces a profound dichotomy in managing expectations – how to balance the aspirational and moral value of the UN with the realist politics of a multilateral organisation within a cumbersome bureaucracy. UK Prime Minister Theresa May highlighted this very issue in her recent address to the General Assembly: “…throughout its history the UN has suffered from a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the nobility of its purposes and the effectiveness of its delivery. When the need for multilateral action has never been greater the shortcomings of the UN and its institutions risk undermining the confidence of states as members and donors.”

and the ability of the UN to effectively innovate and harness technology is its reputation and public engagement – the UN is nothing without public, business, civil society and member state support. Considered by many to be the closest humanity has to world government, many of the criticisms of the UN are borne from the high expectations citizens have of the organisation, particularly regarding transparency, accountability, legitimacy, demonstrating impact, and regaining trust. And so in engaging with its audiences, the UN faces a profound dichotomy in managing expectations – how to balance the aspirational and moral value of the UN with the realist politics of a multilateral organisation within a cumbersome bureaucracy. UK Prime Minister Theresa May highlighted this very issue in her recent address to the General Assembly: “…throughout its history the UN has suffered from a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the nobility of its purposes and the effectiveness of its delivery. When the need for multilateral action has never been greater the shortcomings of the UN and its institutions risk undermining the confidence of states as members and donors.”

The report presents this expectation / impact gap with 21st century digital twist – emerging technologies in public engagement will only exacerbate citizens’ demands for information, evidence of impact, authentic engagement, and compelling narratives on the value the UN brings. This is coupled with the rapid pace of technological change, media consumption and marketing shifts (voice, mobile, AR & VR), changes in attention spans, information expectations and social media echo chambers.

Nevertheless, emerging technologies can also help solve some of these challenges. The report provides some practical recommendations in this area, with a common thread involving harnessing technologies to provide both wider and deeper engagement – empowering audiences to both input into and communicate the UN’s work and mission. Examples include a digital first strategy, stronger authentic social media engagement by officials, a more transparent process for S-G selection, crowd sourcing of solutions, digital platforms for policy debate, chat-bots to enhance audience engagement and democratisation of user generated content to empower citizens, activists and campaigners in the digital space.”

More opportunities than challenges

An inherently optimistic report, it does not see  emerging technology as a panacea to solve all the UN’s many challenges. It won’t always be as empowering and enlightening as Silicon Valley tech gods may opine, and will inherently be somewhat limited by our mere human use (or misuse) of it. Nevertheless, it recognises that there are opportunities, and that the UN must innovate with urgency or face a slow slide into under resourced decline and irrelevance. More importantly, it highlights the need for the UN to be ahead of the curve – looking outwards, partnering and engaging, and setting the agenda – just as it has already achieved in many other areas. A stronger reputation and public engagement can only help in making this aspiration a reality. As Fletcher concludes:

emerging technology as a panacea to solve all the UN’s many challenges. It won’t always be as empowering and enlightening as Silicon Valley tech gods may opine, and will inherently be somewhat limited by our mere human use (or misuse) of it. Nevertheless, it recognises that there are opportunities, and that the UN must innovate with urgency or face a slow slide into under resourced decline and irrelevance. More importantly, it highlights the need for the UN to be ahead of the curve – looking outwards, partnering and engaging, and setting the agenda – just as it has already achieved in many other areas. A stronger reputation and public engagement can only help in making this aspiration a reality. As Fletcher concludes:

“If digital information is the 21st century’s most precious resource, the battle for it will be as contested as the battles for fire, axes, iron or steel. Between libertarians and control freaks. Between people who want to share ideas and those who want to exploit them. Between those who want more transparency, including many individuals, companies, and governments. And those who want more secrecy. Between old and new sources of power.”

