by Ryan Gawn | Jul 22, 2015 | Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Global system, Influence and networks, UK

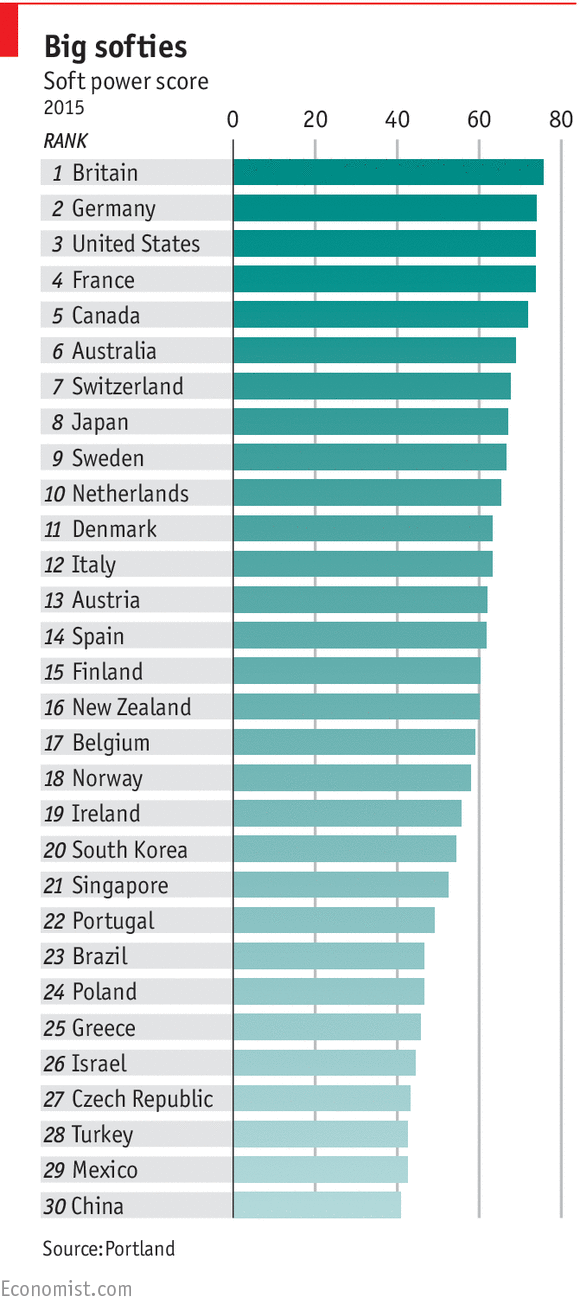

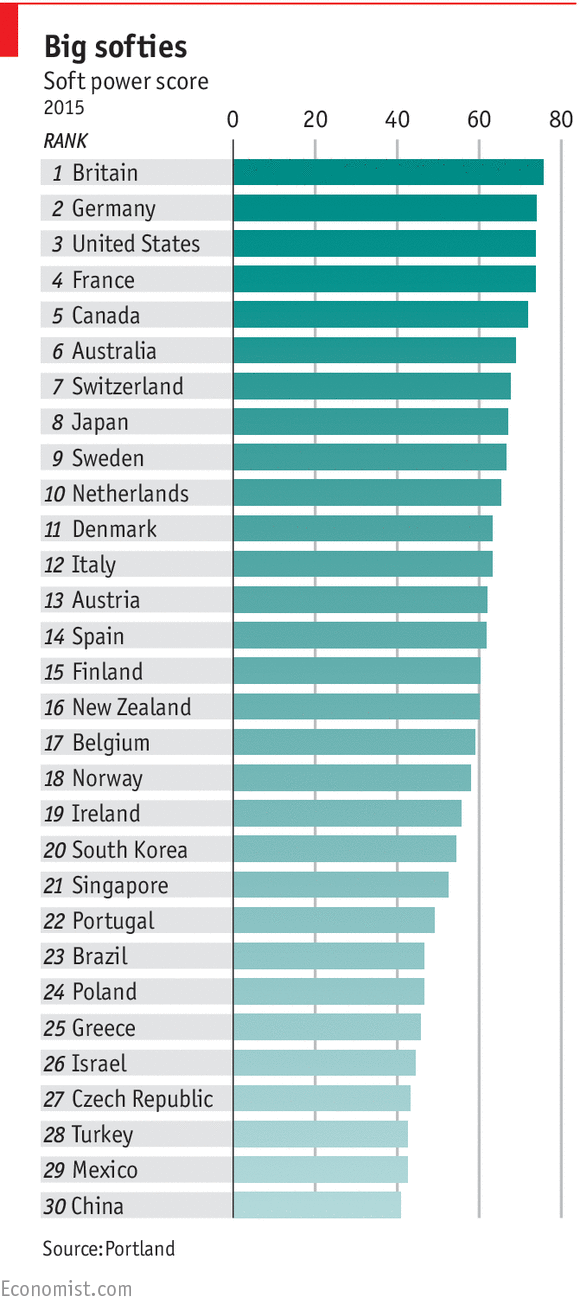

Last week saw the launch of a new global #softpower report, ranking the UK at the top of a 30-country index. Compiled by Portland, Facebook and ComRes, the report is described by Joseph Nye (who coined the term in 1990) as “the clearest picture to date of global soft power”, and has ranked countries in six categories (enterprise, culture, digital, government, engagement, education).

There are quite a few of these indices around now, with varying methodologies – nevertheless, this is the first to incorporate data on government’s online impact and international polling. Who’s at the top of the tables isn’t really surprising (the top 5 countries – UK, Germany, US, France, Canada – are identical to the top 5 in the Anholt-GFK Roper Nation Brand Index, but with a slight reordering of ranking). The US, Switzerland and France topped the specific categories, and although not first place in any of the categories, the UK ranked highest overall, reflecting its strength in culture, education, engagement & digital. More on the UK later.

What is really surprising is that China finishes last. Following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets (such as the Xinhua news agency, aid/ development projects), at a time when others have been paring back their ambitions. Nevertheless, the impact of this investment isn’t borne out in the results, likely hindered by negative perceptions of China’s foreign policy, questionable domestic policies and a weakness in digital diplomacy. China came out strongest in the culture, likely reflective of the many Confucius Institutes dotted around the globe.

There are a few other interesting nuggets:

· Broader power trends are increasing the need for soft power – 3 factors driving global affairs away from bilateral diplomacy and hierarchies and toward a much more complex world of networks:

