by David Steven | May 11, 2010 | UK

Yesterday, I indulged in some late night speculation, wondering whether the only ‘impossible’ election outcome – the Queen being forced to send parties back to the country – might now have an outside chance of popping out of the pack.

Why consider such an outlandish possibility?

It’s important to do so, I think, because that’s the only way to make good decisions under conditions of radical uncertainty.

Look at how David Cameron’s team is said by the Telegraph to have acted even before polls closed last week:

By shortly after 7pm on Thursday, Jeremy Heywood, the Permanent Secretary at 10, Downing Street, received an extraordinary telephone call.

On the line was one of David Cameron’s closest aides, so confident of a Conservative majority that he spent the next five minutes dictating the names of every minister in the new Cameron government and the names of the civil servants who would be sacked the next day.

Even in the midst of the most unpredictable election in a generation, I suspect the Conservatives were far too committed to their preferred outcome to be well prepared for the labyrinth of choices that would soon confront them.

Similarly, I don’t believe Nick Clegg had really gamed out the dilemma his push for electoral reform would place all leaders in, as they became exposed to the unpredictable and shifting preferences of their own and each others’ backbenchers; and – through a referendum – to those of the public.

I wonder too whether Labour ‘strategists’ (most of whom are actually dyed-in-the-wool tacticians) saw credible routes to power if Gordon Brown resigned. Or was this merely a Hail Mary pass disguised as a game-changing moment?

(My first thoughts when Brown used his decision to stand aside as a negotiating ploy were: (i) Which of the leadership candidates were involved in the decision? And (ii) Will this later be seen in the same light as McCain’s surprise announcement that an unknown Alaskan governor was joining him on the Presidential ticket?)

In conditions of uncertainty, parties need what I think of as resilient strategies – ones that are not easily shifted from long-term goals, but blend this with a sensitivity to unpredictable outcomes, and which look beyond preferred outcomes to encompass a ‘plan b’ (c, d, e…) for failure.

So here’s a question for parties. Which of them has a ‘red team’ that has been isolated from the negotiations and has been asked to think simply about how the party should react to a ‘no deal’?

During the negotiations, the Tories have made major policy shifts, which they are going to find hard to reconcile with their core platform. Labour has initiated what is likely to be a long and acrimonious leadership campaign, which is going to turn it inwards at a time of national crisis. And the Liberal Democrats have sacrificed their reputation as standing for something other than the ‘same old politics’.

Each of them – in different ways – now stands on unstable ground. Unless their strategies are resilient to changed circumstances, they could find their support eroding very fast indeed.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 6, 2010 | Global system, UK

It’s a fitting end to the British general election.

We have had thirty years of entrenched majorities – as a dominant party defined the terms of the debate, and the media made sure the opposition never caught a break. In 1997, the swing from Conservative to Labour dominance was sudden and decisive.

Now we have an utterly unpredictable polling day. Tiny shifts in the share of vote between parties and, especially, its geographical distribution could have a disproportionate impact on the political landscape that emerges on Friday.

If it’s close, it will all come down to spur-of-the-moment decisions by three very tired men. Constitutionally, Brown remains Prime Minister until someone else can command ‘the confidence of the House.’

As incumbent, he also should get first dibs on forming a new government, though it is widely expected that Cameron will declare victory early, and use the media to establish his right to govern.

As Alex has warned, there’s also a possibility that the bond markets will push the pace, as they open at 1 a.m. tomorrow morning to react to election news. Yields on UK 10-year bonds have spiked this morning, but are still lower than they have been for much of the year.

If Cameron gets the most votes and the most seats, he’ll surely go on to form a government. If not, a period of Florida-style uncertainty seems more than possible. What, one wonders, will be the UK’s equivalent of the hanging chad?

Either way, we can expect some exceptionally close Commons votes, perhaps a referendum on electoral reform, and – surely – a Parliament that won’t last for a full term. That means more elections for parties that have bankrupted themselves during this one.

This unaccustomed volatility in the electoral system seems curiously appropriate. As the past few years have shown, we now live in an era where the UK is far from being in control of its own destiny.

Look forward and we can expect the following forces to frame the government’s strategic choices.

First, global risks will continue to drive domestic policy. Voters will not actively call for a more effective foreign policy, but they will notice and bemoan its absence.

Global forces will continue to have considerable impact on their lives, with the main sources of strategic surprise coming from beyond the UK’s borders.

