by David Steven | Apr 18, 2010 | UK

Yesterday, I warned that governments were losing control of the Eyjafjallajökull crisis:

In the UK, it doesn’t help that there’s an election on. But Lord Adonis, the Secretary of State for Transport, is not running for office. It would be good to see greater signs that he – or someone else – is being much more decisive about taking charge.

Apparently, there are more than a million British citizens still stranded abroad and the MET Office has said there will be no flights on Monday 18 April (no confirmation from NATS on that as yet). Both the media and airlines are clearly getting restless. A new narrative is crystallizing: that the threat from the ash cloud has been substantially exaggerated.

Albeit belatedly, British ministers have finally shown they are now more fully engaged with events, with five lining up in Downing Street for a press conference. COBRA will meet tomorrow morning.

In my opinion, however, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office should be much more specific about what its consular staff are doing. I’m talking about concrete and detailed briefing for the media.

How is it using its consular surge capacity (the Rapid Deployment Team)? How many extra staff have been deployed? In which airports does it have staff dealing directly with passengers and airlines? How, practically, are these staff managing to assist people?

The generalities on the FCO website are not nearly enough… [Relatedly: KLM masters social media. Air France fails.]

Update [19/04 9.30 am]: A few other thoughts. The UK government social media response has – so far – been distinctively unimpressive, despite the fact that many government departments, the FCO included, have very good social media team. (Good this morning, though, to see the gov Twitter feeds finally starting to use the Twitter #ashtag and #ashcloud tags)

In contrast, Eurocontrol – which oversees European airspace – has emerged as a model of best practice. Whoever it behind its Twitter feed is doing a stellar job – detailed factual updates, numerous responses to people’s questions, and all in an identifiably human voice.

Also, the pressure is clearly building on governments to downgrade the threat, based on test flights. But, say, a plane had a 1/1000 risk of getting into trouble (e.g. hitting a slightly thicker patch of ash during its flight), then you could run a dozen or so tests and have a very slim chance of hitting trouble. So you open Heathrow, which has 1300 flights every day…

Once again, the complex risk calculations at the heart of this crisis are making Anthony Giddens’s 1999 Reith lecture look very prescient:

There is a new moral climate of politics, marked by a push-and-pull between accusations of scaremongering on the one hand, and of cover-ups on the other. If anyone – government official, scientific expert or researcher – takes a given risk seriously, he or she must proclaim it. It must be widely publicised because people must be persuaded that the risk is real – a fuss must be made about it. Yet if a fuss is indeed created and the risk turns out to be minimal, those involved will be accused of scaremongering.

Suppose, on the other hand, that the authorities initially decide that the risk is not very great, as the British government did in the case of contaminated beef. In this instance, the government first of all said: we’ve got the backing of scientists here; there isn’t a significant risk, we can continue eating beef without any worries. In such situations, if events turn out otherwise – as in fact they did – the authorities will be accused of a cover-up – as indeed they were.

Things are even more complex than these examples suggest. Paradoxically, scaremongering may be necessary to reduce risks we face – yet if it is successful, it appears as just that, scaremongering. The case of AIDS is an example. Governments and experts made great public play with the risks associated with unsafe sex, to get people to change their sexual behaviour. Partly as a consequence, in the developed countries, AIDS did not spread as much as was originally predicted. Then the response was: why were you scaring everyone like that? Yet as we know from its continuing global spread – they were – and are – entirely right to do so.

This sort of paradox becomes routine in contemporary society, but there is no easily available way of dealing with it. For as I mentioned earlier, in most situations of manufactured risk, even whether there are risks at all is likely to be disputed. We cannot know beforehand when we are actually scaremongering and when we are not.

