by David Steven | May 6, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

I thought I could safely ignore the election for a few hours this evening. I voted days ago by post. And not much normally happens before the polls close at 10 pm.

But the past few hours has seen worrying economic tremors – as a raft of bad news from China and Europe, combined with skittishness over what will happen in Westminster tomorrow, drove a panic in the markets (with a trader’s error possibly fuelling the chaos [for more – see Felix Salmon]).

A 4 per cent drop in Chinese stocks started the downbeat mood, which carried over to Wall Street’s S&P 500 index, which was down 6 per cent to 1,065 – its sharpest correction in over a year, erasing its 2010 gains in one afternoon. The VIX index of market volatility spiked to its highest in a year.

“It’s really shocking,” said Jeff Palma, global strategist at UBS. “Stocks fell to minus nine on the year within seconds, that was a pretty shocking move. This is not your normal every day pull back, this is a pretty full-on collapse in risk appetite.”

As Alex pointed out earlier this week, bond markets will be open at 1 a.m. (in just four hours’ time) – at which they throw fuel onto the fire if they so choose:

Bond traders will be able to react in real time to results rolling in from key marginal seats, in other words: so as well as measuring how the night’s going through the traditional BBC swingometer, we’ll also be able to track progress through yields on three month short Sterling interest rate futures. Well, great.

All this reinforces how the UK – bereft of leadership throughout the campaign – has been sleep walking as a new economic reality (and a pretty disastrous one, at that) unfolds around it.

That’s why, over a week ago now, I called for the Chancellor (for now, at least) Alistair Darling to get off the campaign trail and get back behind his desk:

Election or no election, the UK simply cannot afford to sit on the sidelines while this crisis runs out of the control. Alistair Darling needs to stop giving speeches to activists in Scotland and get back to work at the Treasury.

Lord Adonis stopped campaigning as soon as Eyjafjallajökull erupted. Darling must do the same as the UK faces contagion from Eurozone turmoil.

Let’s hope he is at work now. Until a new PM has the ‘confidence of the House’ (and if results are close, that could take days to work out), he is 100% responsible for the British economy.

If necessary, he needs to haul in George Osborne and Vince Cable, and hammer out a consensus behind any short-term fire-fighting measures that might be necessary.

Once we have a new government – and assuming we have weathered any immediate post-election crisis – the team (of whatever political colour) will need to take an extremely active approach to economic policymaking.

Gordon Brown may have got the UK into this mess (he did), but there can be little doubt that the British government has played an important, and at times pivotal role, in trying to patch things back together again.

You just have to look at the absolute mess that the Germans and French have made of responding to the Greek crisis to see that this is a time when any half-way competent hand needs to be called onto the bridge.

I continue to believe that we’re seeing the latest stages of a crisis that stretches back until at least the late 1990s. This long financial crisis should force leaders to admit that they are part of an economic system that (i) they don’t understand; and (ii) seems to becoming more volatile, rather than less.

So how should the new PM and his Chancellor react? Here are three pointers – each of which cover the UK’s international economic policy (and its domestic policy, insofar as it is important to broader global financial stability).

First, the new government needs to balance the risks inherent in high levels of public and private debt.

We have heard a lot about the government’s deficit in this election, and quite a bit about its overall debt. But almost nothing has been said about colossal levels of private debt.

Private citizens owe much more than the government – most of it in the form of mortgages, secured against a residential property market that is significantly overvalued. (I wrote at length about the election and the housing crisis here.)

It’s no good trying to appease the global financial markets simply by cutting spending or raising taxes. Stall the recovery and unemployment will shoot up, while property prices will head down, threatening the banks again, and sending the tax take much lower.

No-one is going to be fooled into believing that the government can repay its debt, if we are hit by the twin nightmares of a double dip recession and housing market crash. That really would be game over.

So what can the government do?

There is so little room for manoeuvre that the unfortunate answer may be: nothing. However, I think the best strategy would be as follows:

- Take immediate and dramatic action to cut the structural deficit (I’d raise retirement age immediately, and then peg it to life expectancy – but any package of credible long-term tax or spend commitments would do).