Update – 27/09/17: United Nations opens new centre in Netherlands to monitor artificial intelligence and predict possible threats

by Ryan Gawn | Jul 22, 2015 | Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Global system, Influence and networks, UK

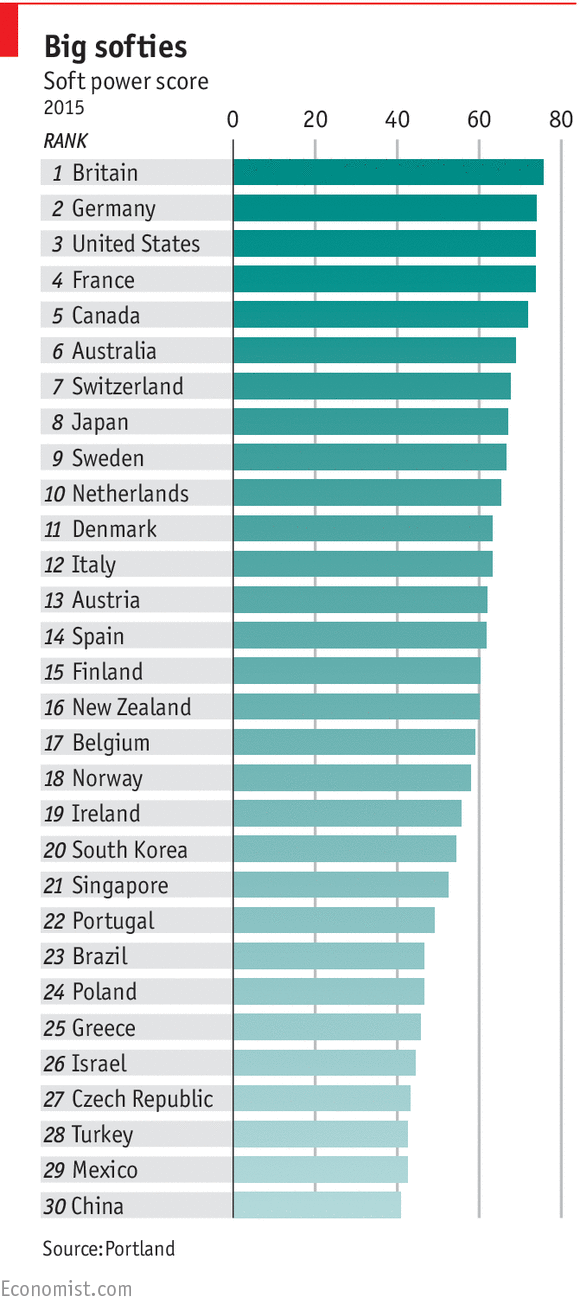

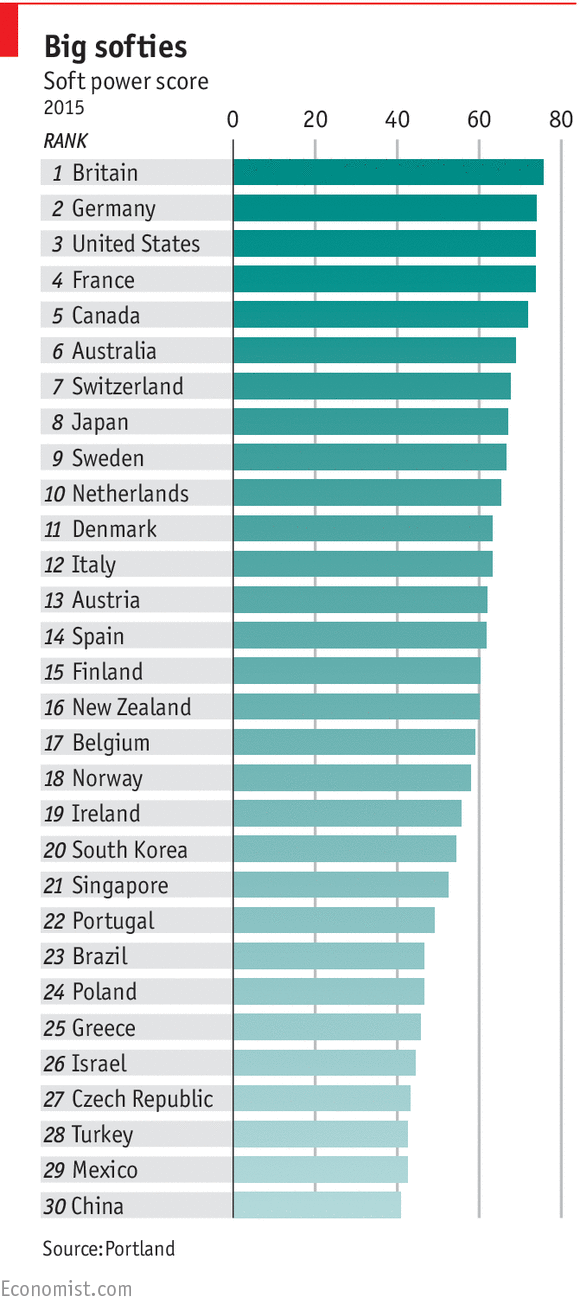

Last week saw the launch of a new global #softpower report, ranking the UK at the top of a 30-country index. Compiled by Portland, Facebook and ComRes, the report is described by Joseph Nye (who coined the term in 1990) as “the clearest picture to date of global soft power”, and has ranked countries in six categories (enterprise, culture, digital, government, engagement, education).

There are quite a few of these indices around now, with varying methodologies – nevertheless, this is the first to incorporate data on government’s online impact and international polling. Who’s at the top of the tables isn’t really surprising (the top 5 countries – UK, Germany, US, France, Canada – are identical to the top 5 in the Anholt-GFK Roper Nation Brand Index, but with a slight reordering of ranking). The US, Switzerland and France topped the specific categories, and although not first place in any of the categories, the UK ranked highest overall, reflecting its strength in culture, education, engagement & digital. More on the UK later.

What is really surprising is that China finishes last. Following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets (such as the Xinhua news agency, aid/ development projects), at a time when others have been paring back their ambitions. Nevertheless, the impact of this investment isn’t borne out in the results, likely hindered by negative perceptions of China’s foreign policy, questionable domestic policies and a weakness in digital diplomacy. China came out strongest in the culture, likely reflective of the many Confucius Institutes dotted around the globe.

There are a few other interesting nuggets:

· Broader power trends are increasing the need for soft power – 3 factors driving global affairs away from bilateral diplomacy and hierarchies and toward a much more complex world of networks:

1. Rapid diffusion of power between states

2. Erosion of traditional power structures

