by David Steven | Sep 22, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Europe and Central Asia

Today, Ban-Ki Moon, worried by fading prospects for a climate deal at Copenhagen, will try and knock heads (of state) together at his Summit on Climate Change. Here’s the list of speakers:

H.E. Mr. Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations

Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, Chair, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

H.E. Mr. Barack Obama, President of the United States of America

H.E. Mr. Mohamed Nasheed, President of the Republic of Maldives

H.E. Mr. Hu Jintao, President of the Peoples Republic of China

H.E. Mr. Yukio Hatoyama, Prime Minister of Japan

H.E. Mr. Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda

H.E. Mr. Fredrik Reinfeldt, Prime Minister of Sweden

H.E. Mr. Óscar Arias Sánchez, President of Costa Rica

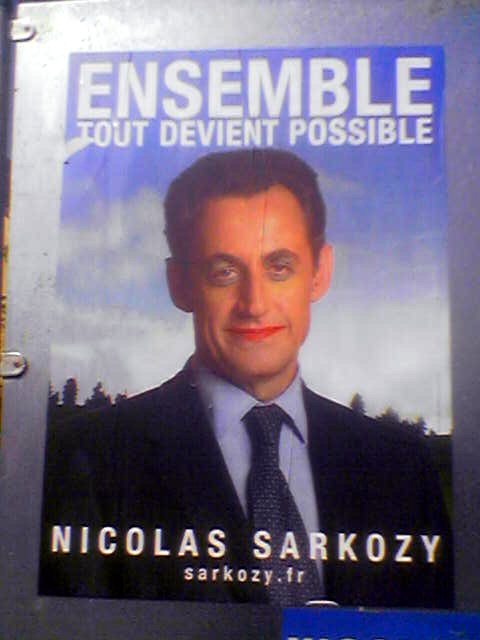

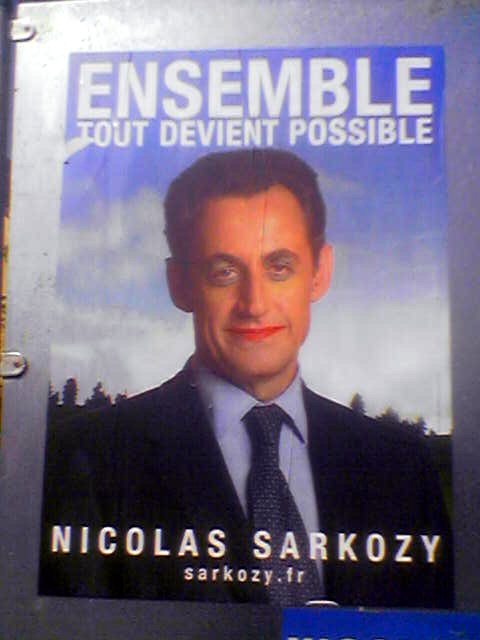

H.E. Mr. Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France

Professor Wangari Muta Maathai, Founder, Green Belt Movement, Kenya (Civil Society)

Ms. Yugratna Srivastava, Asia-Pacific UNEP/TUNZA Junior-Board representative, India, age 13 (Youth)

H.E. Mr. Tillman Joseph Thomas, Prime Minister of Grenada

H.E. Mr. Ahmad Babiker Nahar , Minister of Environment and Urban Development of Sudan

H.E. Mr. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, Prime Minister of Denmark

It’s a pretty standard list – major powers (check), regional balance (check), soon-to-be-submerged-island-state (check), boffin (check), civil society (check), token youth (check). But then you hit the European problem. The Swedes hold the Presidency and thus speak for the EU. Rasmussen is there because he’s going to shoulder a lot of the blame if Copenhagen fails to deliver. But how on earth has Nicolas Sarkozy managed to clamber onto the platform?

It beggars belief that, just when Europeans most need to speak with a single voice, the French president is – once again – giving his ego free rein. Or have I missed something?

by Alex Evans | Sep 18, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global system

So what should we all be watching out for at next week’s G20 summit? Let’s start with the obvious stuff.

