by Seth Kaplan | Mar 13, 2012 | Conflict and security, Economics and development, Middle East and North Africa

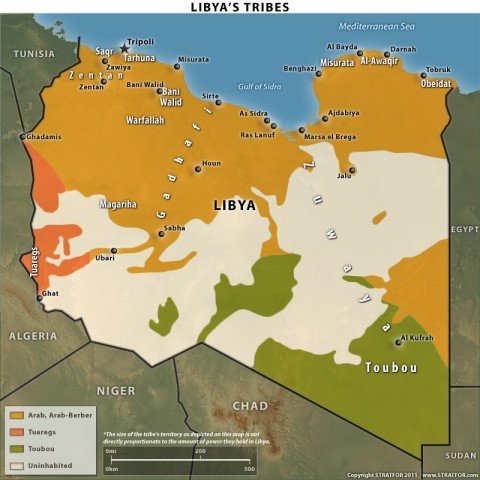

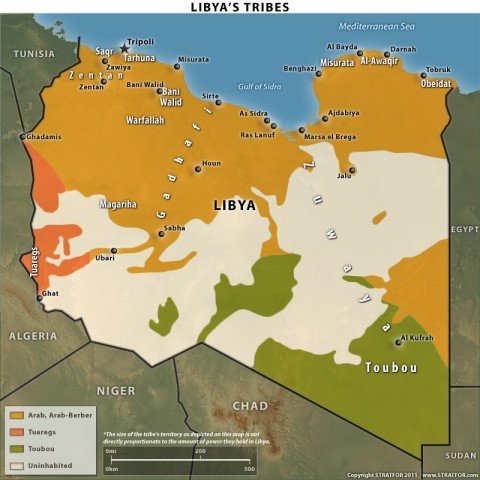

Last week, 3,000 militia and tribal leaders from eastern Libya announced unilateral plans to begin establishing their own autonomous government. They demanded a return to the loose federation that existed before Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi came to power in 1969.

Predictably, the leaders of the National Transitional Council (NTC) in Tripoli rejected these calls. Mustafa Abdel Jalil, head of the National Transitional Council, even claimed that they were inspired by elements loyal to Gaddafi’s old regime.

This is a mistake. Although Libya would in an ideal world be just fine with a unitary government built around a single national assembly, it is more likely to create a robust state that can meet the needs of its people if it empowers its regions. (more…)

by Seth Kaplan | Mar 12, 2012 | Conflict and security, Economics and development

Social cohesion is an underappreciated but crucial element in development, state building, and poverty reduction.

It is an especially important factor in determining whether a state is fragile or not. As I argued in Fixing Fragile States:

Two factors above all others decide how a country’s political, economic, and societal life evolves: a population’s capacity to cooperate (which depends, for the most part, on the level of social cohesion) and its ability to take advantage of a set of shared, productive institutions (especially informal institutions at the crucial early stages of development when formal institutions are usually feeble and ineffectual). . . . These two ingredients shape how a government interacts with its citizens; how officials, politicians, and businesspeople behave; and how effective foreign efforts to upgrade governance will be. Together with the set of policies adopted by the government, they make up the three major determinants of a country’s capacity to advance.

Fragile states are deficient in both these areas. And the combination of political identity fragmentation and weak national institutions works in a vicious cycle that severely undermines the legitimacy of the state, leading to political orders that are highly unstable and hard to reform.

But social cohesion has rarely attracted the attention it deserves from the development community. Dependent on sociopolitical factors that are hard to measure, analyze, and understand, it holds no prominent place in any international agency’s programming. Like almost everything related to the “software” of how states work, it is all too easily ignored.

This may be changing at least at the margins—in conferences and reports. The World Bank, for instance, is using it to discuss jobs in its forthcoming World Development Report. And the OECD recently published Perspectives on Global Development 2012: Social Cohesion in a Shifting World.

This is progress of a sort, but these conferences and reports are missing something important. Instead of seeing social cohesion as a “complex cultural, psychological and social phenomenon,” as Duncan Green put it on his blog earlier this year, they look at economic issues and technocratic solutions. The OECD report, for instance, promotes redistribution via progressive tax reform and increased and more pro-poor public spending; investment in education; protecting poor people against volatility via social protection and improved labor market institutions such as the minimum wage.

There is nothing particularly wrong with most of this agenda, but it does not get to the heart of the matter. A country with high levels of social cohesion would likely have a leadership with an interest in introducing programs that helped the poor. A country that had little social cohesion would likely have a leadership that had little interest in helping the poor. These proposals matter far less than trying to figure out what affects elite attitudes and what might be done to make elites feel that the poor is “one of us.” (more…)

by Seth Kaplan | Feb 27, 2012 | Africa, Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence

In the aftermath of the conference in London on Somalia, I offer a wrap-up of the best articles and books to read on the country.

