by David Steven | Dec 15, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity

A while ago, a few beers drunk, I became embroiled in speculating about decidedly unconventional ways of controlling greenhouse gases. Two ideas lodged firmly enough in my memory to last until the next day: burning sheep and burying trees.

Now before any of you vegans start with the hate mail, I want to stress that this was a thought experiment. No lamb was subjected to even the lightest singeing. But you understand the logic…wouldn’t it be good if you had a machine that could range around marginal land (rather than attractive pasture) under its own steam, all the while turning biomass into a high-octane biofuel?

Use a sheep and you’d get wool as an additional by-product. Plus the UK proved the concept when it incinerated most of the cows in the country when BSE hit…

Tree burying seemed like a cheap and easy way of carbon sequestration (with technology that works today, rather than in twenty years’ time). Grow trees as fast as possible. Then throw them down a disused coal mine. Repeat ad nauseam. Of course, you’d get methane released as the trees rotted – but surely there’d be a way of sealing that in or tapping it off.

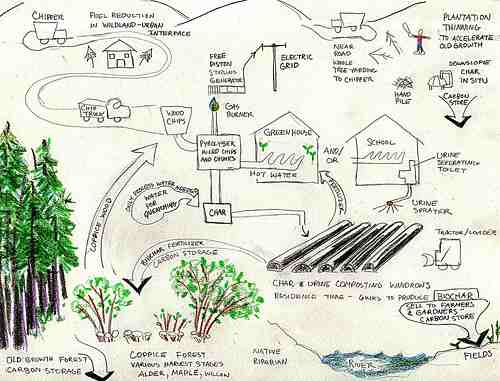

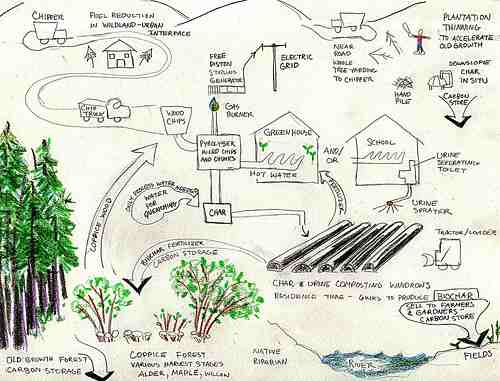

It turns out that tree burying isn’t such a bonkers idea – it’s just you need to bury charcoal instead. Or so I discovered today at a post-Poznan washup (hosted by IES, Globe and European Economic and Social Committee), where the best presentation of the day was from Craig Sams on biochar.

Craig founded the Whole Earth organic food brand and Green and Black‘s organic chocolate (both of which he has since sold). He’s now pushing charcoal as a low-tech solution to the climate change problem, working with Daniel Morrell, founder of the Carbon Neutral Company.

Craig’s pitch is as follows (for more detail see this white paper from the International Biochar Initiative):

- The world’s soil has lost a colossal amount of carbon due to centuries of intensive agriculture (accounting for about half of the current stock of atmospheric greenhouse gases).

- You can take biomass (fast growing crops that you grow specially, coppiced trees or even the crud that gathers on the forest floor), and turn it into charcoal using pyrolysis (you get some energy too).

- The char can then be added to soil (either in forests or on agricultural land), where it enriches it, reduces the need for nitrate fertilisers, and stores large quantities of carbon for the long-term (all, potentially, achieved through a myriad of grassroots schemes).

Craig dropped an eye-popping stat into his presentation. If all available land were devoted to biochar for just one year, then enough carbon could be sequestered to take atmospheric concentrations back to pre-industrial levels. Admittedly, we’d all starve for 365 days – but it shows the potential.