- Avoid raising taxes or cutting spending by much in the short term, as the economy is still too fragile to take it (the government should probably make less of a song and dance about its caution here).

- Be explicit with the markets that interest rates will be kept low (propping up the housing market and boosting growth), even as the economy recovers – that the government’s main weapon against inflation will be its own spending. Think of this as a piece of reverse-Keynesianism.

- Take action to ensure that today’s secondary bubble in the housing market is not allowed to inflate further. Plans to cut stamp duty, for example, should definitely be put on hold. We don’t want housing prices to fall too fast, but neither should they be allowed to rise above today’s totally unsustainable levels.

Second, the government needs to get stuck into the Eurozone crisis, as I recommended in my post on Europe earlier this week, when I recommended that it should be:

…aiming for (in order of preference): (i) A strengthening of the Euro with greater sharing of economic sovereignty among Eurozone members (but with the UK left on one side); or (ii) An orderly removal of the weaker economies from the single currency.

Even on the Euro, the UK has some influence as an honest broker, given its position as an interested party, but not a full player. Cameron should adopt this role wholeheartedly – reminding British voters that the disorderly breakup of the single currency would be absolute disaster for the UK economy.

Third, we need to get the G20 back on track.

It briefly emerged as the forum for tackling the global economic crisis, but has now gone AWOL for, I suspect, a number of reasons:

- Obama is embroiled in a political system that cannot make foreign policy decisions.

- The Chinese are still bruised after Copenhagen.

- The Eurozone powers have utterly lost their nerve, and

- The Brits have left the field as the election approached.

Only the G20 has any hope of steering the global economy through what seem certain to be some exceptionally rocky times. If it is allowed to become a hopeless talking shop like the G8, then I think we are probably screwed.

Over the next year or so, the UK’s G20 policy will be its foreign policy. It’s essential that we have some radical new ideas to put on the table.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 6, 2010 | Global system, UK

It’s a fitting end to the British general election.

We have had thirty years of entrenched majorities – as a dominant party defined the terms of the debate, and the media made sure the opposition never caught a break. In 1997, the swing from Conservative to Labour dominance was sudden and decisive.

Now we have an utterly unpredictable polling day. Tiny shifts in the share of vote between parties and, especially, its geographical distribution could have a disproportionate impact on the political landscape that emerges on Friday.

If it’s close, it will all come down to spur-of-the-moment decisions by three very tired men. Constitutionally, Brown remains Prime Minister until someone else can command ‘the confidence of the House.’

As incumbent, he also should get first dibs on forming a new government, though it is widely expected that Cameron will declare victory early, and use the media to establish his right to govern.

As Alex has warned, there’s also a possibility that the bond markets will push the pace, as they open at 1 a.m. tomorrow morning to react to election news. Yields on UK 10-year bonds have spiked this morning, but are still lower than they have been for much of the year.

If Cameron gets the most votes and the most seats, he’ll surely go on to form a government. If not, a period of Florida-style uncertainty seems more than possible. What, one wonders, will be the UK’s equivalent of the hanging chad?

Either way, we can expect some exceptionally close Commons votes, perhaps a referendum on electoral reform, and – surely – a Parliament that won’t last for a full term. That means more elections for parties that have bankrupted themselves during this one.

This unaccustomed volatility in the electoral system seems curiously appropriate. As the past few years have shown, we now live in an era where the UK is far from being in control of its own destiny.

Look forward and we can expect the following forces to frame the government’s strategic choices.

First, global risks will continue to drive domestic policy. Voters will not actively call for a more effective foreign policy, but they will notice and bemoan its absence.

Global forces will continue to have considerable impact on their lives, with the main sources of strategic surprise coming from beyond the UK’s borders.

Over the next ten years, moreover, most risks will be on the downside. We have lived, as I have argued, through a volatile decade. There is every reason to expect risks to continue to proliferate.

Each new crisis will create political aftershocks with demands for governments to clear up the mess, matched by inquiries into why they failed to prevent the problem in the first place.