3. Mass urbanisation

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Jun 14, 2010 | Climate and resource scarcity, Influence and networks

One of the many strands of discussion at a Ditchley Foundation conference on climate change last week was the vexed question of how public opinion shapes the political space open to leaders on climate. There were many furrowed brows on this, not least given that the polling numbers on climate change are all heading the wrong way, all over the world – perhaps unsurprisingly, given the combination of the recession and media coverage of ‘climategate’.

My own take on this is that when we think about public opinion in the climate context, we’re a bit too fast to look at it through the lens of NGOs and the media – both of which had, I think, a terrible summit at Copenhagen.

Take NGOs first. For the most part, they concentrated on highly technical issues, as they have throughout the past decade – acting, in other words, like negotiators despite not having any bargaining chips. When they tried to look up a bit, and set an overall agenda, it was so vague as to be meaningless (“ambitious, fair, binding” – more on that here). Finally, as the summit fell apart, they retreated to their habitual comfort zone of arguing that it was all the fault of the US and EU, who had been unforgivably horrid to poor old China. (See Mark Lynas for a blistering critique of that view.)

Then, of course, there’s the feral nature of the 24/7 news media, which cheerfully overlooks its own agenda-setting role even as it peddles its sensationalised stories of stitch-ups, scandals and show-downs.

The Guardian’s John Vidal deserves singling out for an especially dishonourable mention here. Just two days in to Copenhagen, he ran a breathless piece saying that Copenhagen was “in disarray” following the leak of a draft agreement that “would hand more power to rich nations”. Never mind that the content of his piece was highly questionable (as we pointed out on GD at the time). The effect was to poison the atmosphere just as the summit began – leading the Indian environment minister to say in April this year that the summit had been “destroyed from the start” by the Guardian leak. Nice one, John!