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Dec 12, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity, Europe and Central Asia

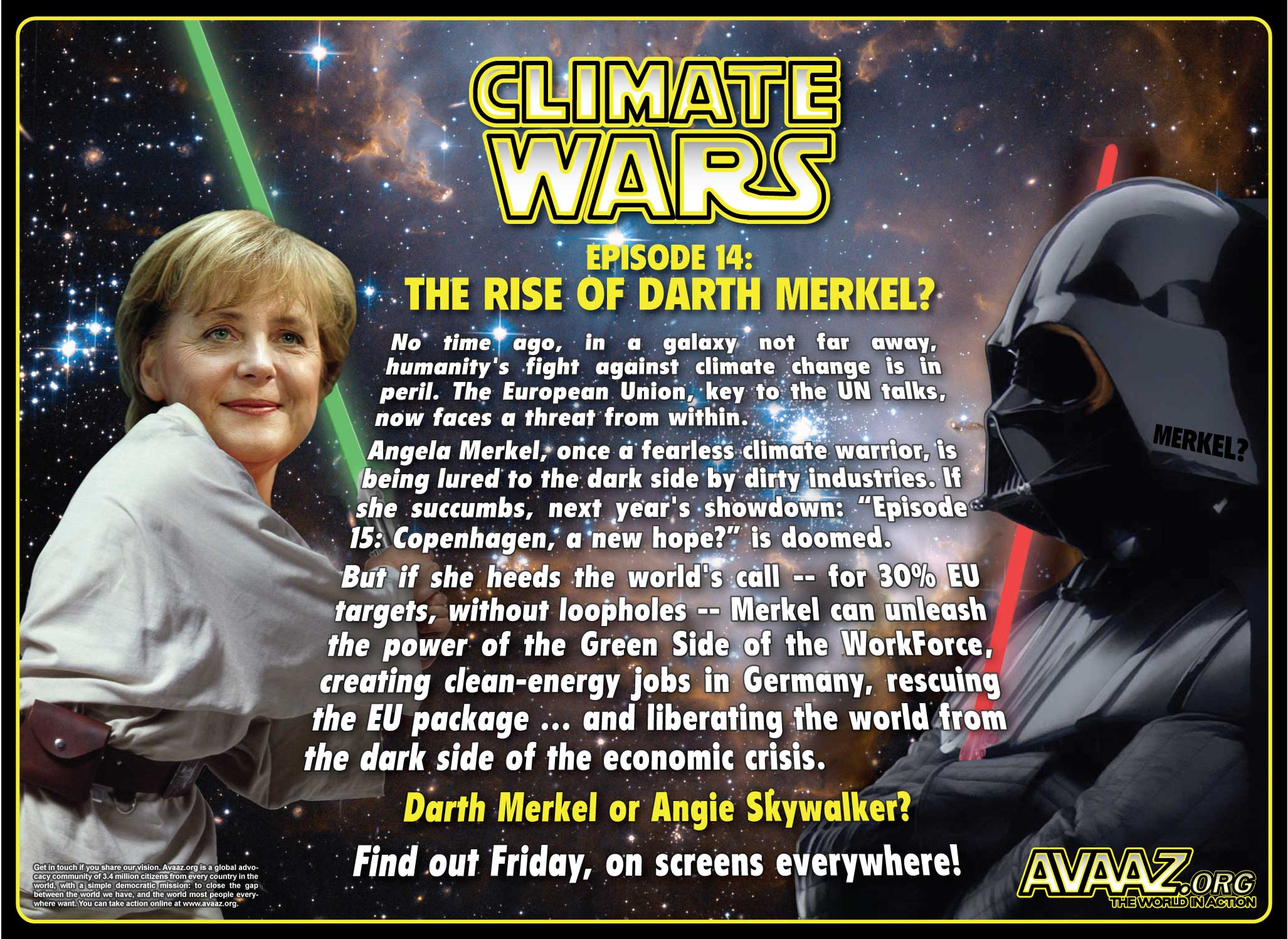

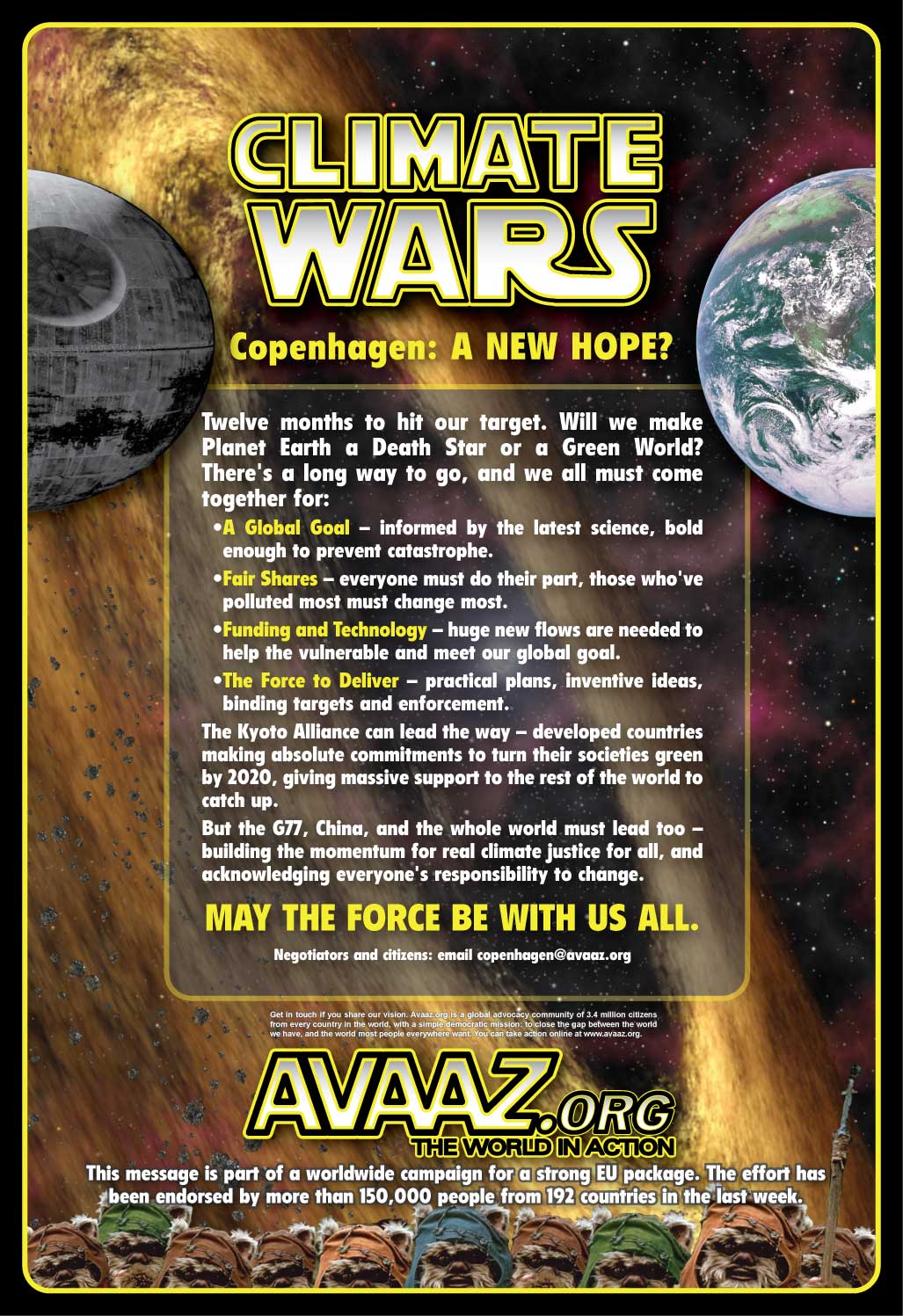

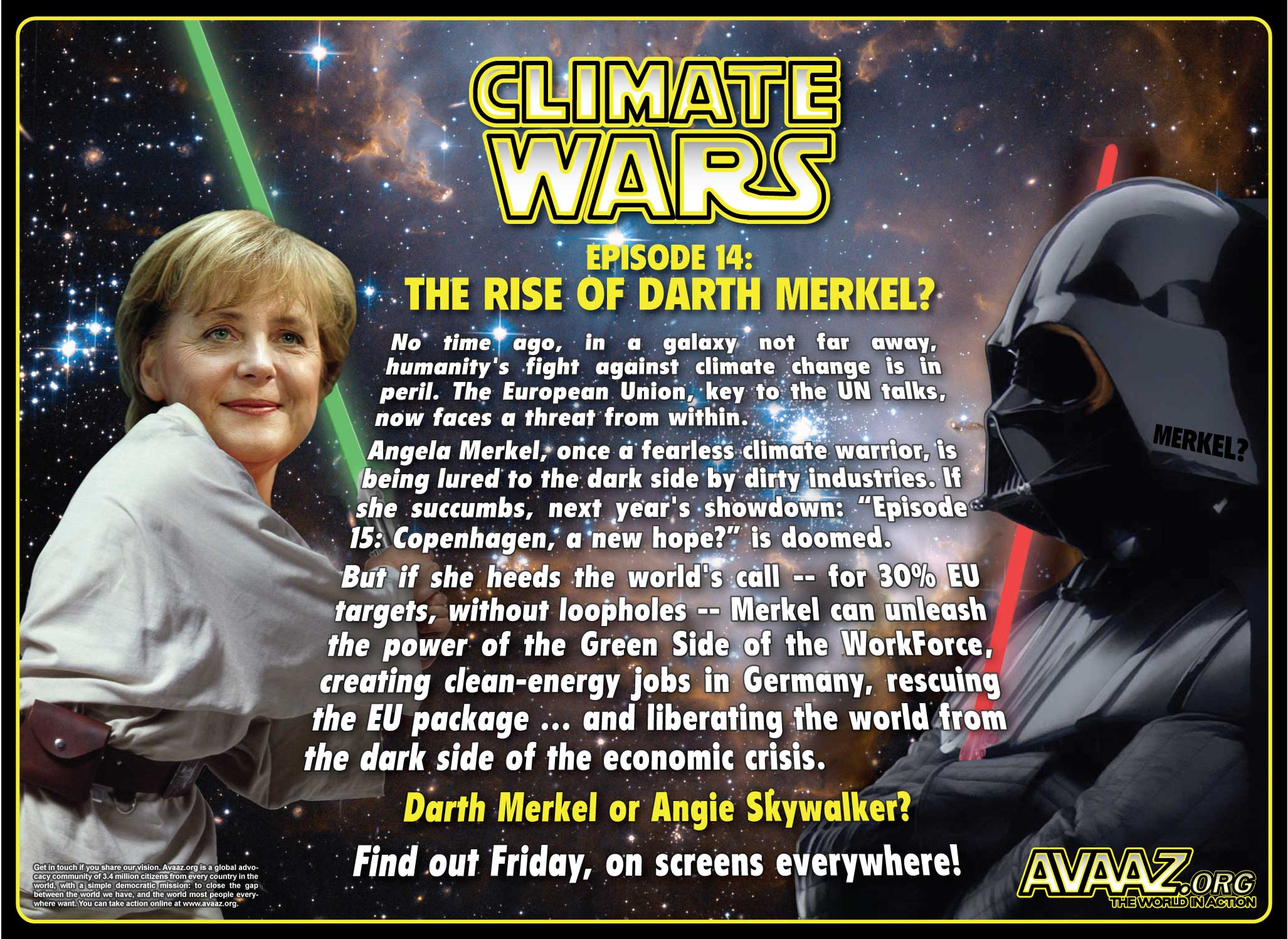

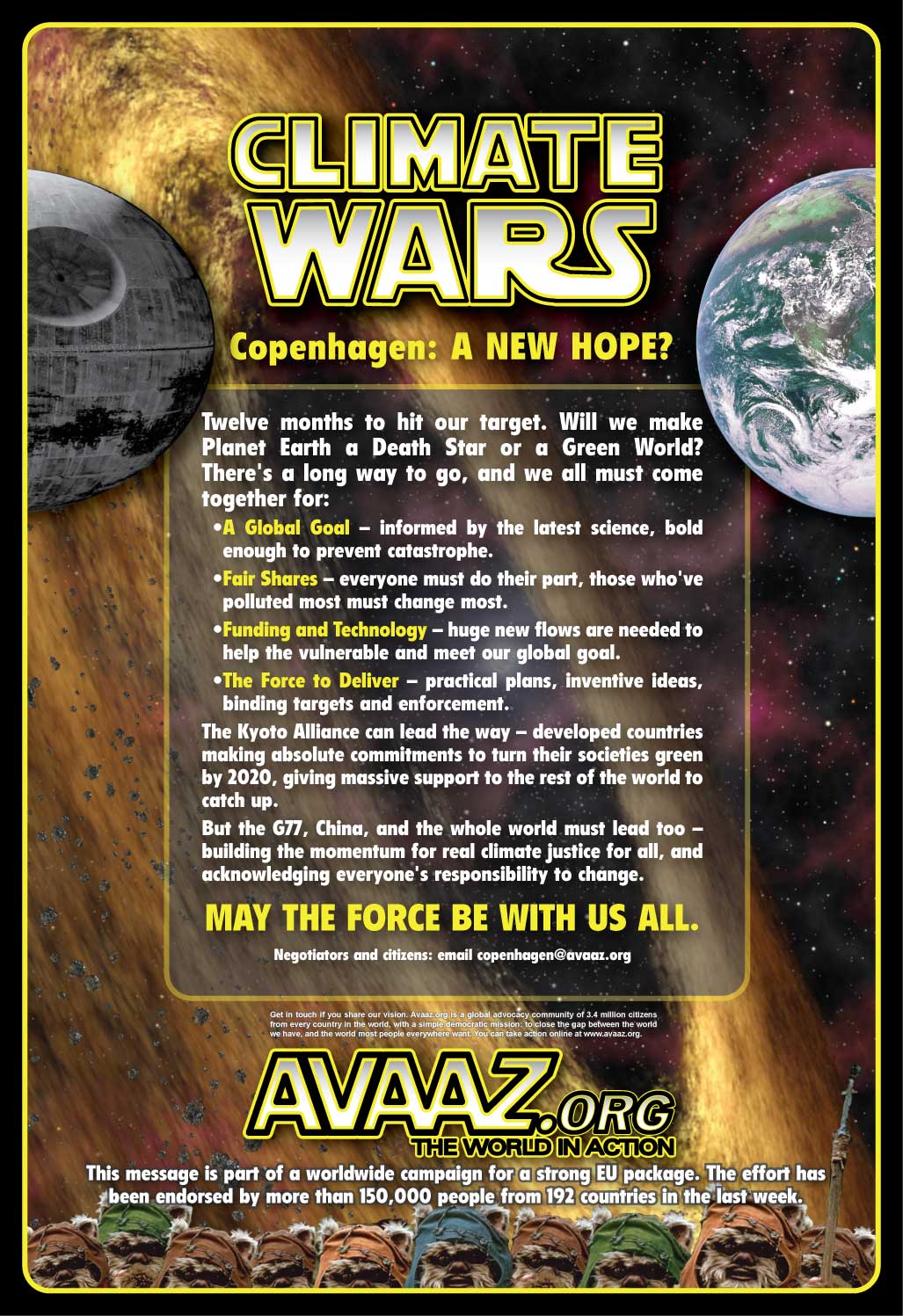

More top notch advocacy from Avaaz.org, who are busy making mischief at the UN climate negotiations in Poznan with this splash in the conference newspaper. Avaaz are, like right-thinking people everywhere, less than happy about the EU’s interesting strategic decision to set an ambitious 2020 emissions reduction target in order to breathe life into the climate negotiations, and then… er… enter into intra-EU negotiations to backtrack on said target during the UN climate negotiation. You couldn’t make it up.

Avaaz also commissioned some polling from YouGov during the summit, intended to put pressure on the Germans, together with the Poles and Italians (who are also backsliding). Key findings: 85% of Germans think that Germany should show leadership in securing a strong climate agreement for the EU despite the economic downturn, plus 74% of Poles and 87% of Italians.

All of which is good news, needless to say, but not nearly as enchanting as the fact that Avaaz supporters are cast in the role of ewoks (see below)…

by David Steven | Dec 6, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity

The climate talks in Poznan were never going to be a dazzling success – but, away from the nitty gritty of text, three big things need to happen for a reasonable result to be achieved.

First, the Europeans have to set out their stall (again) – but this time show that they can match aspirational targets with domestic delivery. Second, the Americans need to be begin the process of re-engaging: some sense has to emerge of what the post-Bush era should look like. And finally, we desperately need the emerging economies to begin to talk openly about where they think they fit into climate control. What does a good deal look like for them – not just between now and 2020, but over the next generation or two?

Unfortunately, the news doesn’t look good on any of these fronts. The Europeans – staggeringly, unbelievably – have allowed squabbles over their own climate package to spill over into the broader international negotiation. How’s this for showing united leadership to the rest of the world?

French President Nicolas Sarkozy failed to end deadlock with ex-communist European Union states on an EU climate package on Saturday but predicted a deal would be reached by a December 11-12 summit.

“Things are moving in a good way … I am convinced we will arrive at a positive conclusion,” Sarkozy, whose country holds the rotating EU presidency, said after meeting Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk and eight other east European leaders.

Poland, which relies on high-polluting coal for more than 90 percent of its electricity, has threatened to veto an EU plan to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent below 1990 levels by 2020 unless Warsaw wins fossil fuel concessions.

“There is still a lot of work ahead of us” before the summit, Tusk said after the talks in the Polish port of Gdansk.

Poland argues it needs until 2020 to curb carbon emissions, for example by using more efficient boilers and carbon-scrubbing equipment and possibly building its first nuclear plant.

Tusk said Sarkozy and the EU Commission agreed to extend a period limiting mandatory purchases of greenhouse gas emissions permits for east European coal plants, in an offer which would need the backing of all EU leaders.

And Tusk hinted at a willingness to compromise at the summit. “At the very end, maybe at the very last minute, we may decide this is a solution we may accept,” Tusk said.

Meanwhile, the American negotiating team appear not to have even talked to the Obama transition team (h/t Andrew Kneale). If true, this is worse than stupid:

As I’m sure the Obama Administration transition team is aware, Poznan, Poland is currently hosting a very important UN-sponsored climate change conference. At stake is nothing less than the next round of emissions reduction commitments (a Kyoto successor) — which Barack Obama has said he wants the U.S. to participate in.

If they haven’t already, the Obama folks need to make contact with the U.S. delegation in Poznan immediately. One would think that the U.S. Del. would take the initiative itself, but I’m getting word that they feel that the ball is in Obama’s court.

Apparently, current U.S. delegation members — mostly career people with honorable intentions and a willingness to continue to serve (with some notable exceptions) — are waiting for the call. This is no time to fight about protocol, or who is supposed to call who. It’s time to start turning the ship around.

Things are going to slow down for the weekend and then pick up again on Tuesday. The framework that comes out of this week can still be quite ambitious and, at the same time, workable in the U.S. and in the Senate. The Obama people have from now until Tuesday to make their goals for Poznan clear, but the sooner, the better.

Finally, as I posted a few days ago, developing countries seem resistant to even talking about the long-term – even though they have the most to lose through lots of itsy bitsy short term deals…

Happy days.

(For more, see all GD’s Poznan posts, our broader coverage on climate, follow the #poznan feed on Twitter or check out benkamorvan’s list of Poznan related blogs and other sites.)

by David Steven | Dec 5, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity

What’s striking about the climate talks in Poznan is that (some) developed countries want a long-term goal, while (most) developing countries are only prepared to talk about the next few years. Here’s Xinhua:

The developed countries are seeking to set up a shared vision on long-term goal for emission cuts, saying that such a goal will set the direction for future actions.

Some industrialized countries believe that a 50-percent cut of emissions against the 1990 level by 2050 is necessary for the goal of preventing rising temperatures.