Finally, the government will find that, in most cases, it does not have the levers to manage risks as effectively as it would like to.

Whatever the next Prime Minister wants to do, he is going to find that global volatility, a lack of money, and government mechanisms that are equipped for the problems of another age, constrain his scope for action.

On top of that, he’ll only be able to solve problems if he can rustle up a coalition of other countries, all of whom will be beset by the same problems.

If – and it’s a big if – there is to be a new dominant paradigm in British politics, replacing those established by Thatcher and New Labour, then it will be because a leader emerges who has the skill to govern well in an age of global uncertainty.

I can’t imagine a more exciting time to pitch up in Downing Street, but it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 5, 2010 | Europe and Central Asia, Global system, UK

Early today, I pointed out some of the difficulties Europe could cause David Cameron in his early months as PM (should he form either a minority government, find himself leading a coalition, or win a majority tomorrow).

But what would a positive agenda for a new Conservative (or Conservative-led) government look like on the EU, given (i) the dreadful problems facing the Euro (a debt crisis from which sterling is not immune); (ii) broader strains in global strains (fall out from the financial crisis, growing competition for resources, nuclear proliferation etc.); (iii) the Conservatives’ historic ambivalence about the European Union?

Here are six pointers for Cameron, should he become PM.

First, get stuck into the Eurozone crisis aiming for (in order of preference): (i) A strengthening of the Euro with greater sharing of economic sovereignty among Eurozone members (but with the UK left on one side); or (ii) An orderly removal of the weaker economies from the single currency.

Even on the Euro, the UK has some influence as an honest broker, given its position as an interested party, but not a full player. Cameron should adopt this role wholeheartedly – reminding British voters that the disorderly breakup of the single currency would be absolute disaster for the UK economy.

Second, recognise the severe dangers posed to the UK by a loss of cohesion in European societies.

It is tempting, but foolish, to see a breakdown in social order in Greece as only being a peripheral issue, or to fail to take seriously signs of a loss of trust between ethnic and religious groups across a number of European countries.

Maybe this is just a passing blip, but if I was Cameron I’d accept that it only makes sense to talk about a resilient nation within the context of a resilient European neighbourhood. We live in an era where social movements hop borders with ease. The last thing the UK needs is to get sucked into an era of riots, strikes and violence within its communities.

This may be a low probability/high impact threat to British national security, but we all remember a time when global economic collapse was regarded as so unlikely it wasn’t worth planning for, don’t we?

Third, pursue a vision of turning Europe into an outward-facing platform for managing global risks.

As Alex and I have argued, globalization is in the early stages of what is likely to prove a ‘long crisis’. The UK has made a one-way bet on a rules-based international order and we need to fight for our interests in this wager (even though meaningful progress on most issues is going to be hard to achieve).

The world is now shooting the rapids. The new government must be a clear and consistent voice arguing for Europeans to start looking outwards, making whatever contribution we can to charting a course through turbulent waters.

Another era of navel gazing is the last thing the EU can afford.

Fourth, accept that the development of a multi-layered Union is now inevitable, with the EU running at different speeds and on different tracks.

This could be good for the UK, if we: (i) don’t sulk on the sidelines; (ii) see that a distanced-but-engaged stance will often make us a more attractive partner (e.g. for the French, as they seek to balance German hegemony); (iii) take an extremely active leadership role on policy issues that matter most to the UK, compensating for times when we choose not to get involved.

Finally, become an intelligent advocate for subsidiarity.

It should be absolutely clear that Europe is yet to work out which issues need to be managed at European, national, or more local levels. But, so far, the Eurosceptic position on this has won few friends, coming across as unconstructive and lacking nuance to many Europeans.

But that could change if Cameron is prepared to reframe Euroscepticism as an ongoing search for a more balanced, flexible and adaptable union between European nations.

