by Alex Evans | Dec 13, 2009 | Articles and Publications, Reports

World Food Programme report on the state of the science on what climate change means for hunger, plus policy recommendations. Authored by IPCC Impacts Chair Martin Parry with Mark Rosengrant, Tim Wheeler and Global Dashboard’s Alex Evans (December 2009)

Download Report

by Alex Evans | Nov 11, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global Dashboard

I’ve said before that the easing of oil and food prices that followed the credit crunch and the global downturn gave policymakers a window of opportunity to take preventive action on scarcity issues. Now, alas, I think that window is starting to close – without their having done much about it.

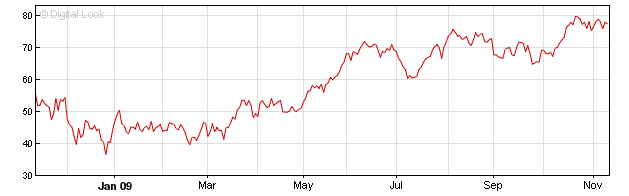

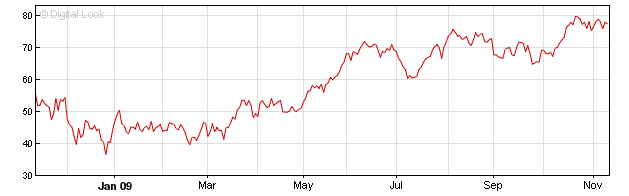

To see why, first take a look at what the oil price has been doing over the last year (Brent crude futures, $/barrel; h/t BBC):

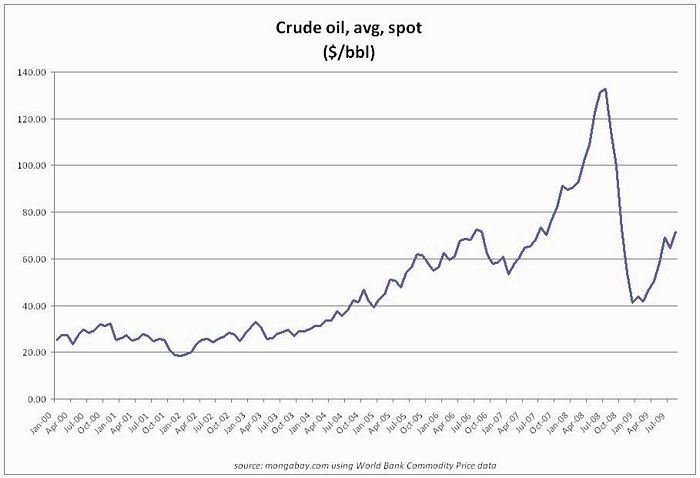

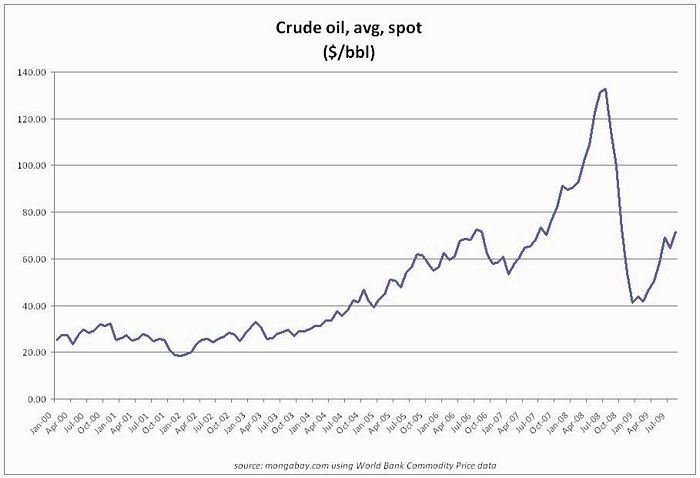

Then, put that against the longer term background of what’s been happening since 2000 (slightly older data here, via Mongabay, but usefully puts the BBC graph above in context):

As the second graph shows, today’s level of just under $80 per barrel already brings us back to where we were in around July 2007 – and that’s during a still shaky recovery from what’s generally agreed to have been the worst global recession since the early 1930s.

This is a striking rebound in such weak economic conditions – and calls to mind the consistent warnings from the IEA over the past 18 months that the collapse in investment in new supply during the financial crisis and subsequent downturn has set the stage for a new oil price crunch as soon as recovery gets underway (not to mention the fact that IEA’s chief economist thinks we’re looking at peak oil as soon as 2020).