Over the next ten years, moreover, most risks will be on the downside. We have lived, as I have argued, through a volatile decade. There is every reason to expect risks to continue to proliferate.

Each new crisis will create political aftershocks with demands for governments to clear up the mess, matched by inquiries into why they failed to prevent the problem in the first place.

Finally, the government will find that, in most cases, it does not have the levers to manage risks as effectively as it would like to.

Whatever the next Prime Minister wants to do, he is going to find that global volatility, a lack of money, and government mechanisms that are equipped for the problems of another age, constrain his scope for action.

On top of that, he’ll only be able to solve problems if he can rustle up a coalition of other countries, all of whom will be beset by the same problems.

If – and it’s a big if – there is to be a new dominant paradigm in British politics, replacing those established by Thatcher and New Labour, then it will be because a leader emerges who has the skill to govern well in an age of global uncertainty.

I can’t imagine a more exciting time to pitch up in Downing Street, but it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 3, 2010 | Middle East and North Africa

From Cumberland Advisors, a sobering analysis of the possible fallout from the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Three bleak scenarios are set out. According to the report, there is no ‘good’ outcome at this stage:

The Bad.

Containment chambers are put in place and they catch the outflow from the three ruptures that are currently pouring 200,000 gallons of oil into the Gulf every day. If this works, it will take until June to complete. The chambers are 30-foot-high steel configurations that must be placed on the ocean floor at a depth of one mile. This has never been done before. If early containment is successful, the damages from this accident will be in the tens of billions. The cleanup will take years. The economic impact will be in the five states that have frontal coastline on the Gulf of Mexico: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

The Worse.

The containment attempts fail and oil spews for months, until a new well can successfully be drilled to a depth of 13000 feet below the 5000-foot-deep ocean floor, and then concrete and mud are injected into the existing ruptured well until it is successfully closed and sealed. Work on this approach is already commencing. Timeframe for success is at least three months. Note the new well will have to come within about 20 feet of the existing point where the original well enters the reservoir at a distance of 3.5 miles from the surface drilling rig. Damages by this time may be measured in the hundreds of billions. Cleanup will take many, many years. Tourism, fishing, all related industries may be fundamentally changed for as much as a generation. Spread to Mexico and other Gulf geography is possible.

The Ugliest.

This spew stoppage takes longer to reach a full closure; the subsequent cleanup may take a decade. The Gulf becomes a damaged sea for a generation. The oil slick leaks beyond the western Florida coast, enters the Gulfstream and reaches the eastern coast of the United States and beyond. Use your imagination for the rest of the damage. Monetary cost is now measured in the many hundreds of billions of dollars.

by David Steven | Apr 29, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

If the BBC leaders’ debate tonight devotes more time to bigotgate than to housing, I am going to dedicate the rest of my days to working for the Corporation’s demise.

Britain’s unsustainable housing market is at the root of many of the country’s problems and could wreak appalling damage on voters during the next parliament. It must feature in the debate.

Someone should start by reminding Gordon Brown of a promise he made in his first budget speech in 1997:

Stability will be central to our policy to help homeowners. And we must be prepared to take the action necessary to secure it. I will not allow house prices to get out of control and put at risk the sustainability of the recovery.

As I argued recently:

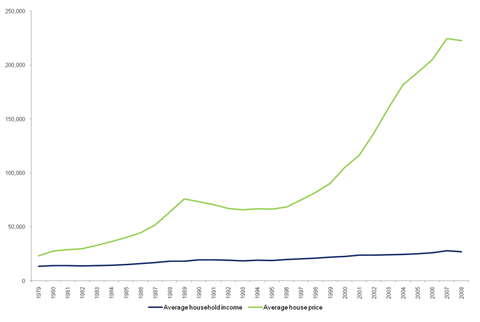

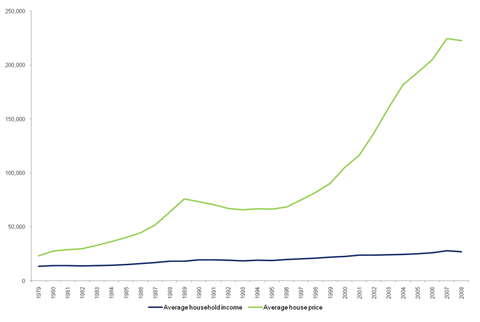

When Brown spoke, the average house cost £75k – about £10k above the early 1990s nadir. A long long boom was just beginning. Prices would peak in February 2008 at an average of… £232k!!!

