by Seth Kaplan | Jan 16, 2013 | Africa, Conflict and security, Economics and development

Samuel Huntington argued in his 1968 classic Political Order in Changing Societies that rapid development could be highly destabilizing:

Social and economic change—urbanization, increase in literacy and education, industrialization, mass media expansion—extend political consciousness, multiply political demands, broaden political participation. These changes undermine traditional sources of political authority and traditional political institutions; they enormously complicate the problems of creating new bases of political association and new political institutions combining legitimacy and effectiveness. The rates of social mobilization and the expansion of political organization are high; the rates of political organization and institutionalization are low. The result is political instability and disorder. The primary problem of politics is the lag in the development of political institutions behind social and economic change.

Richard Joseph, a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution and a Professor at Northwestern University, discusses a similar point in a recent article on Africa. In it, he introduces the very useful phrase “discordant development,” defining it as:

More than just “unequal development,” but rather how deepening inequalities and rapid progress juxtaposed with group distress can generate uncertainty and violent conflict.

This is a common problem in fragile states. One area moves forward while another area does not — or worse. And because countries are weakly unified, such development is highly discordant, increasing instability by how it increases the exclusion — and feelings of exclusion — of certain groups. (more…)

by Seth Kaplan | May 1, 2012 | Africa, Conflict and security

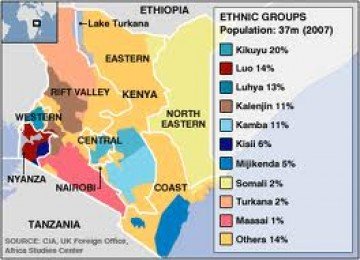

What type of ethnic divisions and political circumstances are most likely to produce conflict?

There is no easy answer, but there are formulas that can provide a guide. (more…)

by Seth Kaplan | Apr 10, 2012 | Conflict and security, Economics and development

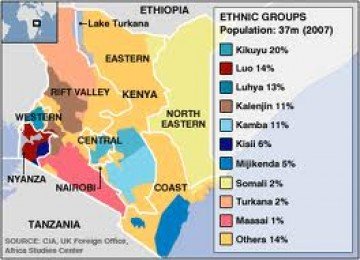

A new book edited by Jeffrey Herbst, Terence McNamee, and Greg Mills discusses the most important problem in fragile states: weak social cohesion. It looks at “fragmented and weak states, made up of many nations and cutting across geographical, racial and religious boundaries” and explores why some countries with potential “fault lines” produce conflict while others are better at managing them.

A new book edited by Jeffrey Herbst, Terence McNamee, and Greg Mills discusses the most important problem in fragile states: weak social cohesion. It looks at “fragmented and weak states, made up of many nations and cutting across geographical, racial and religious boundaries” and explores why some countries with potential “fault lines” produce conflict while others are better at managing them.

More than a dozen authors contribute case studies on a broad range of countries including South Africa, Northern Ireland, Iraq, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, India and even Canada and seek solutions that can be transferred elsewhere.

Over and over again, they learn that “the nature of the fault lines was far more complicated than the simple headline assigned to a country.” In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for instance, Pierre Englebert finds an extraordinarily complicated picture, with “multiple and overlapping local fissures, widely distributed across the country, which contribute to a fragmentation of identities and networks at the local level and increased polarization of social life.” Christopher Clapham writes that Ethiopia is “riven by conflicts along almost every fault line–ethnic, religious, ecological, class, ideological, political–many of which are broadly aligned . . . Conflicts within Ethiopia itself spread across state frontiers–especially those with its three most important neighbors.” (more…)