In the past week, there has been a number of excellent pieces on what the international community has done wrong in the past, and how it might do better going forward.

In general, they all suggest that the focus should be on what is working—in places such as Somaliland, Puntland, and Galmudug—rather than on any foreign blueprint for success.

Past initiatives have repeatedly attempted to impose a centralized bureaucratic governing structure on the country, a structure ill-suited to Somali society. Such efforts have never been effective and have only aggravated domestic tensions. (more…)

by Seth Kaplan | Feb 16, 2012 | Economics and development

There have been growing demands for greater independent evaluation of foreign aid for at least half a decade now. As William Easterly argued as far back as 2006:

We need independent evaluation of foreign aid. It’s amazing that we’ve gone a half century without this. . . . [Truly independent evaluation of aid would] give feedback to see which interventions are working and give incentives to aid staff to find things that work.

The Center for Global Development summarized the need in its report When Will We Ever Learn? Improving Lives Through Impact Evaluation:

Impact evaluations do not have to be conducted in-house. Indeed, their integrity, credibility, and quality is enhanced if they are external and independent.

It is with this understanding that I read the recent Brookings report on aid to fragile states. (more…)

by David Steven | Oct 20, 2010 | Conflict and security, Economics and development, UK

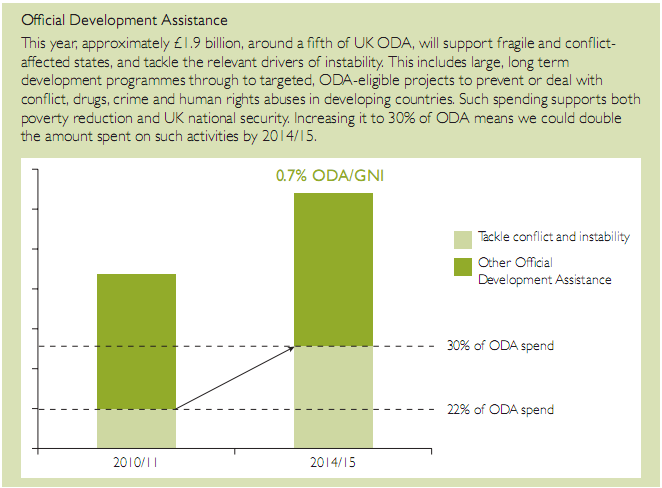

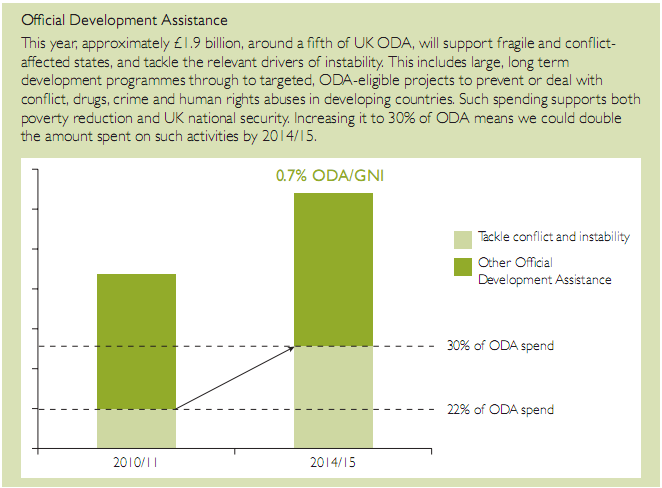

For DFID – the heart of yesterday’s defence review was a new commitment to spend 30% of Britain’s development cash on “priority national security and fragile states”. This box explains what that means in cash terms…

Alex and I argued for this policy in our Chatham House paper. DFID, we wrote, should be turned into the world leader in tackling the problems of fragile states.

But there was a quid pro quo. Fragile states need lots and lots of high-level expertise – not oodles of dosh. But DFID is probably going to be forced to make job cuts as a result of the spending review. So it’s going to have more money, tougher challenges to deal with, but fewer people. Something has to give.

The solution, we argued, was for the government to “make it clear that where a poor country’s main need is financial, the UK will not necessarily maintain a country office – but will instead reduce transaction costs by partnering with other effective donors, or simply channeling funds through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.”

So far, the coalition has seemed fairly cool on the multilateral system – but if it wants to do a good job in fragile states, this has to change. Clearly, the FCO and MOD are hoping they will directly spend a big chunk of the UK’s development money, but DFID still needs to think hard about how best to deploy is scarcest resource – the expertise of its dwindling staff…