The developing nations, however, rejected such a global goal at this stage, arguing that such a vision is not feasible since there are no concrete plans for providing finance and technology required by the developing countries.

But really, it should be the other way round. Given that:

- A limited emissions ‘cake’ is available between now and, say, 2050 (assuming an eventual attempt to stablize atmospheric GHG concentrations).

- And that rich countries are consuming disportionate shares of that cake on every year.

- Then poor countries are likely to receive a smaller slice the longer it takes to start negotiating a comprehensive allocation.

Short term deals (Kyoto, Kyoto 2, Kyoto 3 etc) suit developed countries. A full-term deal would allow developing countries to understand then try and protect their long-term interests…

by Alex Evans | Dec 5, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity

Relatively little media coverage so far on the UN climate talks currently underway in Poznan – but that’s not to say that nothing interesting is happening there.

Item 1 is that China and India have come out arguing that Obama’s proposed 2020 emissions reduction (namely, to get US emissions back to 1990 levels by that date – more details here) is insufficient. He Jiankun, a Chinese delegate, was quoted in Reuters as saying that “It’s more ambitious than President Bush but it is not enough to achieve the urgent, long-term goal of greenhouse gas reductions”.

Given that the IPCC says that stabilising at 450 parts per million of CO2 equivalent (the maximum level on which we still have a better than even chance of limiting warming to 2 degrees C) probably requires developed countries to reduce their emissions by 25-40% below 1990 levels by 2020, you can see where the Chinese and the Indians are coming from.

But as David pointed out when he and I were debating this a couple of weeks ago, the US’s emissions have gone through the roof under Bush: even the very modest target proposed by Obama is going to be a massive stretch for them. Expect this one to run and run.

Item 2: Brazil is reportedly sidling up to per capita convergence as the formula for sharing out a global emissions budget, at least if you believe this report in Business Green yesterday, which says:

Brazil reportedly put the finishing touches to proposals apparently based on the contraction and convergence principle that would see countries agree to per-capita emission reduction targets. Under the proposals, emission targets would be set on a per-head-of population basis, meaning that developing economies with low-carbon emissions per capita such as China would face less-demanding targets, while those countries with the highest level of emissions per person would have to deliver the deepest cuts.

Fascinating if true, but they don’t cite their source, so I’m regarding as tentative until I hear it from another source or two.

Item 3, meanwhile, is that in a workshop on “shared visions” for the future on Tuesday, China made some tentative steps towards setting out its stall on how it would want an emissions budget to be shared out. This is very interesting, as China’s the most important of the handful of developing countries for whom straight per capita convergence wouldn’t be advantageous – as its per capita emissions have (just in the last few months) gone over the global average per capita level, meaning that even immediate convergence at equal per capita shares to the atmosphere would leave them with no surplus permits to sell. What then is China proposing? The Worldwatch Institute wrote it up like this:

China, citing the equity language of Article 3, mentioned the need for eventual “global per-capita emissions convergence” – the idea that, at some point in the future, all countries in the world should have similar per-capita emissions as a matter of climate equity. But this concept did not pick up momentum, at least not in the workshop.

That had me sitting bolt upright in my chair and reaching for the phone to ask people in Poznan if it was really true. The answer back: not quite. In fact, what China seems to have been proposing is a system of per capita convergence in cumulative emissions – i.e. taking into account historical responsibility for past emissions, as well as current emissions – which would clearly be much more advantageous to it, given how much later China industrialised than (say) Britain (for whom historical responsibility based allocations of emissions permits would be rather, ahem, challenging).

But the real significance here is less the specific formula that China proposed (more details needed – if you were in the workshop, please drop me an email), and more the fact that China may now be starting to engage in a conversation about the formula that might be used to share out a global emissions budget. Up to now, discussion of stabilisation targets for greenhouse gas levels in the air has been off the table – in large part due to Chinese unwillingness to talk about how the emission budget implied would then be shared out. If that’s changing, then the future just got a little more hopeful.