by David Steven | Mar 19, 2010 | Africa, Economics and development

You see plenty of reports from development agencies castigating development countries for one reason or another, but the boot is much less often on the other foot.

Interesting then to see this 2008 review (huge pdf download) from Nigeria’s National Planning Commission, which sets out to analyse ‘the volume and quality of Official Development Assistance to Nigeria between 1999 and 2007.’

During this time, $6bn of aid has been spent in Nigeria, almost all of it spent by donors themselves, rather than being rooted through the government’s budget. The Planning Commission’s first job, therefore, was to try and work out who had spent what.

So it sent a template to donors asking for information on what they’d spent and where:

Of all the agencies, USAID was the only agency able to provide almost all the requested information with a little delay. EU was also able to meet most of our requirement, only after about three months delay…

CIDA’s [Canada] claimed disbursement did not tally with what they had actually spent…[It] refused to supply more information when asked [to]…

DFID is another donor that could not account for all its activities. When asked to provide information on the sectors and states DFID is operating in, it simply wrote saying ‘we do not require our programme managers to collect expenditure on a state-by-state basis.’…

JICA [Japan]…did not cooperate at all despite our many efforts to get JICA to collaborate with us.

The UN system was also only ‘partially cooperative’. UNICEF did not provide a breakdown of its health spending, for example (nor did DFID or CIDA). “We do not know exactly what [this] money was spent on,” the report notes. The Chinese government was also asked for data – but the review does not tell us what its response was (read into that what you will).

Donors should be much more transparent accountable for their activities, the Planning Commission concludes, while the Nigerian government “needs to offer clearer and more effective leadership to her development partners both in terms of how and where to operate.”

It lauds the example of Kano and Ondo states. They are robust in their response to ‘intruder donors’ who operate outside a framework established by the state government. That allows leaders to set, and be accountable for, their own development priorities.

Update: Of course, Nigeria’s own statistics are often woefully inadequate, whether at national or at state level. Recently, for example, Kano state has just been counting its schools:

An additional 88 senior secondary schools and 174 private schools had been ‘discovered’, while in some areas schools had disappeared: the Kano municipality had 10 less junior secondary schools than first thought.

Update II: Worth pointing out, too, that the World Bank, DFID, USAID and African Development Bank recently agreed a joint strategy for Nigeria – bringing 80% of Nigeria’s development assistance under a single strategic umbrella. Somewhat oddly though, it cannot easily be found on any of the donors’ websites. There’s a copy here though.

I wonder if the donors will now move towards a single online platform to show what they’re spending, where, and what results it’s achieving… and, also, how effectively their joint approach is proving (the Bank and DFID have had a joint strategy for some years now) at reducing overhead for Nigerian government and non-government partners.

by David Steven | Nov 10, 2009 | Africa

Wrong on so many levels:

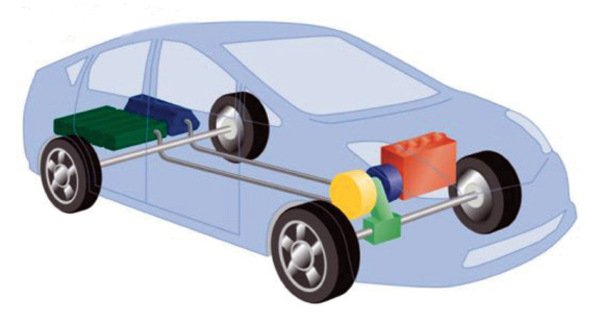

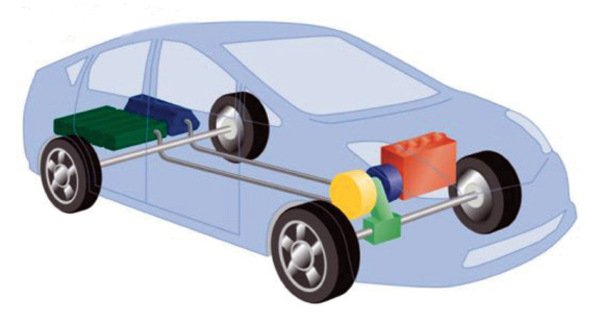

The National Automotive Council (NAC) is collaborating with the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) to fine-tune the concept for a made-in-Nigeria car…

“Once the bill is passed and the budget proposal before the National Assembly is passed, we will come up with the concept of the made-in-Nigeria car with a road show,” [Aminu Jalal, the Director General of the Council] said.