With the oil price headed upwards, food prices can be expected to follow – because higher oil prices make biofuels more attractive, and raise the prices of on-farm energy use, fertilisers, transportation, distribution and various other elements of our energy-intensive food supply chains.

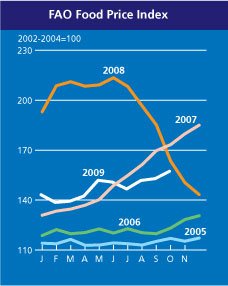

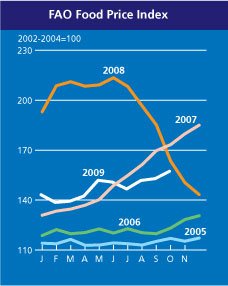

Sure enough, if we take a look at the latest FAO food price index, we find that it too has been quietly heading upwards over the last few months – and is now likewise back at where it was in July 2007. At that point, of course, the food spike was already well underway, with the tortilla riots in Mexico City that served as a wake-up call for many policymakers having come almost six months earlier.

On top of this, remember the really key point that the fall in food prices that took place during the global downturn gave minimal respite to the world’s poorest people – precisely because even as prices fell, they were also getting hammered themselves by the downturn.

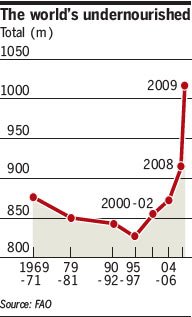

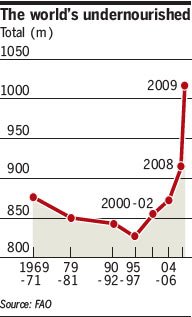

The starkest indication of that is in the global total of undernourished people (shown here in a graph from the FT); when you realise that we haven’t just lost the progress of the last few years, but are in far worse shape that at any time since the last 60s, you start to see just what a catastrophe the combination of food / fuel price spike followed by global downturn has been for development:

As I’ve argued in numerous previous posts, we were never out of the woods on the food / fuel pincer movement; it was the collapse in prices following the credit crunch that was the blip, not the price spike that preceded it. And what’s most frustrating now is the extent to which policymakers have frittered away the chance we had to get onto a more secure footing.

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 18, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global system

So what should we all be watching out for at next week’s G20 summit? Let’s start with the obvious stuff.

– Expect to hear lots about bankers’ bonuses, in particular from Brown, Merkel and Sarkozy. I can’t find it in me to give a crap about this issue, but doubtless it will command saturation media coverage all week. More substantive on the banking front will be the question of whether concrete proposals are advanced for hedge fund rules or financial supervision regulation – lots of noise here, but not much specificity so far.

– We’ll also hear lots of debate about when to wind down stimulus programs – which was a big issue at the EU’s preparatory summit (continentals more hawkish, but Brown edgier about turning the taps off). Goldman Sachs’s Jim O’Neill has an op-ed in the FT this morning arguing that while co-ordination was needed for starting the stimulus off, it’s less necessary to have co-ordinated exit strategies.

– The IMF and the World Bank have been doing good advocacy about the need not to forget about low income countries. Zoellick and Strauss-Kahn are both arguing that LICs have an external financing deficit of around $59bn this year (for comparison, that’s exactly half the 2008 global aid total). On the plus side, G20 members have actually delivered the $500bn they promised the IMF – which means the Fund can front up around a third of the total needed. Strauss-Kahn is also talking about a breakthrough on IMF governance reform. (Believe it when I see it.)

– We’ll hear a lot about climate, but it’s hard to see what deal the G20 is supposed to cut (especially with Ban Ki-moon’s heads-level climate summit in New York the same week). The story the media runs with will be all about pressure on the US to do more, following Japan’s announcement of a tougher 2020 emissions target, and the EU’s long-awaited finance package. (Still, Obama ain’t the problem – the real issue here, of course, is that things don’t look great in the US Senate.)

The issue on the agenda that I’m most interested in for next week, though, is trade. First, what – if anything – will the G20 say on protectionism? For all the warm words at the London Summit in April, it’s increasingly clear that most G20 countries are in breach of their commitments – right now most notably in the case of the US, whose new tire tariffs are disastrous. Dan Drezner’s take on this is worth reading (things are “very, very scary”) – but on the other hand, Alan Beattie thinks White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel may have a crafty and ultimately beneficial political calculus in mind.

On a related note, how intriguing to see US sherpa Mike Froman talking up Pittsburgh’s chances of tackling global economic imbalances (“we hope to reach agreement on a framework for balanced growth, for agreeing on how to address the imbalances that led to this crisis and on some process for holding each other accountable”). Not what I expected – but great, if he can pull it off. That said, I found myself wondering last night: is it conceivable that this is part of a messaging strategy to defend the tire tariffs? Hollow laughs all round if so.

