The Vickys: can you be paternalist without being patronising?

Two news stories caught my eye this weekend. Firstly, the British government wants to launch a voucher scheme so every parent can take parenting classes from a range of providers. One of them is called the Parenting Gym, and is owned by Octavius Black, the millionaire school-chum of David Cameron’s, who made his fortune through Mind Gym, a corporate well-being consultancy.

Two news stories caught my eye this weekend. Firstly, the British government wants to launch a voucher scheme so every parent can take parenting classes from a range of providers. One of them is called the Parenting Gym, and is owned by Octavius Black, the millionaire school-chum of David Cameron’s, who made his fortune through Mind Gym, a corporate well-being consultancy.

The other story was that the Templeton Foundation has given a multi-million-pound grant to Birmingham University to set up a Jubilee Values and Character Centre. The press release says:

How does the power of good character transform and shape the future of society? What would be the wider social, cultural and moral impact of a more grateful Britain? What personal virtues should ground public service? How can fostering character traits like hope and optimism be help working towards a better British society? The Centre will initiate a national consultation on a proposed curriculum policy for character building in schools, and will run a 10-year project at Birmingham called ‘Gratitude Britain’.

These are the two latest trumpet-blasts from a movement which has been dubbed the New Paternalism. The phrase originally appeared from Nudge psychologists like Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, who call their nudge policy interventions ‘libertarian paternalism’. They want to nudge people in pro-social directions without them realising it (hence it’s ‘libertarian’ – because the citizens are so dumb they don’t realise they’re being guided).

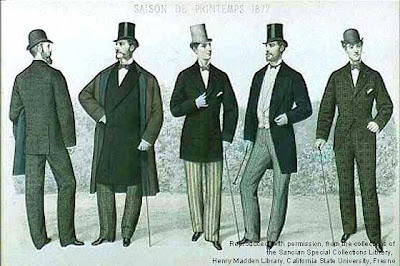

But there are other New Paternalists who are much bolder. They want to instil good values in the citizenry, create good habits, foster good character. They are similar to Victorian paternalists like Matthew Arnold, but they take his lofty Hellenic philosophy and try to put it on a firm evidence base, to create a science of resilience, optimism and other ‘character strengths’.

I call this movement the Vickys, after the tribe in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. It’s a steam-punk novel about a future society that has fragmented into a collection of tribes or ‘phyles’, each with their own culture and moral code – including a Nation of Islam tribe, a neo-Confucian tribe, and the Vickys, who are cyber-engineers and who follow Victorian customs. Basically, success in this society is all about what phyle has accepted you. Your character depends on your moral culture. The book tells the story of how the leader of the Vickys hires a nano-engineer to code an interactive ‘gentleman’s primer’ to cultivate the character of his niece – except it gets stolen and discovered by a street orphan, who subsequently rises to the top of her society.

I call this movement the Vickys, after the tribe in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age. It’s a steam-punk novel about a future society that has fragmented into a collection of tribes or ‘phyles’, each with their own culture and moral code – including a Nation of Islam tribe, a neo-Confucian tribe, and the Vickys, who are cyber-engineers and who follow Victorian customs. Basically, success in this society is all about what phyle has accepted you. Your character depends on your moral culture. The book tells the story of how the leader of the Vickys hires a nano-engineer to code an interactive ‘gentleman’s primer’ to cultivate the character of his niece – except it gets stolen and discovered by a street orphan, who subsequently rises to the top of her society.

The Vickys include Martin Seligman and the Positive Psychologists, who have got enormous backing from Templeton for their research into character strengths and resilience training, and who launched a $125 million course in resilience-training for the US Army. Like Stephenson’s Vickys, they want to create a computer-automated course in moral education – an app for character. The Vickys also include include self-control psychologists like Roy Baumeister, and champions of ‘social and moral capital’ like Jonathan Haidt and Robert Puttnam.

In the UK, the Vickys include Wellington headmaster Anthony Seldon and his new colleague, the young former policy advisor James O’Shaughnessy, who has gone back to Wellington to set up a chain of Wellington academies; Matthew Taylor of the RSA; Matthew Grist and Jen Lexmond of Demos; the Young Foundation; David Goodhart of Prospect Magazine; Danny Kruger, another former Tory advisor who now runs a charity for former prison inmates; Lord Richard Layard of the LSE; and, more speculatively, Alain de Botton, whose more recent writings have called for a shift beyond liberalism and back to a more interventionist paternalism.

Anthony Seldon described the New Paternalist ethos in the Telegraph this week. He wrote:

Character, and specifically its neglect, is the number one issue of our age. A society that is not grounded in deep values, that doesn’t know who its heroes are and that lacks a commitment to the common good, is one that is failing. Such we have become… The riots in British cities in August 2011 were the catalyst for the creation [of the new Jubilee Centre for Character and Values]. As the fires subsided, a call was heard across the nation for a renewed emphasis on communal values and ethical teaching, which would discourage such events happening again. It is an indictment of us all that such a centre should ever need to have been established…The development of a sense of gratitude among people in Britain will be at the heart of the work. The character strengths it will advocate are self-restraint, hard work, resilience, optimism, courage, generosity, modesty, empathy, kindness and good manners. Old-fashioned values, maybe. Some will sneer, and ridicule them as middle class or “public school”. But these are eternal values, as advocated by Aristotle and countless thinkers since.

I am interested in this movement, and attracted to some aspects of it. My new book is about the contemporary fusion of virtue ethics with empirical psychology, and how this new fusion is being spread by public policy in schools, the army and beyond to foster character, resilience, eudaimonia and other such ideals. I got into the scene when Cognitive Behavioural Therapy helped me overcome depression in my early 20s, and I then found out how much CBT owed to ancient Greek philosophy. I’m a huge fan of Greek philosophy and its practical therapeutic use today, so a part of me loves the renaissance of virtue ethics in modern policy.

But we have to be aware of the ideological and political context of these efforts in mass character education. It can all too easily seem like rich people telling poor people to buck up and be a bit more moral. It can ignore the economic and environmental context and how that dynamically feeds into character. I’m not saying character is entirely caused by economic context. But it’s certainly a factor – Aristotle himself knew that. He insisted eudaimonia was as much made up of external factors like wealth and the kind of society you live in. If you’re too poor or your society is too unequal, he warned, it would be very difficult for you to achieve eudaimonia or for your society to find the ‘common good’. (more…)