So given that it would appear to be unwise to expect either NGOs or the media to help shape public opinion more constructively, what’s left? One suggestion at the conference was a bigger role for faith leaders – who are indeed getting steadily more active on climate.

But my hunch is that it’s social networking technologies that are the key opinion formers to watch.

We’ve seen how breathtakingly fast they are at aggregating information – as during the Mumbai attacks, for instance, where Twitter was consistently 60-90 minutes ahead of the news media. We’ve seen how they aggregate opinion as well as information – which can of course be as much of a curse as a blessing. And we’ve seen how they can organise action – not just protest, but also more proactive policy solutions.

But what we haven’t seen, yet, is how all these elements could combine in the face of stronger climate impacts – not just an extreme weather event, but an impact that could really trigger awareness of the potential for irreversible shifts. Strikes me that social networking technologies would be a highly unpredictable and interesting wild card in such circumstances – and potentially rather more useful than either NGOs or the media.

by David Steven | May 7, 2010 | UK

Given the chaos in voting during the General Election, here’s how to do it better, while making elections a more televisual, social media-friendly experience.

As I argued in October:

Some thoughts on elections, which are – as things stand – the epitome of everything people hate about the public sector (inconvenient, confusing, dingy, etc). With a little redesign, we could make them so much more entertaining, user friendly, and festive: fit for the modern media age.

Consider. We live in the age of live. The online revolution has destroyed many business models, but it is driving the value of one-off events through the roof. Rock stars release albums to promote their live shows (ten years ago, it was the other way round). Sky’s business model is based on the capture of live sport, especially football.

Master manipulator, Derren Brown, understands this better than anyone. His recent series was structured deliberately as a series of events – designed to provoke and gel together a stream of frenzied media and online coverage.

To be sure, a British general election is gripping, but almost inspite of itself. We’ll soon be having the first British general election of the Twitter era, but as always the results will dribble in the middle of the night (thus ‘were you still up for Portillo?’).

That didn’t matter a jot in the print era – and television has learned to make the most of the bad timing. But it’s surely wrong for the new media age. When we next go the polls, most of the British public will be asleep when we get to the climax.

My suggestion:

- A Democracy Day, either every two and a half years – with a general election in June and a mid-term in November, or every two years, moving British politics onto a fixed four-year cycle.

- All elections – Westminster, devolved government, councils, European parliament, referenda, etc – will be held on one of these days (by-elections would be the only exception).

- Voting would be as easy as possible, with polls open throughout the week before, and voting could be made compulsory (with a ‘none of the above’ option, of course).

- Democracy Day – a Monday – would be a public holiday – with polls closing at 6 o’clock.

- Sunderland would then do its usual party trick and gets its result out within the hour. The rest of the action would then unfold across prime time; even in the closest years, the result would be clear before the nation went to bed.

- The TV audience would be huge; Twitter and its ilk would go berserk (think of all the local coverage from counts); while election parties and victory rallies could happen at a sensible time.

Some advantages:

– Fixed terms: a predictable, harmonised electoral cycle, with a clear rhythm for politician, bureaucrat and public.

– The creation of a consistent democratic system, even as devolution leads to confusing fragmentation.

– Economies of scale for electoral commission, political parties, media, etc, from running fewer, bigger elections.

– Opportunities to expand the role played by direct democracy in British political life, by running more referenda, elections to quangos and other public bodies, etc.

– More time to vote – which seems pretty important today.

– An unmissable media event.

Details:

– The June election might need to float slightly, depending on the date set for European parliamentary elections (though hopefully Europe will settle). But – before Eurosceptics start frothing at the mouth – there are great advantages to having national and European elections in the same cycle. The party in power in Westminster would also lead in Brussels, providing a much more consistent voice for the British electorate in Europe, while turnout would be much much higher, ensuring a better reflection of UK opinion.

