by David Steven | Apr 21, 2010 | Cooperation and coherence, UK

So the UK’s airspace is open again after the Civil Aviation Authority issued this rather plaintive statement:

The CAA has drawn together many of the world’s top aviation engineers and experts to find a way to tackle this immense challenge, unknown in the UK and Europe in living memory.

Current international procedures recommend avoiding volcano ash at all times. In this case owing to the magnitude of the ash cloud, its position over Europe and the static weather conditions most of the EU airspace had to close and aircraft could not be physically routed around the problem area as there was no space to do so.

We had to ensure, in a situation without precedent, that decisions made were based on a thorough gathering of data and analysis by experts. This evidence based approach helped to validate a new standard that is now being adopted across Europe.

The major barrier to resuming flight has been understanding tolerance levels of aircraft to ash. Manufacturers have now agreed increased tolerance levels in low ash density areas.

The no-fly zones – if they are the same agreed by Eurocontrol – are a few tiny patches of sky, leaving the media increasingly convinced that the past week has been a to-do about nothing (cf. BSE, swine flu).

With the crisis seemingly ending in farce, let’s hope there’s not a final tragic act (a plane loses an engine or falls out of the sky) or sequel (Katla erupts). If that happens, journalists will swiftly execute a U-turn – to complain that governments have been reckless in putting passengers’ lives at risk, or have failed to equip the world’s aircraft with the sensors that can keep them flying when ash is in the air.

It’s still not clear to me how a few test flights – which one expert yesterday derided as evidentially useless – have allowed a safe level of ash for jet engines. According to the Guardian, however, there has been a tussle over the issue that long pre-dates this crisis, with industry (afraid of legal action) previously arguing for a rigid application of the precautionary principle.

When the inevitable enquiry is announced, I hope it is given a broad remit to look at how European society responded to the crisis, and not just be charged with focusing on technical issues.

As I have argued on Saturday morning, governments allowed themselves to get behind the curve on the crisis and never recovered; the media was always uncomfortable with the issue (until it settled on someone to blame); while the public response (including widespread use of social media) tells us a lot about how we are and are not resilient in the face of crisis.

All these aspects should be studied by the enquiry team.

In the UK. a lot of attention will quite rightly focus on how three organisations worked together – the CAA, NATS (the air traffic controllers), and the Met Office. While it is hard to know what went on behind the scenes, in public, the relationship between the three seemed increasingly strained.

At the start of the crisis, NATS was very happy to be in the lead. Over time, it became increasingly keen to pass the buck, underlining that it was only following advice given it by its fellow members of the ‘no fly’ triad.

Communication from the three organisations was woeful, in marked contrast with the much more proactive approach of Eurocontrol. I fail to understand why Ministers did not force them to run regular joint press conferences – and to establish a shared web portal (backed up by a Twitter feed) to provide regular and comprehensive updates.

Here’s a thread I think the enquiry might like to pick at, taking it into the opacity and vagueness of official communications. What on earth happened to the mysterious ‘second cloud’ that NAS was warning us about only the night before last?

Since our last statement at 1530 today, the volcano eruption in Iceland has strengthened and a new ash cloud is spreading south and east towards the UK. This demonstrates the dynamic and rapidly changing conditions in which we are working. Latest information from the Met Office shows that the situation is worsening in some areas.

I never saw any other evidence that this new cloud really existed (though perhaps it did) – but its existence was unquestioningly reported by media on both sides of the Atlantic. How, if the situation was worsening, could airspace be reopened just 24 hours later?

For all Global Dashboard coverage of the crisis – click here. Plus some risk management lessons from the Economist. Also, John Kay. And Sue Cameron gives Lord West a pasting for deploying the navy.

by David Steven | Apr 19, 2010 | Cooperation and coherence, UK

My take (1, 2, 3) on complex emergencies such as the Eyjafjallajökull crisis is that governments have to get ahead of the curve, or be steadily choked by competing pressures from scientists, industry, the media, and public.

So what’s coming up on the horizon? At some stage, UK airspace is going to reopen – and there’s going to be an almighty battle for scarce landing and take-off slots. What I want to know is:

- Is anyone working with the airlines to make sure that priority is given to helping Brits stranded abroad or non-Brits stuck in the UK?

- Are there plans to ensure that non-essential flights (e.g. internal flights, commuter planes to Brussels etc.) are the last to be given the chance to take off?

- Can anything be done (sharing flights between airlines, running bigger planes on key routes) to maximize the speed with which schedules return to normal?

I don’t know how long it is likely to take for things to get back to normal – but it’s worth remembering that there could be only brief windows when travel is possible. And that a fresh eruption could quickly make things worse again…

Update (20/4 09.15): Doesn’t sound as if there’s been much coordination as yet.

Frances Tuke, spokeswoman for Abta – The Travel Association… warned that as attempts are made to restore order to travel plans, some of the Britons currently abroad could find those on scheduled flights are allowed to fly before those who have been stuck at airports or hotels for days.