1. Rapid diffusion of power between states

2. Erosion of traditional power structures

3. Mass urbanisation

(more…)

by Alistair Burnett | May 25, 2013 | Global Dashboard

China and India are the two giants of what are called the emerging powers – they are the ’I’ and ‘C’ in the BRICS – but despite their membership of that grouping, relations between them have long been uneasy.

They fought a brief war in 1962 high in the Himalayas over their disputed border. It ended with India humiliated and to this day anti-Chinese rhetoric is commonly heard at demonstrations and in the Indian media. For their part, the Chinese resent that India has hosted the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, and the Tibetan government in exile, since they fled after the failed Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule in 1959.

I wrote last week that China’s maritime borders remain tense and a possible flashpoint. But this week, there is potentially better news from China’s south western border where Beijing has taken a significant step to improving relations with India with a visit to Delhi by the new Chinese Prime Minister, Li Keqiang.

The visit followed a month when tensions had been running high after soldiers from the two sides moved into an area on the disputed border and faced off. This ended when ahead of Mr Li’s scheduled visit, senior officials from both sides picked up the phone and agreed to pull their troops back.

There had been pressure on the Indian government not to back down with anti-Chinese protests in several parts of the country and expressions of outrage in mainstream and social media. In China, there was little public and media reaction as the incident went largely unreported, although past studies of how India is viewed on Chinese social media suggest a none too flattering opinion – more condescending than hostile.