Carefully tuned, that message could resonate well with at least some of our European partners, while also helping Cameron triangulate divergent camps at home, including the pro and anti-European factions on his own backbenches.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by David Steven | May 5, 2010 | Europe and Central Asia, UK

This morning sees early evidence of the difficulties David Cameron will face on Europe, if he ends up leading a minority government or has a very slim majority.

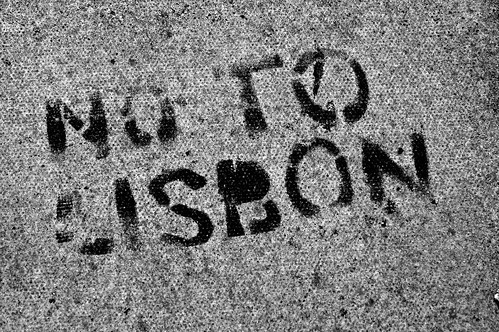

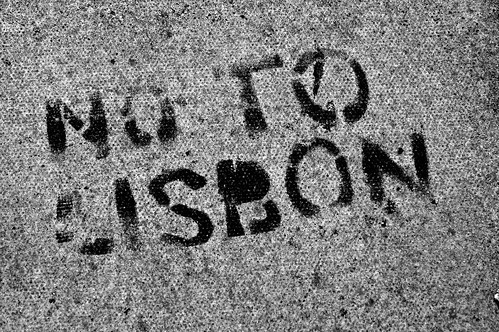

The Spanish presidency has set out proposals to amend the Lisbon Treaty in order to allow 18 additional MEPs to take up their seats (read Bruno Waterfield for background). The Conservative Party’s Eurosceptic wing sniffs an opportunity: maybe this will allow a new PM to throw the entire treaty back up in the air.

The Taxpayers’ Alliance leads the charge:

It has been widely assumed that the hope of a Lisbon Treaty referendum was dead and buried, but this development brings it back to the fore. David Cameron has always claimed that had he been in Government when the Lisbon Treaty passed through Parliament then he would have held a referendum. Will he now promise to hold a referendum on this new version of the Lisbon Treaty if he is in charge after the General Election? […]

Grasping this opportunity would be popular, strategically shrewd and – perhaps most importantly of all – honourable to the spirit as well as the letter of the Conservatives’ EU pledges. The failure to grasp it would not only be astonishingly shortsighted; it would be the final brutal betrayal of the pledges made to the British people in a general election – the election of 2005.

ConservativeHome weighs in, to great excitement in its comments, while England Expects mutters darkly about an entirely new Lisbon Treaty being ‘rammed’ through both Houses of Parliament.

This is a storm in a teacup, it seems to me – but it’s a sign, surely, of battles to come.

If he emerges from the election as PM, I expect David Cameron will need votes from Labour and Lib Dems if he is to avoid a series of fruitless rows with the UK’s European partners.

[Read the rest of our After the Vote series.]

by Alex Evans | May 3, 2010 | UK

Goes like this (read the whole thing):

Picking a modern leader boils down to a question of which false persona you prefer. At least Brown’s is almost admirably crap. It’s easy to see through it and catch hints of something awkwardly, weakly human beneath.

Clegg’s persona is roughly 50% daytime soap, 40% human, and 10% statesman. Cameron is 100% something. He isn’t even a man; more a texture-mapped character model. There’s a different kind of software at work here, some advanced alien technology projecting a passable simulation of affability; a straight-to-DVD retread of the Blair ascendancy re-enacted by androids. Like an ostensibly realistic human character in a state-of-the-art CGI cartoon, he’s almost convincing – assuming you can ignore the shrieking, cavernous lack of anything approaching a soul. Which you can’t.

I see the sheen, the electronic calm, those tiny, expressionless eyes . . . I glimpse the outlines of the cloaking device and I instinctively recoil, like a baby tasting mould. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t see a power-crazed despot either. I almost wish I did. Instead, I see an avatar. A simulated man with a simulated face. A humanoid. A replicant. An Auton. A construct. A Carlton PR man who’s arrived to run the country, and currently stands before us, blinking patiently, blank yet alert, quietly awaiting commencement of phase two. At which point, presumably, his real face may finally become visible.