by Alistair Burnett | Oct 8, 2010 | Conflict and security, Global system, UK

Three weeks, three party conferences, but what did they tell us about where the parties see Britain’s place in the world?

First up were the Liberal Democrats in Liverpool.Their first conference as a party of government and junior Foreign Office Minister, Jeremy Browne, who described himself as the longest serving Liberal in the Foreign Office since 1919, gave the foreign affairs speech.

He made the now obligatory reference to the rise of China, India, Brazil and other powers and said Britain and Europe can’t stop this, but instead should seek to make it a force for good.He also argued that Britain still has a lot to offer and should be a catalyst for this new world order. It was short on specifics or examples of how this could be done, and how different is this from David Miliband’s talk when he was Foreign Secretary, that Britain should be a ‘global hub’?

The Lib Dems’ junior Defence Minister, Nick Harvey, focussed on one of the party’s keynote policies – a review of the need for a like-for-like replacement of Trident. In his speech, Nick Harvey argued for delaying the decision until after the next election, but his reasons appeared less about giving more time to consideration of the options and more about wrong footing the Labour Party. An argument that could give the impression that debate on a fundamental issue like the future of Britain’s nuclear weapons capability is being used as a tool to embarrass political opponents.

Next to Manchester and Labour’s conference. Being the first since losing power, it, perhaps understandably, witnessed quite a bit of raking over the recent past – both from internal critics of the last government and from former ministers defending their records.

A fringe meeting on the future of defence policy I went to heard concerns from trade unions and defence contractors about the potential impact on jobs and the industrial base of the defence cuts expected from the ongoing Strategic Defence and Security Review. The former Defence Secretary, Bob Ainsworth, was on the panel and on the defensive, responding to questions about his record with jibes back at some of his questioners.

The thing lacking was much discussion of what kind of role Britain should play in the world and what kind of military forces will be required for that. The defeat of David Miliband for the leadership and his decision to return to the backbenches inevitably meant there was less focus on his foreign policy speech to the conference than on discussion of his legacy, including as Foreign Secretary. On The World Tonight, journalist Ann McElvoy argued his main legacy was that in the wake of the Iraq war, which many believe was a big mistake, he made the case for Britain to retain its global reach and the need for intervention when the time is right, especially in Afghanistan.

On to the Conservatives in Birmingham.In the wake of the leak to the Daily Telegraph of Defence Secretary Liam Fox’s letter to David Cameron arguing against deep cuts to his budget, the mood among the Tories’ defence team seemed more upbeat, suggesting their rearguard action ahead of the Comprehensive Spending Review may be having some success. And, almost inevitably, discussion over Britain’s role in the world at the conference was dominated by the defence review as it nears completion.

The defence fringe I went to was a bit more wide-ranging than its Labour equivalent. The Defence Minister, Peter Luff, said the government is looking to France to be a strategic partner along with the US. He also suggested Britain would seek to work with France to develop new weapons systems bi-laterally, rather than enter new multilateral projects like the Eurofighter ‘Typhoon’. But the argument over what role Britain should play in the world came mainly from Nick Witney of the European Council on Foreign Relations rather than the politicians on the panel.

All this left me thinking that if the party conferences reflect the way the main parties are looking at Britain’s future global role, it does seem their focus is still very much on the defence review and cuts, rather than the more fundamental question of what role the UK should play in the changing world order. If there is a wider debate going on about what the UK’s military forces should be for, rather than simply what can be afforded, it seems to be going on largely behind the scenes. Whether that is wise is another matter.

by David Steven | May 6, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

I thought I could safely ignore the election for a few hours this evening. I voted days ago by post. And not much normally happens before the polls close at 10 pm.

But the past few hours has seen worrying economic tremors – as a raft of bad news from China and Europe, combined with skittishness over what will happen in Westminster tomorrow, drove a panic in the markets (with a trader’s error possibly fuelling the chaos [for more – see Felix Salmon]).

A 4 per cent drop in Chinese stocks started the downbeat mood, which carried over to Wall Street’s S&P 500 index, which was down 6 per cent to 1,065 – its sharpest correction in over a year, erasing its 2010 gains in one afternoon. The VIX index of market volatility spiked to its highest in a year.

“It’s really shocking,” said Jeff Palma, global strategist at UBS. “Stocks fell to minus nine on the year within seconds, that was a pretty shocking move. This is not your normal every day pull back, this is a pretty full-on collapse in risk appetite.”

As Alex pointed out earlier this week, bond markets will be open at 1 a.m. (in just four hours’ time) – at which they throw fuel onto the fire if they so choose:

Bond traders will be able to react in real time to results rolling in from key marginal seats, in other words: so as well as measuring how the night’s going through the traditional BBC swingometer, we’ll also be able to track progress through yields on three month short Sterling interest rate futures. Well, great.

All this reinforces how the UK – bereft of leadership throughout the campaign – has been sleep walking as a new economic reality (and a pretty disastrous one, at that) unfolds around it.

That’s why, over a week ago now, I called for the Chancellor (for now, at least) Alistair Darling to get off the campaign trail and get back behind his desk:

Election or no election, the UK simply cannot afford to sit on the sidelines while this crisis runs out of the control. Alistair Darling needs to stop giving speeches to activists in Scotland and get back to work at the Treasury.