In other words, Brown promised not to let house prices spiral out of control and then allowed them to treble, during a period when household disposable income increased by only 30% or so.

2007 saw what is often called a housing price crash, but as this graph shows, it was really only a blip.

As the government pumped money into the economy and pushed interest rates to unprecedented low levels, the bubble started to inflate again. House prices are now back to the levels of June 2007.

Second guessing the housing market is a mug’s game, surely this is unsustainable. British houses are overvalued by nearly a third, according to one measure. Worse is the amount of mortgage debt outstanding – $1.238 trillion. By comparison, government debt is ‘only’ £950 billion.

Low interest rates and buoyant employment (relative to the economy’s woeful performance) have kept householder’s head above water – but the highly-indebted remain highly vulnerable to any increase in interest rates or to further job losses.

My best case for the housing market is a long period of stagnation (we desperately need lower prices). Worst case would be a sudden, vicious and self-fulfilling collapse. I believe this is currently the most serious economic risk facing the British people (one which is, of course, interrelated to Europe’s sovereign debt problems).

So what do the major parties have to say about this in their manifestos?

- Labour wants to expand home ownership and exempt all houses under £250k from stamp duty (likely to push house prices up). It says it will build 110k houses over two years (likely to push prices down).

- The Conservatives promise to exempt first time buyers from stamp duty if their house costs less than £250k. It wants to put communities in charge of planning, which is highly likely to reduce the number of houses built.

- The Lib Dems plan to use loans and grants to bring 250k empty houses back into use.

Pretty weak beer, all told. No party questions the shibboleth that Britain needs more homeowners. None is prepared to explain how they will manage risks that have been increased by the response to the financial crisis.

Far less do they have policies to fulfil Brown’s promise from 1997 – to end boom and bust in the housing market radical proposals (see my Long Finance paper) to prevent the mortgage market from screwing borrowers every twenty years or so.

So here’s my question for tonight’s debate:

In 1997, Gordon Brown promised he’d never let house prices get out of control again, but then presided over a housing bubble that has left British householders owing £1.2 trillion on their mortgages. In government, what will you do to stop the housing dream from becoming a housing nightmare?

by David Steven | Apr 27, 2010 | UK

It is often in the aftermath of a crisis that the government definitively loses control of the agenda – it moves on, while the media cements its narrative on who was to blame, and why.

So it is with the ash cloud. We are told that the Met Office plane that should have been up in the air monitoring the ash cloud was undergoing a refit. As a result, many journalists are now convinced the whole crisis was a con. “Remember that ash cloud?” asks the Daily Mail. “It doesn’t exist, says new evidence.”

Jim McKenna, the Civil Aviation Authority’s head of airworthiness, strategy and policy (great combo), appears to admit the decision to close British airspace was a cock up:

It’s obvious that at the start of this crisis, there was a lack of definitive data. It’s also true that for some of the time, the density of ash above the UK was close to undetectable.

Head to the CAA website, however, and you won’t find anything on these claims. The most recent item on the ash cloud is a highly-defensive op-ed from its chairman [sic], Dame Deirdre Hutton, written three days ago. There’s nothing at all from Jim McKenna – either to explain what went wrong, or to place his quote in a broader context.

NATS stopped updates on the volcano on Friday, while the Met Office’s website is a car crash, and its latest update typifies the jargon-heavy style that the UK’s weathermen and women have made their own. Here’s a defence of the Met’s predictions in the nearest the Met comes to using plain English (more detail here):

We use multiple dispersion models endorsed by the international meteorological community. The output from the Met Office volcanic ash dispersion model has been compared with our neighbouring VAACs in Canada and France since the beginning of this incident and the results are consistent.

The results from our model have been verified by observations of volcanic ash from a variety of sources, including from instruments carried by Met Office, FAAM and NERC research aircraft, balloon and land based LIDARS.

So did the cloud exist? Was Jim McKenna the source of newspaper claims that “the maximum density of the cloud was only five per cent of the safe flying limit”? Who knows? And there seems to be little chance of the UK’s public sector telling you.

Update: Just because it’s wonderful, have a butchers at this superb video of Europe’s airports coming back to life.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/11205494[/vimeo]