So why did both governments decide compromise was better than confrontation?

You won’t be surprised to hear that part of the answer is economics. As both countries have grown rapidly over the past decade, trade between them has shot up from $2 billion to $75 billion a year and China is now India’s largest trading partner. Although, there are concerns in Delhi about the size of the trade deficit, both sides are keen to see this grow further and during this week’s talks Li Keqiang told his counterpart, Manmohan Singh, that Beijing would address the trade deficit.

China has clearly decided that better relations with India are a priority. The official media made much of the fact this was Mr Li’s first official trip abroad since taking office in March and has talked up the visit. On arriving in Delhi, Li said the fact it was his first foreign trip showed “the great importance Beijing attaches to its relations with Delhi”.

What he didn’t explicitly say was why. And, in addition to trade, the answer there seems to be the United States.

Washington has made a huge effort to improve its relations with India over the past few years, even going as far as to sign an agreement on civil nuclear cooperation in 2008 despite the fact India never signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty and has developed its own nuclear weapons arsenal.

Many in Beijing have interpreted this as part of an American attempt to contain China. The Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia”, which has seen the US boost its military and diplomatic focus on China’s neighbourhood, has intensified Beijing’s concerns. Some China-watchers have dubbed this the “go west” strategy – facing containment on its eastern seaboard where it is ringed with allies and friends of the US like Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines, Beijing has decided to give itself options to its west.

This may lead to better relations between China and India which makes for a more stable world, but not everyone gets to benefit.

This week, my programme, The World Tonight, heard from some of the people who are losing out in a rare report from Nepal. Traditionally, India has had the greatest influence over Kathmandu, but in recent years China has become more influential. Many Tibetans fleeing Chinese rule of their homeland end up in neighbouring Nepal, but the Nepalese government, allegedly out of deference to China, is restricting their entry and making life difficult for those who get across the border.

A reminder of the human cost of great power politics which remains as much a factor of today’s world as it has throughout history.

by David Steven | Jan 10, 2011 | Climate and resource scarcity, South Asia

On the face of it Pakistan may have bigger things to worry about, but recent weeks have seen it fall out with India over the humble onion:

The pungent vegetable is now at the centre of a mini diplomatic storm that has further soured relations between both countries over the past few days. The Pakistani commerce ministry banned the export of onions across the border by road and rail due to high prices and shortages at home.

Food inflation is running high across South Asia and onion prices are soaring in both Pakistan and India, as the two have had bad harvests of the crop. Reported hoarding and speculation in India have added to the crisis.

Onions are a touchy subject in India and past price hikes have brought down governments. In retaliation, farmers in Indian Punjab have stopped exporting vegetables to Pakistan.

A sideshow, surely, to the really big issues like Kashmir or religious extremism? Maybe not. You can’t spend anytime in Pakistan without noticing the powerful role played by resource scarcity in the country’s politics.

It all goes back to the global food and energy price spike of 2008. According to the IMF, growth had been robust up until that point and government finances were in reasonably good shape.

Conditions deteriorated in mid-2008 with the sharp increase in international food and fuel prices and worsening of the domestic security situation. The fiscal deficit widened, due in large part to rising energy subsidies, financed by credit from the central bank.

As a result, the rupee depreciated and foreign currency reserves fell sharply. Inflation reached 25 percent in mid-2008 [mostly food], causing harm to vulnerable social groups.

The country has never really made it back onto an even keel. The global economic crisis gave Pakistan a little relief, pushing commodity prices sharply lower, but the public finances never recovered.

And as food and energy prices have risen again, Pakistan has been hit by a succession of mini-commodity shocks (the sugar crisis of 2009 and 2010, the flour crisis of 2010). Some estimates suggest that higher food prices have led to a precipitous decline in caloric intake (though robust data is hard to track down).