Lord Adonis stopped campaigning as soon as Eyjafjallajökull erupted. Darling must do the same as the UK faces contagion from Eurozone turmoil.

Let’s hope he is at work now. Until a new PM has the ‘confidence of the House’ (and if results are close, that could take days to work out), he is 100% responsible for the British economy.

If necessary, he needs to haul in George Osborne and Vince Cable, and hammer out a consensus behind any short-term fire-fighting measures that might be necessary.

Once we have a new government – and assuming we have weathered any immediate post-election crisis – the team (of whatever political colour) will need to take an extremely active approach to economic policymaking.

Gordon Brown may have got the UK into this mess (he did), but there can be little doubt that the British government has played an important, and at times pivotal role, in trying to patch things back together again.

You just have to look at the absolute mess that the Germans and French have made of responding to the Greek crisis to see that this is a time when any half-way competent hand needs to be called onto the bridge.

I continue to believe that we’re seeing the latest stages of a crisis that stretches back until at least the late 1990s. This long financial crisis should force leaders to admit that they are part of an economic system that (i) they don’t understand; and (ii) seems to becoming more volatile, rather than less.

So how should the new PM and his Chancellor react? Here are three pointers – each of which cover the UK’s international economic policy (and its domestic policy, insofar as it is important to broader global financial stability).

First, the new government needs to balance the risks inherent in high levels of public and private debt.

We have heard a lot about the government’s deficit in this election, and quite a bit about its overall debt. But almost nothing has been said about colossal levels of private debt.

Private citizens owe much more than the government – most of it in the form of mortgages, secured against a residential property market that is significantly overvalued. (I wrote at length about the election and the housing crisis here.)

It’s no good trying to appease the global financial markets simply by cutting spending or raising taxes. Stall the recovery and unemployment will shoot up, while property prices will head down, threatening the banks again, and sending the tax take much lower.

No-one is going to be fooled into believing that the government can repay its debt, if we are hit by the twin nightmares of a double dip recession and housing market crash. That really would be game over.

So what can the government do?

There is so little room for manoeuvre that the unfortunate answer may be: nothing. However, I think the best strategy would be as follows:

- Take immediate and dramatic action to cut the structural deficit (I’d raise retirement age immediately, and then peg it to life expectancy – but any package of credible long-term tax or spend commitments would do).

- Avoid raising taxes or cutting spending by much in the short term, as the economy is still too fragile to take it (the government should probably make less of a song and dance about its caution here).

- Be explicit with the markets that interest rates will be kept low (propping up the housing market and boosting growth), even as the economy recovers – that the government’s main weapon against inflation will be its own spending. Think of this as a piece of reverse-Keynesianism.

- Take action to ensure that today’s secondary bubble in the housing market is not allowed to inflate further. Plans to cut stamp duty, for example, should definitely be put on hold. We don’t want housing prices to fall too fast, but neither should they be allowed to rise above today’s totally unsustainable levels.

Second, the government needs to get stuck into the Eurozone crisis, as I recommended in my post on Europe earlier this week, when I recommended that it should be:

…aiming for (in order of preference): (i) A strengthening of the Euro with greater sharing of economic sovereignty among Eurozone members (but with the UK left on one side); or (ii) An orderly removal of the weaker economies from the single currency.

Even on the Euro, the UK has some influence as an honest broker, given its position as an interested party, but not a full player. Cameron should adopt this role wholeheartedly – reminding British voters that the disorderly breakup of the single currency would be absolute disaster for the UK economy.

Third, we need to get the G20 back on track.

It briefly emerged as the forum for tackling the global economic crisis, but has now gone AWOL for, I suspect, a number of reasons:

- Obama is embroiled in a political system that cannot make foreign policy decisions.

- The Chinese are still bruised after Copenhagen.

- The Eurozone powers have utterly lost their nerve, and

- The Brits have left the field as the election approached.

Only the G20 has any hope of steering the global economy through what seem certain to be some exceptionally rocky times. If it is allowed to become a hopeless talking shop like the G8, then I think we are probably screwed.

Over the next year or so, the UK’s G20 policy will be its foreign policy. It’s essential that we have some radical new ideas to put on the table.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | Apr 29, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

If the BBC leaders’ debate tonight devotes more time to bigotgate than to housing, I am going to dedicate the rest of my days to working for the Corporation’s demise.

Britain’s unsustainable housing market is at the root of many of the country’s problems and could wreak appalling damage on voters during the next parliament. It must feature in the debate.

Someone should start by reminding Gordon Brown of a promise he made in his first budget speech in 1997:

Stability will be central to our policy to help homeowners. And we must be prepared to take the action necessary to secure it. I will not allow house prices to get out of control and put at risk the sustainability of the recovery.

