by Seth Kaplan | Jun 20, 2012 | Conflict and security, Economics and development

The term “fragile states” is much abused.

Policymakers, development researchers, politicians, and the media seem to think that every country experiencing a period of instability or bothered by certain governance problems is “fragile.” As a result, they group a wide range of countries experiencing vastly different types of problems together—creating a mass of confusion in the process.

Such thinking means that the term as currently used has very little value as an analytical tool. Instead it has become a catchall phrase to explain any situation that seems “fragile” even if the fragility is likely to be ephemeral. It also means that states that are structurally fragile but that have none of the most obvious symptoms of fragility (such as Syria before 2011) do not get considered as one. (more…)

by David Steven | Dec 9, 2011 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, UK

What a day. Five observations:

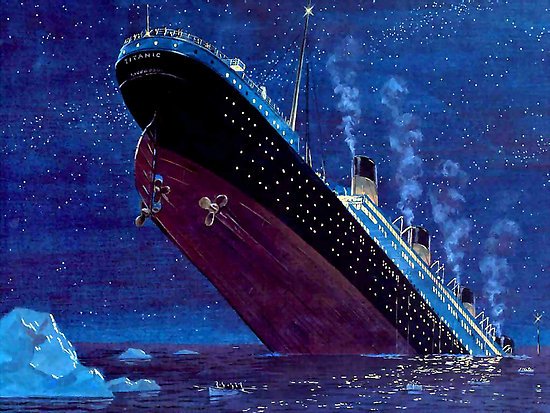

- My initial reaction this morning: On a sinking Titanic, the UK is lobbying to avoid further damage to the iceberg. If David Cameron was motivated mostly by his wish to suck up to the City (and to his backbenchers), then he deserves all that fate can throw at him. He has transformed eventual British exit from the EU from Eurosceptic fantasy to the new conventional wisdom in just 12 hours. Quite a feat.

- But maybe… his government has decided that the euro is now doomed and has made a rational decision to swim as far from the vortex as possible. Many believe that a disorderly break up of the single currency has become more likely than not. That would probably cost the UK 10% of GDP and make British default a near certainty. But if that’s what’s going to happen, then we better knuckle down to being as resilient to the shock as possible.

- The British veto makes euro failure more, not less, likely. In theory, agreement between a core group is easier than having all 27 countries in the room, but the legal complications of conjuring a new set of institutions from thin air are daunting. Also, expect the core to shrink as the summit’s aspirations are chewed up by domestic politics. Each defection will provide a potential trigger for wider breakdown – probably when a group of the strong decide all hope is lost, and make a collective rush to the lifeboats. By being the first to desert the ship, Cameron has made it much easier for other European leaders to follow.

- Contingency planning must now go much deeper. Behind the scenes, governments are playing out failure scenarios, and most big businesses have some kind of post-euro plan in place. Much of the thinking is still pretty rudimentary, however. The eurozone countries can’t risk letting markets see them flinch and have to put a brave face on their prospects, but the UK no longer needs to have such scruples. What exactly would we do if the euro goes down? What would be thrown overboard? What, and who, would be saved? How can the government organise effective collective action as the catastrophe hits?

- Nick Clegg is dead, politically. That was already true, but I can’t imagine even Miriam González Durántez now plans to support her husband at the next election. Paradoxically, accepting his terminal status could give Clegg new freedom of action. Instead of continuing to play the role of coalition gimp, he should offer leadership to those keen to explore what comes after the storm. Politicians with proper jobs – Cameron, Osborne, even Cable – are going to be overwhelmed by events throughout this parliament, even in the best case where Europe struggles back onto its feet. Clegg, though, has an opportunity to focus energy on the longer term. He’ll still lead the Lib Dems to electoral Armageddon, but catalysing a vision for renewal might make posterity a little kinder to the poor man.

by Jules Evans | Feb 7, 2011 | Climate and resource scarcity, Conflict and security, Influence and networks

Nice to see Keith Olbermann reads Global Dashboard. In January, shortly before MSNBC fired him, Olbermann did a story on the US Army’s ambitious resilience training programme, which I reported on back in October 2009. Olbermann reports that some atheist soldiers are objecting to the ‘spiritual fitness’ aspect of the programme, which rates to what extent soldiers feel ‘connected to humanity’ and guided by ‘a sense of meaning’ etc. Olbermann then quotes my interview with the programme’s director, Rhonda Cornum, where she says ‘every time you say the S-P-I-R word you’re going to get sued’. If you look really carefully under the photo of Cornum, you can see ‘Source: globaldashboard.org’.