– The general election would cover the House of Commons, Europe, and the devolved administrations, plus some councillors and seats in the (new) House of Lords. The minor election would be just local government, the Lords, and any odds and sods (referenda, quangos, etc).

– In a remodelled Lords, I’d like to see elected members able to serve only a single 10 or 8-year term – staggered, so a small number of members would be elected each Democracy Day (a small enough list for people to vote for individuals, not parties).

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 4, 2010 | Influence and networks, UK

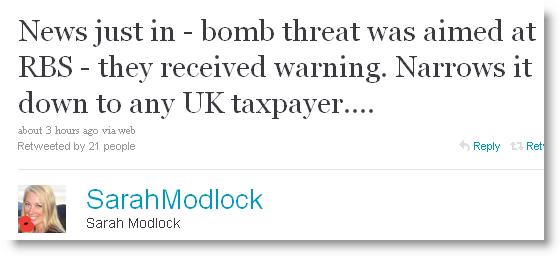

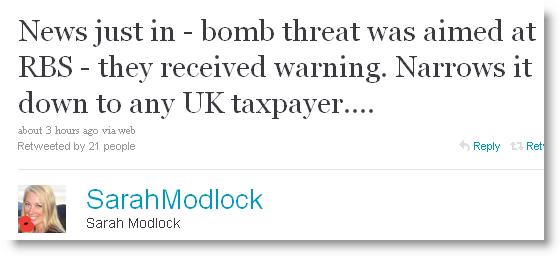

For a while today, Twitter lit up with speculation about a couple of bombs in Aldgate, East London – rumours that swirled around long after the Metropolitan Police had declared the incident a false alarm.

The scare was fuelled by tweets from those inside the security cordon, such as those from consumer affairs journalist, Sarah Modlock, who reported that there were “two IEDs, one in car, one in phone box. One dealt with and one being dealt with. Two roads reopened.”

Modlock has lots of very plausible detail, some of it from “mates” at the Royal Bank 0f Scotland, whose office she said was being targeted by the attack. “I just said what came up here as we were told – no spin,” she said, after the all-clear was given.

So… (i) Modlock is in her office desperate for information about what is happening out on the streets; (ii) she is picking up rumours and passing them on; (iii) her ‘privileged’ position within the evacuated zone gives her reports credibility – weak signals become strong ones.

These feedback loops are not new to social media. Something very similar happened when Katrina hit New Orleans and the media covered, as fact, an orgy of violence in the Superdome, where many of the city’s poorest and most disadvantaged citizens were sheltering.

Extremely graphic tales of how the poor were raping and murdering one another (30-40 bodies in the convention centre’s freezer, for example) turned out to be vastly exaggerated. Few of the reports of violence were later confirmed (though police are now known to have executed civilians).

According to Ed Bush, a public affairs official for the Louisiana National Guard, those inside the centre were hearing reports of atrocities from the media. They were then telling these stories back to journalists, creating a perfect storm of misinformation.

A lot of them had AM radios, and they would listen to news reports that talked about the dead bodies at the Superdome, and the murders in the bathrooms of the Superdome, and the babies being raped at the Superdome and it would create terrible panic. I would have to try and convince them that no, it wasn’t happening.

The Dome, of course, was characterised by information scarcity – “Cell phones didn’t work, the arena’s public address system wouldn’t run on generator power, and the law enforcement on hand was reduced to talking to the 20,000 evacuees using bullhorns and a lot of legwork.”

In contrast, Twitter (plus the rest of the social media) multiplies connections (absent a loss of power/Internet etc.). So, in a more complex emergency than today’s, can we expect denser networks, with the potential they allow for correction and multiple points of view, to provide a quicker or more tortuous route to the truth?

Update: According to the Sun:

Fake improvised explosive devices made up of artillery shell casings, mobile phones and Plasticine were spotted in the Suzuki Ignis car.

But it turned out the men, who work for a legitimate counter-terrorism firm, had just been showing them to business leaders in the Square Mile to warn of the dangers…

A police source said: “They couldn’t have picked a worse day. We will be having strong words with them over their stupidity.”