Gas and electricity are in critically short supply, leading to frequent load shedding, for consumers, business, and industry in winter. Around the major cities, one sees trees being stripped bare by people desperate for heat for their houses and businesses:

Shopkeepers operating in the streets and mohallahs are using pieces of wooden and cardboard crates and other packing material to brace the chill in the air.

Many Lahorites are having ‘bonfires’ even during day time. An empty tin of cooking oil is usually converted into a hearth by making holes in it. Old newspapers, textbooks and copies besides parts of broken furniture are used to make fire as it is hard for many to afford Rs1,200 per 40 kilo fire wood or Rs40-50 per kilo coal.

There are no easy solutions. Pakistan has also been under intense pressure from the IMF and the United States to reduce fuel subsidies, in order to cut its deficit and meet the conditions of its IMF loan.

But its attempts to comply simply fuelled political instability. The PPP-led government came close to falling when it attempted to push up the cost of petrol at the end of 2010. Backing down was the price of getting its junior partner, MQM, back into the coalition late last week.

The result, though, has been unwelcome speculation that Pakistan may on the road to default – a worry that is likely to intensify as oil prices head ever higher.

Inflation is now up to 16%, with food prices expected to rise 20% in December 2010 (year-on-year). In November last year, onions jumped in price by 67% in just one month alone.

As in 2008, many of the drivers of the crisis are regional and global. While the attention of the world is fixated on Pakistan’s struggle with religious extremism. In the background, the struggle for resources seems to be doing as much to push this country towards ruin.

by Alistair Burnett | Aug 5, 2010 | Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia

Two years ago, Georgian forces shelled the capital of the breakaway region of South Ossetia hitting the base of Russian peacekeepers as well as civilian housing. Russia responded immediately with a massive ground and air assault and in five days inflicted a heavy defeat on its tiny neighbour, occupying a band of Georgian territory into the bargain.

The conflict had several immediate results.

Already fraught relations between Moscow and Tbilisi plunged to new depths and diplomatic relations were severed.

Russia and three other countries recognised the independence of the breakaway Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

And relations between Russia and the West – the US and the EU – deteriorated to their worst level since the collapse of the USSR – there was even talk of a new Cold War from western politicians.

The Cold War analogies led some commentators to argue Russian foreign policy had taken a decisive anti-western turn and things could and/or should never be the same again

Two years later, the one thing that seems unlikely to ever be the same again is the shape and size of Georgia. If recognition from Russia was not enough, the recent International Court of Justice opinion that Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence was not against international law, makes it even less probable Tibilsi could regain control of its lost regions. (more…)

by Michael Harvey | Jul 30, 2010 | Climate and resource scarcity, Cooperation and coherence, East Asia and Pacific, Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, South Asia, UK

– Over at The Diplomat, Thomas Wright explores how China’s self-confidence in initial relations with the Obama administration may prove the “catalyst for a more competitive – and geopolitically savvy – US multilateralism.” Der Spiegel, meanwhile, highlights the extent of Chinese soft power, while Charles Grant sees a chance to enhance the EU’s relations with the emerging superpower.

– Focusing on Chinese domestic society, the Economist highlights the growing activism and changing dynamics of the country’s vast labour force, with its associated implications for the global economy. Analysis over at VoxEU, meanwhile, assesses evidence of a potential Chinese property bubble.

– Elsewhere, with David Cameron back from his visit to India, Adrian Hamilton and Geoffrey Wheatcroft offer their views on his approach to international affairs. Kim Sengupta meanwhile remarks that the new Prime Minister “has started his foreign policy journey with a series of very deliberate steps”.

– Finally, Sir John Sulston talks to the New Scientist about the implications of global population change for sustainable development – the subject of a new initiative that he’s leading for The Royal Society. Prospect Magazine‘s blog, meanwhile, highlights favourable demographic trends in the developing world, while figures this week confirm that the EU’s population has now passed the 500 million mark.