– Expect to hear lots about bankers’ bonuses, in particular from Brown, Merkel and Sarkozy. I can’t find it in me to give a crap about this issue, but doubtless it will command saturation media coverage all week. More substantive on the banking front will be the question of whether concrete proposals are advanced for hedge fund rules or financial supervision regulation – lots of noise here, but not much specificity so far.

– We’ll also hear lots of debate about when to wind down stimulus programs – which was a big issue at the EU’s preparatory summit (continentals more hawkish, but Brown edgier about turning the taps off). Goldman Sachs’s Jim O’Neill has an op-ed in the FT this morning arguing that while co-ordination was needed for starting the stimulus off, it’s less necessary to have co-ordinated exit strategies.

– The IMF and the World Bank have been doing good advocacy about the need not to forget about low income countries. Zoellick and Strauss-Kahn are both arguing that LICs have an external financing deficit of around $59bn this year (for comparison, that’s exactly half the 2008 global aid total). On the plus side, G20 members have actually delivered the $500bn they promised the IMF – which means the Fund can front up around a third of the total needed. Strauss-Kahn is also talking about a breakthrough on IMF governance reform. (Believe it when I see it.)

– We’ll hear a lot about climate, but it’s hard to see what deal the G20 is supposed to cut (especially with Ban Ki-moon’s heads-level climate summit in New York the same week). The story the media runs with will be all about pressure on the US to do more, following Japan’s announcement of a tougher 2020 emissions target, and the EU’s long-awaited finance package. (Still, Obama ain’t the problem – the real issue here, of course, is that things don’t look great in the US Senate.)

The issue on the agenda that I’m most interested in for next week, though, is trade. First, what – if anything – will the G20 say on protectionism? For all the warm words at the London Summit in April, it’s increasingly clear that most G20 countries are in breach of their commitments – right now most notably in the case of the US, whose new tire tariffs are disastrous. Dan Drezner’s take on this is worth reading (things are “very, very scary”) – but on the other hand, Alan Beattie thinks White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel may have a crafty and ultimately beneficial political calculus in mind.

On a related note, how intriguing to see US sherpa Mike Froman talking up Pittsburgh’s chances of tackling global economic imbalances (“we hope to reach agreement on a framework for balanced growth, for agreeing on how to address the imbalances that led to this crisis and on some process for holding each other accountable”). Not what I expected – but great, if he can pull it off. That said, I found myself wondering last night: is it conceivable that this is part of a messaging strategy to defend the tire tariffs? Hollow laughs all round if so.

Finally, the issue no-one’s talking about but everyone should be: the impending return of the food / fuel price spike. All these stories about oil companies finding new giant fields are so much straw in the wind. (So the new Jubilee field off Sierra Leone has 1.8bn barrels? Great: a whole twenty-one days’ global demand. Colour me thrilled.) The more fundamental point is about demand, which is picking up again in the non-OECD economies – and let’s remember that it’s in these countries that all the demand growth for oil will come between now and 2030.

The stage remains firmly set for a renewed oil supply (and hence price) crunch in the short term – and when that happens, food prices will go straight up too, as costs for transport, fertiliser and on-farm energy use race upwards and biofuels become even more competitive as a source of demand for crops. We’re already at a baseline of 1.04bn undernourished people (compared to 850m before the last food price spike) – do the maths. So my wish list for the G20?

- $6bn funding for WFP – now.

- Leave the trade round on hold, but agree emergency WTO rules against food export restrictions (like the ones that already exist in NAFTA).

- Build up a multilaterally managed emergency food stock – maybe part real, part virtual (see Feeding of the 9 Billion for full details).

- Commit to universal access to social protection systems by (say) 2015 – and lock the funding in place, now (only 20% of the world’s people currently have access to them – but these are the best-defence resilience mechanism for poor people facing price spikes, way better than price controls or economy-wide subsidies)

- Bring China and India into full IEA membership, so that they’re part of its emergency supply management mechanism.

- Start driving real inter-agency coherence by commissioning the most important multilateral agencies for scarcity issues – UN, Bank, Fund, OCHA, WFP, FAO, IEA – to produce a joint World Resources Outlook. We need the integrated analysis; we need the political momentum it will create.