Ooops. (If true, of course. Maybe the Met could, y’know, put a statement on its website.)

come and gone, and UN Secretary-General Guterres is now back at his desk. Whilst his attention is likely to be focussed on headlines coming from North Korea, Syria and Myanmar, he is also battling to advance reform of the UN system. As with any large bureaucracy (not least one which has to manage the expectations of 193 member states) the ever present reform agenda can quickly become all-consuming for a Secretary-General. This leaves very little time to look outside the UN system and its political machinations, and identify challenges and opportunities on the horizon. Such as emerging technologies.

come and gone, and UN Secretary-General Guterres is now back at his desk. Whilst his attention is likely to be focussed on headlines coming from North Korea, Syria and Myanmar, he is also battling to advance reform of the UN system. As with any large bureaucracy (not least one which has to manage the expectations of 193 member states) the ever present reform agenda can quickly become all-consuming for a Secretary-General. This leaves very little time to look outside the UN system and its political machinations, and identify challenges and opportunities on the horizon. Such as emerging technologies. and the ability of the UN to effectively innovate and harness technology is its reputation and public engagement – the UN is nothing without public, business, civil society and member state support. Considered by many to be the closest humanity has to world government, many of the criticisms of the UN are borne from the high expectations citizens have of the organisation, particularly regarding transparency, accountability, legitimacy, demonstrating impact, and regaining trust. And so in engaging with its audiences, the UN faces a profound dichotomy in managing expectations – how to balance the aspirational and moral value of the UN with the realist politics of a multilateral organisation within a cumbersome bureaucracy. UK Prime Minister Theresa May highlighted this very issue in her recent address to the General Assembly: “…throughout its history the UN has suffered from a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the nobility of its purposes and the effectiveness of its delivery. When the need for multilateral action has never been greater the shortcomings of the UN and its institutions risk undermining the confidence of states as members and donors.”

and the ability of the UN to effectively innovate and harness technology is its reputation and public engagement – the UN is nothing without public, business, civil society and member state support. Considered by many to be the closest humanity has to world government, many of the criticisms of the UN are borne from the high expectations citizens have of the organisation, particularly regarding transparency, accountability, legitimacy, demonstrating impact, and regaining trust. And so in engaging with its audiences, the UN faces a profound dichotomy in managing expectations – how to balance the aspirational and moral value of the UN with the realist politics of a multilateral organisation within a cumbersome bureaucracy. UK Prime Minister Theresa May highlighted this very issue in her recent address to the General Assembly: “…throughout its history the UN has suffered from a seemingly unbridgeable gap between the nobility of its purposes and the effectiveness of its delivery. When the need for multilateral action has never been greater the shortcomings of the UN and its institutions risk undermining the confidence of states as members and donors.” emerging technology as a panacea to solve all the UN’s many challenges. It won’t always be as empowering and enlightening as Silicon Valley tech gods may opine, and will inherently be somewhat limited by our mere human use (or misuse) of it. Nevertheless, it recognises that there are opportunities, and that the UN must innovate with urgency or face a slow slide into under resourced decline and irrelevance. More importantly, it highlights the need for the UN to be ahead of the curve – looking outwards, partnering and engaging, and setting the agenda – just as it has already achieved in many other areas. A stronger reputation and public engagement can only help in making this aspiration a reality. As Fletcher concludes:

emerging technology as a panacea to solve all the UN’s many challenges. It won’t always be as empowering and enlightening as Silicon Valley tech gods may opine, and will inherently be somewhat limited by our mere human use (or misuse) of it. Nevertheless, it recognises that there are opportunities, and that the UN must innovate with urgency or face a slow slide into under resourced decline and irrelevance. More importantly, it highlights the need for the UN to be ahead of the curve – looking outwards, partnering and engaging, and setting the agenda – just as it has already achieved in many other areas. A stronger reputation and public engagement can only help in making this aspiration a reality. As Fletcher concludes: