by Mark Weston | May 7, 2013 | Africa, Economics and development

Sunday’s El País carried a surprising article detailing the increase in immigration from Africa to Spain in the past two years.

Although Spain is in the midst of a debilitating economic crisis, with an unemployment rate of over 27%, the number of would-be migrants crossing the Strait of Gibraltar from Morocco in the first quarter of 2013 has quadrupled compared with the corresponding period in 2012. Alarmingly, the proportion using inflatable rubber dinghies – the kind your kids play on at the beach – has risen from 15% to 90% in the past year. These dinghies are designed to be used by two people, but in the Strait they are often intercepted with up to ten on board (Spain’s coastguard has yet to hear of one that has completed the fourteen kilometre journey – the lucky ones are rescued before they sink). In Morocco, the market in these vessels is thriving – a 2-3 metre boat that can be had for €300 in the Spanish beach resorts will set you back over €600 in Tangiers.

This continued flow of migrants from Africa to Europe gives the lie to the “Africa Rising” story peddled by some Western media outlets of late. Although GDP is growing in many parts of the continent, most Africans see nothing of this. The millions who have migrated from villages to cities in search of a better life too often end up with nothing to do, and in their desperation are forced to look further afield, to Europe, for a way out of poverty (as the chief prosecutor in the Spanish port town of Algeciras noted, ‘many people would love to have our crisis’).

While researching my new book, The Ringtone and the Drum: Travels in the World’s Poorest Countries, which as well as analysing the great social upheavals the developing world is going through as it modernises is an attempt to give voice to the people experiencing these changes on the ground, I observed this frustration at first hand. The population of Bissau, the capital of the tiny West African nation of Guinea-Bissau which was the first stop on my trip, has quadrupled in the past thirty years. Whole villages in the interior have emptied out as the land has become too crowded to farm and the lure of modernity entices people to the cities. My wife Ebru and I spent a few weeks in one of Bissau’s poorest districts, where, as the excerpt below shows, urbanisation’s losers face a constant dilemma over whether they too should undertake the perilous journey to the West:

Since there is no power and the heat quickly rots anything perishable, Bissau’s residents must lay in a new supply of food each day. Every morning, therefore, we walk down the paved but potholed road that leads from our bairro to Bissau’s main market at Bandim. The market is a labyrinth, its narrow dark lanes winding between rickety wooden stalls whose tin roofs jut out threateningly at throat height. A press of brightly-dressed shoppers haggles noisily over tomatoes, onions, smoked fish and meat. The vendors know their customers – you can buy individual eggs, teabags, cigarettes, sugar lumps and chilli peppers; bread sellers will cut a baguette in half if that is all you can afford; potatoes are divided into groups of three, tomatoes into pyramids of four; matches are sold in bundles of ten, along with a piece of the striking surface torn from the box. In the days leading up to Christmas and New Year, which all Guineans celebrate regardless of their religious persuasion, the market is crowded and chaotic, but after the turn of the year, when all the money has been spent, it is empty and silent.

Only the alcohol sellers do a year-round trade. On a half-mile stretch of the paved road there are thirteen bars or liquor stores. They sell cheap Portuguese red wine, bottled lager, palm wine and cana, a strong rum made with cashew apples. Bissau has a drink problem. Its inhabitants’ love of alcohol is well-known throughout West Africa. Back in Senegal, a fellow passenger on one of our bush taxi rides had warned us that Guineans ‘like to drink and party but they don’t like to work.’ Later in our trip, on hearing we had spent time here, Sierra Leoneans would talk in awed tones of Guineans’ capacity for alcohol consumption. The liquor stores near our bairro are busy at all hours of the day and night. Christians and animists quaff openly, Muslims more discreetly. (more…)

by Alex Evans | Oct 19, 2012 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Influence and networks

The FT’s Gillian Tett reports today on a conference presentation given by historical sociologist Dennis Smith, who’s been working on the question of how humiliation operates at the cultural / collective psychological level – and what this means for the Eurozone.

The whole article‘s worth reading, but here are a couple of highlights. First, on how humiliation works:

Psychologists believe the process of “humiliation” has specific attributes, when it arises in people. Unlike shame, humiliation is not a phenomenon which is internally driven, that is, something that a person feels when they transgress a moral norm. Instead, the hallmark of humiliation is that it is done by somebody to someone else.

Typically, it occurs in three steps: first there is a loss of autonomy, or control; then there is a demotion of status; and last, a partial or complete exclusion from the group. This three-step process usually triggers short-term coping mechanisms, such as flight, rebellion or disassociation. There are longer-term responses also, most notably “acceptance” – via “escape” or “conciliation”, to use the jargon – or “challenge” – via “revenge” and “resistance”. Or, more usually, individuals react with a blend of those responses.

So what does that mean for European politics? Well, Tett continues, the Eurozone’s periphery countries have indeed experienced “a loss of control, a demotion in relative status and exclusion from decision making processes (if not the actual euro, or not yet)” – and it’s interesting to observe how different European countries have used different coping strategies:

National stereotypes are, of course controversial and dangerous. But Prof Smith believes, for example, that Ireland already has extensive cultural coping mechanisms to deal with humiliation, having lived with British dominance in decades past. This underdog habit was briefly interrupted by the credit boom, but too briefly to let the Irish forget those habits. Thus they have responded to the latest humiliation with escape (ie emigration), pragmatic conciliation (reform) and defiant compliance (laced with humour).“This tactic parades the supposedly demeaning identity as a kind of banner, with amusement or contempt, showing that carrying this label is quite bearable,” says Prof Smith. For example, he says, Irish fans about to fly off to the European football championship in June 2012 displayed an Irish flag with the words: “Angela Merkel Thinks We’re At Work”.

However, Greece has historically been marked by a high level of national pride. “During 25 years of prosperity, many Greek citizens had been rescued by the expansion of the public sector?.?.?.?they had buried the painful past in forgetfulness and become used to the more comfortable present (now the recent past),” Prof Smith argues. Thus, the current humiliation, and squeeze on the public sector, has been a profound shock. Instead of pragmatic conciliation, “a desire for revenge is a much more prominent response than in Ireland”, he says, noting that “politicians are physically attacked in the streets. Major public buildings are set on fire. German politicians are caricatured as Nazis in the press?.?.?.?the radical right and the radical left are both resurgent.”

Prof Smith’s research has not attempted to place Spain on the coach. But I suspect the nation is nearer to Greece in its instincts than Ireland; humiliation is not something Spain has had much experience of “coping” with in the past. Whether the Spanish agree with this assessment or not, the key issue is this: if Angela Merkel or the other strong eurozone leaders want to forge a workable solution to the crisis, they need to start thinking harder about that “H” word. Otherwise, the national psychologies could yet turn more pathogical.

by Mark Weston | Jun 26, 2012 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Influence and networks

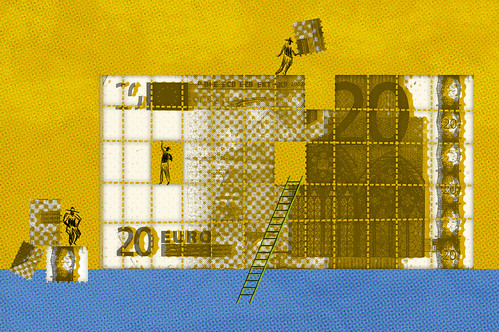

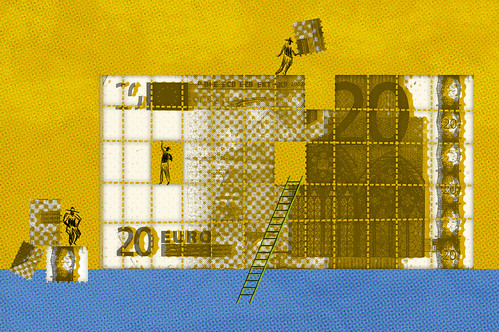

Image: Colbrain crowdfunding

Following the collapse of the bank he was running until earlier this year, Rodrigo Rato probably thought he would be able to slip into a quiet, if tarnished retirement.

A former managing director of the IMF and minister of the economy during Spain’s boom years, Rato stepped down as executive chairman of Bankia in May after steering the group onto the jagged rocks of a €4.5b government bailout. Rato had bragged about the bank’s huge portfolio of loans and deposits, and it was floated with great fanfare on the stock exchange last summer. Within a year, however, buckling under the weight of a mountain of bad loans, the bank had had to be part-nationalised (for a description of how it happened, see this FT article). As well as institutional investors, hundreds of thousands of unwary Bankia customers and thousands of members of staff persuaded by their trade union that the stock was a safe investment found themselves out of pocket.

A few weeks after Rato’s resignation, his successor revealed that the net profit of €309m in 2011 that the bank had reported was in reality a €3b loss. The stricken entity would need an additional €19b bailout, and become the major trigger for the European Union rescue package announced by an embarrassed Spanish government earlier this month.

This latter revelation sparked the interest of Spain’s “indignados”, the loose association of young protesters who spent much of the middle part of 2011 camped out in the main squares of Spain’s biggest cities. The movement has been fairly quiet of late, but the Bankia debacle has roused it from its slumber. Deciding that Spain’s bankers had been getting away for too long with misleading the government, shareholders, customers and, well, everyone else, they took action.

The target was Rodrigo Rato, the idea to sue him and his colleagues for falsifying the firm’s accounts in the lead-up to the IPO. Having obtained support and crucial information on the board’s activities from a group of ten disgruntled shareholders, the indignados’ umbrella organisation 15-M needed to find €15,000 to meet the costs of filing the suit (the breakdown of those costs is detailed on the group’s website). Many of its members are unemployed, many others are students or low-paid workers. None had the means to take legal action single-handedly. What to do?

Ingeniously, they turned to crowdfunding to raise the money. Like its more famous cousin Kickstarter, the website goteo.org allows those in need to solicit funds from anyone who feels like contributing. In late May, therefore, as El País reports, 15-M began a Twitter campaign to drum up interest, under the hashtag #15MpaRato. At 9am on 5 June, the goteo.org page was launched. Within an hour it had received 11,000 visits. By 2pm it was in danger of crashing because of so many donations, and had to change servers. Within 24 hours, the fundraising target had been surpassed, with a total of €19,413 accumulated in donations of between €1 and €500. ‘Of every 40 attempts,’ reported a 15-M member based in Seville, ‘only one managed to make a successful donation.’

Rato and his colleagues will now have to stand trial, and the success of the fundraising effort has encouraged dozens of other Bankia shareholders to add their weight to the campaign. 15-M are seeking punishments of up to six years for those responsible for the bank’s demise, and preventive custody and an embargo on their assets in the meantime. In the pre-internet days, it would have taken months or years to raise the money to pursue such a case, but as one 15-M member remarked to Spain’s national TV station, with the power of crowdfunding, ‘fear has changed sides in the battle between those at the top and those at the bottom.’

by Mark Weston | Jun 27, 2011 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia

Yesterday’s El País carried what to me was an extraordinary story about repossessions of Spanish homes. The recession has seen the number of repossessions in Spain rising to 100,000 per year, but far from suffering for making dumb loans, the country’s mortgage laws allow banks to profit from their clients’ failure to pay.

Repossession policy dictates that if a propert has to be handed over to a bank because its owner cannot keep up with mortgage payments, the bank must endeavour to sell it at auction, and use the proceeds to reduce the amount owed. In the current, stagnant environment, however, nobody is buying, even at repossession auctions, and much of what is on offer goes unsold. Such an eventuality does not perturb the banks, however – indeed, they are probably delighted not to sell – for in the event that a property fails to attract a buyer at auction, the bank gets to keep it for 50% of what it is adjudged to be worth.

Let us say, therefore, that someone has taken out a €100,000 mortgage on a house which at the time the bank judged to be worth €100,000 (many banks, of course, made 100% loans during the boom), and that after paying, say, €10,000 plus interest of that loan the debtor loses his job – not uncommon in a country with 23% unemployment – and can no longer make his monthly payments. The debtor now owes €90,000. The bank tries to sell the house at auction, with a reserve of €75,000 (the Bank of Spain says official house prices have fallen 17%, and the bank knocks off a bit extra to make it look like it is keen to sell). Nobody is interested. The house goes unsold. The bank acquires the house for €41,500 (50% of the official value of €83,000), and the debtor, who is now homeless and jobless, still owes it €48,500, plus interest.

It won’t have escaped your notice that this is a remarkably good deal for the bank. First, it received €10,000 plus plenty of interest – let’s estimate a further €10,000 – from the hapless debtor before he lost his job. Second, it is still owed nearly €50,000 plus interest. And third, it has acquired a house worth perhaps €60,000 (if we ignore the overoptimistic official figures) for just over $40,000. Even if the debtor now does the sensible thing and tells the bank where it can put the rest of the debt, therefore, the bank will have lost just 20% of the loan. Most debtors, however, will not be so bold, and will attempt to pay back the rest of the loan for fear of losing their hard-won creditworthiness. In the latter cases, the bank will have made a profit on the original €100,000 loan of €20,000 plus several additional tens of thousands in interest, so unless significantly more than half of debtors tell the bank where to go it cannot lose on these deals.

Of course, the above example is theoretical and the actual figures are likely to vary somewhat – the bank might sell the house for €70,000, adding another ten grand to its haul, and there are costs of selling to account for too. But unless I have miscalculated it does not seem too far-fetched. Under the current policy, banks benefit by making bad loans. Since most people will try to pay back the loan even though they no longer own their property, banks can easily withstand a few bad debtors, and it is not surprising in an industry where profit rules that their vetting policy is less than rigorous. A couple of commentators in the El País article recommend raising the 50% of the value at which the bank acquires the property to 70% – this would seem a bare minimum to avoid the moral hazard created by the current law. The protesters in the 15-M movement rightly blame the banks for causing the housing crisis, but where policy puts them in a no-lose situation it is inevitable that many will take advantage.

by Mark Weston | Dec 7, 2010 | Europe and Central Asia, Off topic

If you had ever planned an aerial invasion of Spain, last Friday would have been a good day to do it. For on that day, unannounced, Spain’s air traffic controllers decided to go on strike. At 5pm, all three hundred of those on duty called in sick. Five hundred flights were grounded; the skies remained empty for hours. Nobody in the government, the air force or the media had any prior warning. Nor did any of the 600,000 passengers who had to spend the bank holiday weekend (the most important in the Spanish calendar) sleeping on crowded airport floors with no food, no prospects of flight, and no information.

Spain’s air traffic controllers are among the least productive in Europe. The hourly cost of employing them is higher than in any other European country, and their annual salary, for which they work 32 hours per week, is €200,000. The wildcat strike was called because that salary has come down in the past year, bringing it closer to, but still higher than the European average, and because a new law prevents them from counting as working time all the many sick days they take (each controller averaged more than a day per month last summer).

Spain, as you may have noticed, is in the throes of a terrible recession (20% unemployment, frequent talk of IMF bailouts, no real sign of any let-up). Tourism is one of its biggest industries. The strike is likely to cost an economy already on its knees 400 million euros in lost revenue. And for a few hours on Friday until the army stepped in, the country’s skies were unpoliced.

The air traffic controllers nevertheless decided that this was an opportune time to take action. This now looks like a catastrophic miscalculation. Those who are struggling to feed their families are not delighted by the idea that a group earning in one year what the average Spaniard earns in ten think they are entitled to a pay increase. That that increase would come out of public funds (the industry is state-owned) when the country may be on the verge of bankruptcy does not add to the strikers’ popularity.

Fortunately, this tale of myopic greed has a happy ending. On Friday night the government declared a “state of alarm.” This placed air traffic controllers under temporary military supervision, effectively making them military personnel. If they do not perform their duties, therefore, they will be subject to the same penalties a soldier would face for disobedience. This can mean up to six years in prison. Within hours of the announcement of the state of alarm, the strike was over, as the spooked wildcats scurried back to their watchtowers. Disciplinary proceedings against them have already been opened, and the government seems determined to follow through with its threat. Hundreds of pampered air traffic controllers now face unemployment at best, imprisonment at worst. For the industry as a whole, privatisation beckons. The Spaniards I have spoken to, meanwhile, are pleased to see the spoilt brats getting their comeuppance. Many are no doubt wondering if the state of alarm can be extended to bankers.