To be fair to Cornum and the programme’s designer, Martin Seligman of Penn University, I would not say the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness programme is ‘religious’, or ‘Christian’. Martin Seligman is Jewish, for one thing. But he does believe, and has evidence to show, that part of being a resilient person is having a sense of meaning in one’s life. That’s not the same as religion. I would have thought atheists could see that…

But I thought that the politics of wellbeing would get into these problems. As soon as a liberal government backs one version of the Good Life, it’s going to be accused of violating the freedom of conscience and religious belief. That’s the challenge facing pluralist, multicultural societies – how to create a sense of unity, cohesion and common values in our society (including in our armies) without being accused of forcing your beliefs onto other people. Still, this seems a pretty unbalanced news story to me.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GNfBPXi5rUA[/youtube]

by David Steven | Jan 19, 2011 | Climate and resource scarcity, South Asia

Recently, I wrote about the devastating – and largely unreported – impact that resource scarcity is having on Pakistan’s fragile economy and society. Barely a day goes by without a new data point that illustrates the size of the problem.

Today, for example, the papers report that the two main political parties (the ruling PPP, and its arch opponents, PML-N) have come together to try and fix an economic crisis that they admit has its main roots back in the 2008 resource price spike:

Sources said the government had told almost all parties that most of the economic pressure had built up because of carryover of huge fiscal deficit from the previous government which did not pass on energy prices to consumers even when international oil prices increased from $90 to $147 a barrel and the current government was facing a similar situation. Most public sector corporations have since been bleeding mainly because of this single factor.

Power companies are getting so desperate for fuel oil (which they are using to replace gas, whose shortage has led to an electricity crisis), that they’re signing sovereign-backed contracts for imports on deferred payments, going against the express wishes of the state-run Pakistan Oil Company, and, seemingly, without explicit permission from the government.

In Punjab, meanwhile, grain markets are grinding to a halt, as the government attempts to tax agricultural production in order to plug its yawning fiscal hole and – I suspect – to make it politically easier to raises taxes on urban consumption. Traders are on strike, accusing the government of destroying the ‘backbone’ of the economy.

The impact on ordinary people is marked. The gas shortage is pushing urban residents back towards a reliance on biofuel. “I am purchasing stove to use firewood in the 21st century thanks to the government,” complains one resident of Rawalpindi.

Fortunately, food shortages are yet to hit one of the citizens of nearby Islamabad: President Zardari. He has his own camel in the Presidential Palace, because he thinks the milk is healthier.

The President House also has a herd of black goats. One goat is slaughtered everyday when Mr Zardari is there.

Earlier, his trusted personal servant, Bai Khan, used to buy a goat from Saidpur village every day, but now a herd has been kept in the presidency to avoid frequent visits to the animal market. The animal is touched by Mr Zardari before it is sent to his private house in F-8/2 for slaughtering.

Good to see one man, at least, taking resilience seriously.

by Alex Evans | Dec 7, 2010 | Cooperation and coherence

A French court yesterday found Continental Airlines guilty of involuntary homicide for its part in the Concorde crash outside Paris in 2000. This is regrettable, since criminalising accidents is not an intelligent approach to managing risk.

The reason Continental found itself in the dock on this case was that the last plane to take off before Concorde, a Continental DC10, shed a small piece of titanium that then punctured a tyre on the Concorde, which then led to shards of rubber flying into the fuel tanks. Not only was Continental prosecuted, but so was the individual mechanic – one John Taylor, who’s been given a fine and a suspended sentence.

Compare this to the approach taken to error reporting in high-reliability organisations. Here are Karl Weick and Kathleen Sutcliffe in their classic book on the subject, Managing the Unexpected:

The best high reliability organisations increase their knowledge base by encouraging and rewarding error reporting, even going so far as to reward those who have committed them … researchers Martin Laundau and Donald Chisholm provide [the example of] a seaman on the nuclear carrier Carl Vinson who reported the loss of a tool on the deck. All aircraft aloft were redirected to land bases until the tool was found, and the seaman was commended for his action – recognizing a potential danger – the next day at a formal ceremony.

That’s what you want to happen – a transparent organisational culture that displays what Weick and Sutcliffe call “a preoccupation with failure”.

It’s also the precise opposite of what the French court has effectively just ensured – which is that mechanics will keep schtum about their mistakes in case they get prosecuted. Not clever.