Finally, the issue no-one’s talking about but everyone should be: the impending return of the food / fuel price spike. All these stories about oil companies finding new giant fields are so much straw in the wind. (So the new Jubilee field off Sierra Leone has 1.8bn barrels? Great: a whole twenty-one days’ global demand. Colour me thrilled.) The more fundamental point is about demand, which is picking up again in the non-OECD economies – and let’s remember that it’s in these countries that all the demand growth for oil will come between now and 2030.

The stage remains firmly set for a renewed oil supply (and hence price) crunch in the short term – and when that happens, food prices will go straight up too, as costs for transport, fertiliser and on-farm energy use race upwards and biofuels become even more competitive as a source of demand for crops. We’re already at a baseline of 1.04bn undernourished people (compared to 850m before the last food price spike) – do the maths. So my wish list for the G20?

- $6bn funding for WFP – now.

- Leave the trade round on hold, but agree emergency WTO rules against food export restrictions (like the ones that already exist in NAFTA).

- Build up a multilaterally managed emergency food stock – maybe part real, part virtual (see Feeding of the 9 Billion for full details).

- Commit to universal access to social protection systems by (say) 2015 – and lock the funding in place, now (only 20% of the world’s people currently have access to them – but these are the best-defence resilience mechanism for poor people facing price spikes, way better than price controls or economy-wide subsidies)

- Bring China and India into full IEA membership, so that they’re part of its emergency supply management mechanism.

- Start driving real inter-agency coherence by commissioning the most important multilateral agencies for scarcity issues – UN, Bank, Fund, OCHA, WFP, FAO, IEA – to produce a joint World Resources Outlook. We need the integrated analysis; we need the political momentum it will create.

- Ask Ban Ki-moon to set up a High Level Panel to look at the international institutional dimensions of climate, scarcity and development – covering not just the UN, but the entire international system. This is the bit of international system reform that both the 2004 and 2006 High Level Panels left for another day. Today is that day.

by Alex Evans | Sep 1, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity

Ten years of freedom for East Timor today, and a notably graceful editorial in the Jakarta Post:

Indonesia would have learned a great deal from the fatal mistakes of its 24-year occupation of the then East Timor, now Timor Leste, so it hardly needs more lessons. Well perhaps one more: a lesson on statesmanship from President José Ramos-Horta.

On the 10th anniversary of the UN-sponsored independence referendum that ended Indonesian rule, Ramos-Horta’s speech Saturday was worthy of his standing as a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, part of which read “My stated preference, as a human being, victim and head of state, is that we once and for all close the 1975-1999 chapters of our tragic experience [and] forgive those who did us harm.”

It concludes:

Timor Leste is fortunate to have truly great statesmen like Ramos-Horta and Gusmao. Statesmanship will remain in short supply among Indonesian leaders for as long as we continue to let human rights violations go unpunished. While our leaders are busy talking the talk at international forums, we are certainly not walking the human rights walk.

But in an FT interview, Ramos-Horta’s own preoccupations are focused on the future:

José Ramos Horta, the president, who shared the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end the Indonesian rule that left more than 150,000 Timorese dead, says that when a shortage of water and dependence on subsistence agriculture is added, the scale of the problems the country faces cannot be overstated.

“With this population growth and poverty, [and] increasing pressure on water and land, 20 years from now we will start killing each other over water and land,” he told the Financial Times. He has no doubt that, unless more attention is paid to rural areas, urban migration – particularly among the rapidly escalating ranks of disillusioned and unemployed youth – will be so great that it will create a “time bomb”.

by Alex Evans | Aug 26, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity

I spent yesterday morning presenting on scarcity issues – water, food, energy, land and climate security – to staff from the UN Department of Political Affairs, as part of a three day session on non-traditional security threats organised by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy.

Here’s a copy of my presentation on the kinds of institutional change we need in order to manage scarcity, which focuses particularly on reducing the vulnerability of poor people and fragile states. This draws heavily on a new report on Multilateralism and Scarcity that I’ll be publishing through the Brookings Institution later in the year.

Also presenting were Geoff Dabelko from the Woodrow Wilson Center (if you don’t subscribe to The New Security Beat, the Center’s superb blog on scarcity-security links, then you should); and Mike Hutton from the US Department of Energy’s Office for Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence (as previously documented here, one of a handful of hotspots of radical forward thinking in the US government – you can get involved, too).