“I don’t have the detailed logistics of what is going to happen,” she added. “I know that some of our bigger members are planning to have conference calls to talk about logistics.”

Update II (20/4 10.15): Another issue to start planning for: travel companies that start to go to bust once they begin paying out refunds. Will the government be forced to step in? Or will it take the heat generated by consumers losing out? And how does the decision get taken during an election campaign?

by David Steven | Apr 18, 2010 | UK

Yesterday, I warned that governments were losing control of the Eyjafjallajökull crisis:

In the UK, it doesn’t help that there’s an election on. But Lord Adonis, the Secretary of State for Transport, is not running for office. It would be good to see greater signs that he – or someone else – is being much more decisive about taking charge.

Apparently, there are more than a million British citizens still stranded abroad and the MET Office has said there will be no flights on Monday 18 April (no confirmation from NATS on that as yet). Both the media and airlines are clearly getting restless. A new narrative is crystallizing: that the threat from the ash cloud has been substantially exaggerated.

Albeit belatedly, British ministers have finally shown they are now more fully engaged with events, with five lining up in Downing Street for a press conference. COBRA will meet tomorrow morning.

In my opinion, however, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office should be much more specific about what its consular staff are doing. I’m talking about concrete and detailed briefing for the media.

How is it using its consular surge capacity (the Rapid Deployment Team)? How many extra staff have been deployed? In which airports does it have staff dealing directly with passengers and airlines? How, practically, are these staff managing to assist people?

The generalities on the FCO website are not nearly enough… [Relatedly: KLM masters social media. Air France fails.]

Update [19/04 9.30 am]: A few other thoughts. The UK government social media response has – so far – been distinctively unimpressive, despite the fact that many government departments, the FCO included, have very good social media team. (Good this morning, though, to see the gov Twitter feeds finally starting to use the Twitter #ashtag and #ashcloud tags)

In contrast, Eurocontrol – which oversees European airspace – has emerged as a model of best practice. Whoever it behind its Twitter feed is doing a stellar job – detailed factual updates, numerous responses to people’s questions, and all in an identifiably human voice.

Also, the pressure is clearly building on governments to downgrade the threat, based on test flights. But, say, a plane had a 1/1000 risk of getting into trouble (e.g. hitting a slightly thicker patch of ash during its flight), then you could run a dozen or so tests and have a very slim chance of hitting trouble. So you open Heathrow, which has 1300 flights every day…

Once again, the complex risk calculations at the heart of this crisis are making Anthony Giddens’s 1999 Reith lecture look very prescient:

There is a new moral climate of politics, marked by a push-and-pull between accusations of scaremongering on the one hand, and of cover-ups on the other. If anyone – government official, scientific expert or researcher – takes a given risk seriously, he or she must proclaim it. It must be widely publicised because people must be persuaded that the risk is real – a fuss must be made about it. Yet if a fuss is indeed created and the risk turns out to be minimal, those involved will be accused of scaremongering.

Suppose, on the other hand, that the authorities initially decide that the risk is not very great, as the British government did in the case of contaminated beef. In this instance, the government first of all said: we’ve got the backing of scientists here; there isn’t a significant risk, we can continue eating beef without any worries. In such situations, if events turn out otherwise – as in fact they did – the authorities will be accused of a cover-up – as indeed they were.

Things are even more complex than these examples suggest. Paradoxically, scaremongering may be necessary to reduce risks we face – yet if it is successful, it appears as just that, scaremongering. The case of AIDS is an example. Governments and experts made great public play with the risks associated with unsafe sex, to get people to change their sexual behaviour. Partly as a consequence, in the developed countries, AIDS did not spread as much as was originally predicted. Then the response was: why were you scaring everyone like that? Yet as we know from its continuing global spread – they were – and are – entirely right to do so.

This sort of paradox becomes routine in contemporary society, but there is no easily available way of dealing with it. For as I mentioned earlier, in most situations of manufactured risk, even whether there are risks at all is likely to be disputed. We cannot know beforehand when we are actually scaremongering and when we are not.

When dealing with risk, governments are almost always going to emerge at least somewhat discredited. The question is how badly

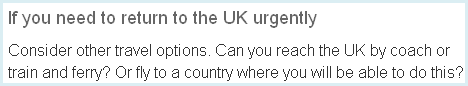

Update II [19/04 16.30]: The FCO website is still maddeningly unspecific. For example:

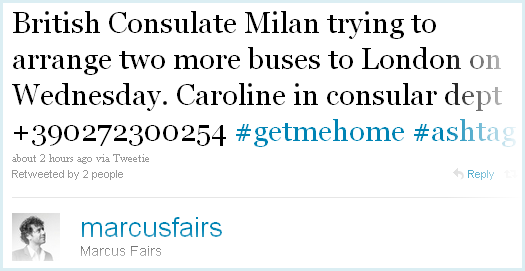

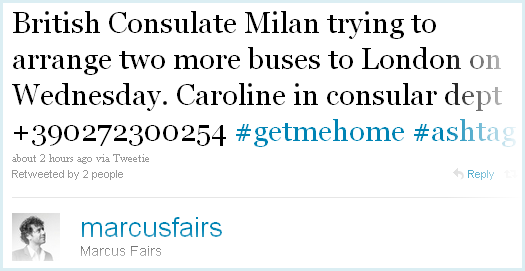

Meanwhile, here’s Marcus Fairs with some information that’s (i) much more specific and helpful; (ii) directly covers what named FCO consular staff are up to.