When dealing with risk, governments are almost always going to emerge at least somewhat discredited. The question is how badly

Update II [19/04 16.30]: The FCO website is still maddeningly unspecific. For example:

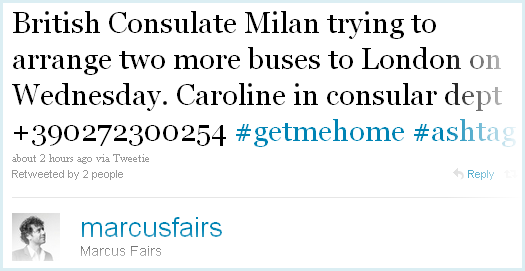

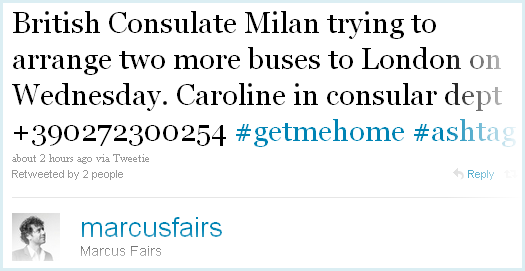

Meanwhile, here’s Marcus Fairs with some information that’s (i) much more specific and helpful; (ii) directly covers what named FCO consular staff are up to.

Also, it is increasingly clear that NATS – the UK’s air traffic control organisation – is floundering. No Twitter feed. A website that is still in emergency mode. And, worst of all, official updates on their site, but leaks to other news organisations with different information. Not good.

Update III [20/04 14.30]: Finally:

by David Steven | Mar 1, 2010 | Europe and Central Asia, Influence and networks, UK

It’s taken as a given here in the UK that Brits wield little influence in Europe. But apparently – not. According to the Guardian, an FCO-led coup is under way:

Germany is planning to stop what it sees as a British campaign to dominate European foreign policy-making under Lady Catherine Ashton, the Guardian can disclose.

Amid growing criticism across the EU of the performance of Baroness Ashton of Upholland, the EU’s new high representative for foreign and security policy, Berlin and Paris are alarmed at the prominence of British officials in the new EU diplomatic service being formed under Ashton.

A confidential German foreign ministry document analysing the creation of the EU’s new diplomatic service, seen by the Guardian, has concluded that Britain has grabbed an “excessive” and “over-proportionate” role…

The French contend that the inexperienced Ashton is being schooled in policy-making by the Foreign Office. Diplomats and officials in Brussels also see Britain’s hand in one of Ashton’s first appointments, made last week. She named Vygaudas Ušackas, a former Lithuanian foreign minister and ambassador in London, as the EU’s special envoy to Afghanistan. He was widely seen as the UK’s favoured contender after Britain withdrew its own candidate because it secured the post of Nato envoy in Kabul.

The Germans are also increasingly unhappy at what they see as the erosion of their influence and being cut out of decision-taking.

by David Steven | Feb 22, 2010 | UK

The eruption of bullygate reminds me of this recent exchange between Labour MP, Sandra Osborne, and Peter Ricketts, the Foreign Office’s Permanent Secretary:

Osborne: Could I ask you about staff morale as far as bullying, harassment and discrimination is concerned? In the staff survey of 2008-I know that Mr. Bevan referred to the 2009 survey, which has not yet been published-17% of all FCO staff reported experiencing this, and it was only 11% on average across Whitehall. Also, 20% of locally based staff reported this, as opposed to 14% of UK-based staff. How do you explain this relatively high level of reporting of harassment and bullying?

Ricketts: First, can I say that I find it absolutely unacceptable? It’s something that we are worried about and working on. We are very, very keen to see that we get to the bottom of it and root out whatever the problems are. Mr. Bevan can give you details of where we are in the 2009 staff survey. To our real disappointment, that number has not come down very significantly. It has come down from 17 to 16%, which is not good enough, so we have to continue to tackle this problem seriously.

Part of it is understanding exactly what is going on here. We put together bullying, harassment and intimidation, and I need to understand more about what are the actual problems that staff are reporting there, because any suggestion of bullying or harassment is completely unacceptable. Indeed, we are prepared to take staff out of positions abroad and bring them home if we see evidence of behaviour that is bullying or harassment, and we have done that, so we’re trying to send the strongest signal we can, which is taking people out of their postings and bringing them back to London if we see evidence of that.

Osborne went on to point out that “reported levels of discrimination, bullying or harassment tended to be higher among the staff at lower grades, disabled staff and minority ethnic groups, black staff in particular.” James Bevan, the FCO’s DG for Change and Delivery, replied:

You are right. We were so concerned by the 17% figure from the last survey that we commissioned a more detailed analysis of what the data were telling us, and they told us that, by and large, the allegations tend to relate to junior officers who feel that they are being bullied by senior officers and to local staff who sometimes feel that they are being bullied by UK staff, and that there is a higher prevalence of reported experience of this behaviour from black minority ethnic and other minority groups.