- Ask Ban Ki-moon to set up a High Level Panel to look at the international institutional dimensions of climate, scarcity and development – covering not just the UN, but the entire international system. This is the bit of international system reform that both the 2004 and 2006 High Level Panels left for another day. Today is that day.

by Michael Harvey | Sep 15, 2009 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, UK

– With the anniversary of Lehman Brother’s demise, the FT recalls the events of that fateful weekend last September. The NYT has reflections of three former Lehman employees, while a Guardian roundtable asks what lessons, if any, we’ve learned from the bank’s fall. Niall Ferguson, meanwhile, rails against those who argue “if only Lehman had been saved”. He suggests:

Like the executed British admiral in Voltaire’s famous phrase, Lehman had to die pour encourager les autres – to convince the other banks that they needed injections of public capital, and to convince the legislature to approve them.

– Sticking with matters financial and economic, Der Spiegel has an interview with the head of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, on the Fund’s actions during the crisis and the potential for a new role for the institution going forward. Former MPC member, David Blanchflower, meanwhile, offers a telling insight into the inner workings of the Bank of England’s decision-making as financial meltdown ensued.

– Elsewhere, the WSJ reports on President Sarkozy’s call to broaden indicators of economic performance and social progress beyond traditional GDP, following the findings of the Stiglitz Commission. Richard Layard, expert on the economics of happiness, offers his take here, arguing that “[w]e desparately need a social norm in which the good of others figures more prominently in our personal goals”.

– Wolfgang Münchau, meanwhile, assesses the implications of an Irish “No” vote in the upcoming referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. “There is an intrinsic problem for the Yes campaign in Ireland”, he suggests, “which is that the core of the treaty was negotiated seven years ago. This is a pre-crisis treaty for a post-crisis world… If we had to reinvent the treaty from scratch, we would probably produce a very different text”.

– Finally, last week saw the German Marshall Fund of the US publish its Transatlantic Trends survey for 2009. Unsurprisingly, a majority of Europeans (77%) support Barack Obama’s foreign policy compared to the 2008 finding for George W. Bush (19%); though the “Obama bounce” was less keenly felt in Central and Eastern Europe than Western Europe. A multitude of other interesting stats – on attitudes to Russia, Afghanistan, Iran, the economic crisis, and climate change – can be found here (pdf).

by Michael Harvey | Aug 4, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, UK

– In the week leading up to the first anniversary of the Russia-Georgia conflict, the FT reports on the lingering regional tensions still apparent, while openDemocracy assesses some of the war’s wider implications for the US, EU, China and Turkey. Georgia aside, James F. Collins, former US ambassador to Russia, highlights the current fragility of US-Russia relations and the importance of “sustained dialogue within a solid institutional framework” if measured progress is to continue.

– Elsewhere, in a taster of the forthcoming Quadrennial Defence Review (QDR), two senior Pentagon officials survey the global landscape and assess what this means for the US’s strategic outlook. The main challenge (alongside adapting to the realities of hybrid warfare and a growing number of failing states), Michele Flournoy and Shawn Brimley suggest, will likely revolve around competition for the global commons (sea, space, air and cyberspace). A successful approach, they argue, should see the US refocus its efforts on building strong global governance structures and taking the “lead in the creation of international norms”. Andrew Bast at WPR comments that this could once again herald a US foreign policy with Wilsonianism firmly at its core.

– Der Spiegel, meanwhile, takes an in-depth look at the growing global market for farmland. In what it labels the “new colonialism”, the article notes the implications of such investment flows for states in Africa and Asia, as well as gauging the impact on local farmers.

– Climatico assesses Nicolas Sarkozy’s climate change credentials, highlighting his “erratic behaviour” on the issue and suggesting that the French stance is one to watch in the run up to Copenhagen.

– Finally, an interesting PoliticsHome poll on attitudes of the British public to the country’s foreign policy. 65% of voters, it indicates, agree that foreign policy has weakened Britain’s “moral authority” abroad – a view held across the political spectrum. Perhaps more strikingly, however, a majority (54%) felt the country should scale down its overseas military commitments, even if this meant ceding global influence. Interestingly, 57% were in favour of humanitarian intervention. Writing in Newsweek, meanwhile, Stryker McGuire adds to the narrative of declinism. The current economic crisis, he argues, has finally put paid to Britain’s attempts to maintain its world role and place at the international top table.