Also, it is increasingly clear that NATS – the UK’s air traffic control organisation – is floundering. No Twitter feed. A website that is still in emergency mode. And, worst of all, official updates on their site, but leaks to other news organisations with different information. Not good.

Update III [20/04 14.30]: Finally:

by David Steven | Apr 18, 2010 | Europe and Central Asia, Global system

Superb photo from NASA:

The MODIS instrument on NASA’s Aqua satellite captured an Ash plume from Eyjafjallajokull Volcano over the North Atlantic at 13:20 UTC (9:20 a.m. EDT) on April 17, 2010.

More coverage from Global Dashboard here and here. (h/t @TomRaftery). Plus: two great animations of the ash cloud dispersing over Europe (1, 2).

by David Steven | Apr 18, 2010 | Cooperation and coherence, UK

When crisis strikes, it doesn’t take long for people to start finding ways to help themselves.

On 9/11, a self-organising flotilla began to evacuate people from Manhattan even before the Twin Towers fell. Katrina saw the same improvised response.

The Coast Guard did not act alone in its sizeable rescue effort. An emergent and ephemeral flotilla of civilian boat operators also converged on the heavily damaged areas, both on their own initiative and in response to a call for assistance by political leaders. The ability of Coast Guard operational commanders to act relatively autonomously in the field, a strong-hold of experienced personnel, versatile training, an organizational environment that combines uniformed and civilian operations, and the development of a shared vision of what was necessary by both Coast Guard and civilian boat operators facilitated the ability to improvise at a multi-organizational level.

Interestingly, one of New York City’s most dramatic (albeit rarely mentioned) improvised response activities on September 11th, 2001 was the waterborne evacuation of Lower Manhattan… The harbor community did not have plans to execute a mass evacuation of the City, but vessels converged—again, some on their own initiative and others in response to the Coast Guard’s call for all available boats—to improvise a successful evacuation of hundreds of thousands of people. In fact, ferries, tugs, dinner cruise boats, and other private vessels played an even more significant role in the operation than actual Coast Guard vessels. This same operation quickly became involved in transporting critical equipment, supplies, and personnel to Manhattan on return trips to collect more evacuees

Today saw an attempt by Dan Snow to organize a Dunkirk-style evacuation from France, for those unable to get a plane home after Eyjafjallajökull shut down European airspace (more on Europe’s slow motion crisis, here).

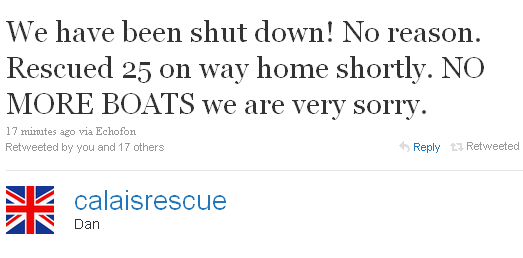

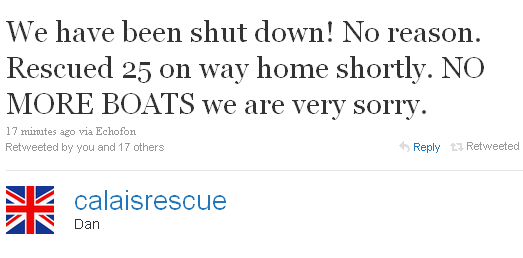

Dan has been tweeting as calaisrescue. Unfortunately, it seems the authorities have not taken too kindly to his efforts, bringing the rescue effort to a halt after just three boat loads got away:

It’s not yet clear exactly what happened (I am guessing a health and safety issue) – but any attempt to stamp on bottom-up resilience seems extremely short-sighted. After all, the 2003 European heat wave was such a disaster precisely because people didn’t help their neighbours.

The decision to stamp on the rescue could also make an interesting campaign theme for David Cameron, who has put the Big Society (and resilience, too) at the heart of his bid for office, providing a good example of where the state (presumably the French one, in this case) crowds out community-led initiative.

[BTW those interested in community resilience should read Charlie Edwards’s Resilient Nation – as well as these talks (1, 2) for RUSI.]

Update: BBC says ‘French officials’ took the decision… though there appear to be efforts ongoing to get the show back on the road.