One thing that I have done is to meet with representatives of the black staff to talk through why they think this is happening. I have to say that there were some very convincing stories which resulted in my writing to all our heads of mission abroad to say that we are particularly concerned at the high levels of reported behaviour affecting black and minority ethnic staff and that we wanted to crack down on it absolutely to make sure that it reduces next year. The task for us now is to analyse the latest data in the new survey and see if that has happened. If it has not, we will have to keep going.

It’s a worrying finding.

Update: It turns out these are not new findings. From 2006:

One in ten government workers in Whitehall say that they are being bullied, a staff survey has revealed. The research says that the figure rises to one in three in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, with black and Chinese employees suffering the worst harassment.

by Michael Harvey | Nov 20, 2009 | Conflict and security, Europe and Central Asia, Influence and networks, North America

– With the new EU President and High Representative finally decided, the FT wonders whether current Commission President, José Manuel Barroso, is the true victor from all the horse-trading. The Times has news that, consistent with the Lisbon reforms, the EU is attempting to strengthen its presence at the UN. Sunder Katwala, meanwhile, suggests that European member states still lack a fundamental sense of what they want to achieve as one in the global arena.

– As President Obama continues to review Afghan strategy, the WSJ assesses the impact on US-UK relations. Con Coughlin, meanwhile, paints a more pessimistic picture of the “exclusivity of [Obama’s] style of decision-making”.

– Elsewhere, Fyodor Lukyanov heralds Mikhail Gorbachev’s idealism, suggesting he was “the last Wilsonian of the 20th century”. Richard Haass, meanwhile, explains how lessons drawn from the Cold War could help address contemporary global challenges.

– Finally, World Politics Review has a series of articles on modernising the US State Department and creating a more integrated national security architecture. The Guardian, meanwhile, surveys the UK Foreign Office’s growing “brave new world of blogger ambassadors”.

by Alex Evans | Jul 7, 2009 | Conflict and security, Global Dashboard

Time was when any suggestion that conflict prevention might be central to development would be met by blank (if not outright hostile) stares at DFID’s headquarters – but DFID’s latest White Paper, published yesterday, certainly puts that attitude to rest for good.

Fully half of new UK bilateral aid will focus on conflict-affected and fragile states; there will be an intensive focus on job creation in five at-risk countries (Yemen, Nepal, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Afghanistan); security is for the first time defined as an essential service, like health or education; there’s lots of additional focus on SSAJ (safety, security and access to justice); and there’s plenty more besides.

Now, sharp-eyed conflict watchers among you will already be wondering: does all this mean that the cuts to UK conflict prevention spending announced by David Miliband in March this year are effectively reversed?

(The problem, readers will recall, was that while peacekeeping missions were mushrooming – MONUC, UNMIS and the AU mission in Somalia in particular – the pound was collapsing against the dollar and the euro, the currencies in which peacekeeping bills are denominated. This was driving a coach and horses through the planned cross-governmental conflict prevention budget of £556 billion – comprised of £109m for the Conflict Prevention Pool, £73m for the Stabilisation Aid Fund and £374m for peacekeeping missions. The peacekeeping bit would now have to rise £456 million. So even after DFID and MOD had lobbed in an extra £71 million, it was clear that tough cuts would have to be made – a point made with anguish in a letter to the FT in March from foreign policy luminaries including Lords Ashdown, Hannay, Howe, Jay, Kerr, Robertson and Wallace. Now read on..)

Well, now that DFID’s Secretary of State Douglas Alexander is promising that the UK will spend £1 billion a year in post-conflict countries, it’s clear that much of the money that was cut in March will effectively be available again – though you’ll have a fight on your hands to get DFID to admit this to be the case, since it’s shy of creating any impression that it’s there to bail out other departments when the full, epic sweep of spending cuts becomes clear after the election.

But we’re nonetheless in a new situation, rather than back to the status quo ante, in at least three important ways. (more…)