The automobile needs of Nigeria can only be met when all the stakeholders in the industry work towards meeting international standard, Mr. Jalal said, adding that the agency’s main focus is to encourage local manufacture of auto components. The council is equally wooing Nigerians in the Diaspora, who have indicated interest in investing in the manufacturing of auto components and ancillaries.

Unlike other emerging economies, Nigeria is yet to witness a revolution in its automobile industrial sector. As at today, the dream to have a made-in-Nigeria car has remained exactly that – a dream.

Apparently, “the absence of local source of raw materials” has delayed progress to date. From the look of early designs, this obstacle has been solved through judicious use of Lego. Presumably, the full power of the UN system will now be thrown behind the project.

by Mark Weston | Oct 12, 2009 | Africa, Conflict and security, Economics and development

While researching my upcoming book on the world’s poorest countries last week, I came across David Keen’s ‘Conflict and Collusion in Sierra Leone,’ an analysis of the causes of the world’s poorest country’s vicious 1990s civil war. What struck me most was the similarity between what I read of the conditions in Sierra Leone before war erupted and what I heard on a recent trip to Nigeria of the conditions prevailing there.

The parallels are remarkable. Burgeoning youth population? Check. Intense competition for services and economic opportunities? Check. Collapsed education system that fails the young? Check. Dependence on a single valuable natural resource? Check (diamonds in Sierra Leone, oil in Nigeria). Neglect of other economic activities like agriculture? Check. Catastrophic lack of jobs? Check.

The result of all these fundamental problems in Nigeria, as in Sierra Leone, is a youth population that cannot establish itself. Denied employment, young people cannot leave their parents’ homes, marry, or start families. Their reliance on the older generation deprives them of the latter’s respect. Their resentment of their elders, who benefited from a better education, faced weaker competition for jobs, and have control over the country’s economy, is acute. The corruption and decadence of those in power and their lack of interest in young people’s demands further fan the flames (both David Keen writing on Sierra Leone and several Nigerians I spoke to said that wealth, no matter how dishonestly acquired, had become society’s’ overriding goal – as a young woman in Lagos lamented, “nobody asks how you got rich”).

In Sierra Leone, young people eventually took out their frustrations with extreme violence. Among their main targets were village chiefs and other figures of authority. When the Revolutionary United Front invaded Freetown in January 1999, its young rebel soldiers sought out and dealt out horrific punishments to journalists and writers who had criticised them and shown them disrespect. Many young Nigerians also bemoan the lack of respect they receive from the older generation, who dominate the country’s institutions.

(more…)

by Mark Weston | Jul 27, 2009 | Africa, Conflict and security

The BBC reports that the weekend’s violence in the city of Bauchi has spread to other parts of northern Nigeria, including the sleepy northeastern town of Maiduguri and Wudil, a town near Kano. A BBC reporter counted over 100 bodies in Bauchi.

Blame has been placed on a militant Islamist group called Boko Haram, an organisation made up mostly of former university students who are opposed to the westernisation of education. Apparently (although nothing is clear), some of the group’s leaders were arrested, so their cadets took to the streets with guns to secure their release.

Most of northern Nigeria is under sharia law. On a trip there earlier this month for the Next Generation Nigeria project, I met sharia leaders in Kano, the north’s biggest city. They told me that resistance to western education had historic roots, as it was seen as an attempt by southern Christians, who had been educated by the British colonisers, to spread their religion to the Muslim north.

Only in recent years has this resistance weakened, and many parents are now very keen for their children to attend western schools. Trouble is, there aren’t enough places for the burgeoning numbers of children, so in many areas Islamic schools remain the only option. State governments are encouraging these schools to teach secular subjects like English and maths as well as Kuranic studies and Arabic.

The religious leaders I spoke to were generally fine with this, but it seems not all their peers are of the same opinion. Mohammed Yusuf, the leader of Boko Haram, has said western education is forbidden, and recruited students to advance his arguments. Given how bad Nigeria’s schools and universities are, and how slim graduates’ prospects of getting a decent job when they leave, the recruitment drive probably isn’t difficult.

If Yusuf’s campaign is successful, it will be a blow to northern Nigeria’s development prospects. Although Islamic schools may do a good job of inculcating values and morality, for the vast majority of their alumni what they teach is of no value at all to their careers. I asked a sharia leader how Arabic and Kuranic studies help students find jobs, and he replied that they could work as teachers in such schools or as imams. This would be fine if everybody could become an imam or a teacher, I said, but then there wouldn’t be any congregation or students. He smiled patiently, and said that the rest would work in the fields or hawking in the street. In the north, as in the country as a whole, too many leaders benefit from the status quo to concern themselves with progress.