As I argued recently:

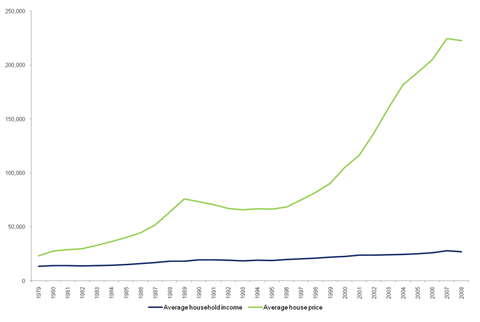

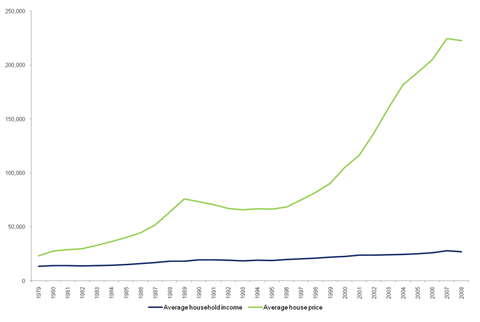

When Brown spoke, the average house cost £75k – about £10k above the early 1990s nadir. A long long boom was just beginning. Prices would peak in February 2008 at an average of… £232k!!!

In other words, Brown promised not to let house prices spiral out of control and then allowed them to treble, during a period when household disposable income increased by only 30% or so.

2007 saw what is often called a housing price crash, but as this graph shows, it was really only a blip.

As the government pumped money into the economy and pushed interest rates to unprecedented low levels, the bubble started to inflate again. House prices are now back to the levels of June 2007.

Second guessing the housing market is a mug’s game, surely this is unsustainable. British houses are overvalued by nearly a third, according to one measure. Worse is the amount of mortgage debt outstanding – $1.238 trillion. By comparison, government debt is ‘only’ £950 billion.

Low interest rates and buoyant employment (relative to the economy’s woeful performance) have kept householder’s head above water – but the highly-indebted remain highly vulnerable to any increase in interest rates or to further job losses.

My best case for the housing market is a long period of stagnation (we desperately need lower prices). Worst case would be a sudden, vicious and self-fulfilling collapse. I believe this is currently the most serious economic risk facing the British people (one which is, of course, interrelated to Europe’s sovereign debt problems).

So what do the major parties have to say about this in their manifestos?

- Labour wants to expand home ownership and exempt all houses under £250k from stamp duty (likely to push house prices up). It says it will build 110k houses over two years (likely to push prices down).

- The Conservatives promise to exempt first time buyers from stamp duty if their house costs less than £250k. It wants to put communities in charge of planning, which is highly likely to reduce the number of houses built.

- The Lib Dems plan to use loans and grants to bring 250k empty houses back into use.

Pretty weak beer, all told. No party questions the shibboleth that Britain needs more homeowners. None is prepared to explain how they will manage risks that have been increased by the response to the financial crisis.

Far less do they have policies to fulfil Brown’s promise from 1997 – to end boom and bust in the housing market radical proposals (see my Long Finance paper) to prevent the mortgage market from screwing borrowers every twenty years or so.

So here’s my question for tonight’s debate:

In 1997, Gordon Brown promised he’d never let house prices get out of control again, but then presided over a housing bubble that has left British householders owing £1.2 trillion on their mortgages. In government, what will you do to stop the housing dream from becoming a housing nightmare?

by David Steven | Mar 12, 2010 | UK

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CP9_kkzfN-w[/youtube]

It’s no wonder the markets are raising questions about UK public finances – neither of the main parties has anything approaching a clear message on fiscal tightening.

From Labour, you get blithe assurances on taxes. Liam Byrne didn’t quite ask us to read his lips yesterday when promising no new tax increases, but he might as well have done. Carl Emmerson from the Institute for Fiscal Studies was unimpressed:

I cannot see how the Government can promise to not affect front line services when you look at the scale of the cuts they have got to plan for.

Liam Byrne is talking just about the first four years and after that there will undoubtedly have to be more pain and that is likely to be tax rises or even greater public sector cuts.

But the Tories are not in the clear either. I was baffled by William Hague’s recent speech at the Conservative Party Spring Forum. Half way through his speech, he lays out the Tory pitch to the undecided voter:

And to those who say they do not know what the Conservatives will do, let us tell them. We will cut the spending that cannot go on and the borrowing that leads to ruin.

So what follows? Here are all the commitments Hague makes that will cost money:

(i) Cutting taxes on business to give the UK the ‘most competitive’ tax environment in the G20

(ii) reversal of Labour’s planned national insurance increase

(iii) abolition or reduction of inheritance tax

(iv) two year freeze on Council tax (despite promises of the ‘biggest ever’ transfer of power to Councils)

(v) stamp duty abolished for first time buyers (despite unsustainable prices in the housing market)

(vi) more university places and apprenticeships

(vii) nursing care in their homes for the elderly.

And here are all the commitments is the only commitment that will clearly save money (though not much):

(i) Scrap ‘a large slice’ of expensive quangos.

And voters are supposed to be convinced this adds up to “vision of a Britain restored.”

Both parties need to convince the electorate they can get Britain back on its feet (the slogan I’d advise either to run their campaign under). But as Martin Wolf argues in today’s FT, at the moment it’s shaping up to be an election that both sides deserve to lose.