by David Steven | Oct 19, 2012 | Economics and development, UK

Global Dashboard, November 2011:

But let’s go back to the poverty MDG. In 1990, there were 1.8 billion poor people (in a world of 5.3bn people). If the IMF/Bank projections pan out, by 2015, there’ll be 882.7m poor people left (in a world of 7.3bn). That represents real progress in both relative and absolute terms.

Here’s a thought. In the debate about what should succeed the MDGs, one obvious option is simply to extend the current set of goals and focus harder on the challenges facing the 15% of the world’s population that will still be below the poverty line in 2015.

If poverty does indeed fall by a billion between 1990 and 2015, then there’s no reason why it shouldn’t fall as fast over the next fifteen years, even as the global population grows by another billion. In other words, having halved absolute poverty, leaders could commit to abolishing it by 2030.

DFID’s most senior official, October 2012:

When they were first proposed in the 1990s, the MDGs were widely thought too ambitious and aspirational to be taken seriously. The pundits thought that halving the proportion of people living under a dollar a day, sending every child to school, reducing under-5 mortality by two thirds and maternal mortality by three quarters, all by 2015, was pie in the sky.

As we now know, the sceptics have been confounded…

So when my Prime Minister said in New York last month that the international community should aim to abolish extreme poverty within this generation, our generation, these were not just aspirational words. Abolishing extreme poverty within our lifetimes is absolutely within our grasp.

Three questions for development organisations now: (i) What exactly have they contributed to poverty reduction or would change have been as rapid without them? (ii) What is their theory of change for helping the poorest people in the world’s toughest operating environments? (iii) How does that theory of change need to evolve given new realities (for example, that in many countries, we will have the name and address of every poor family)?

by Seth Kaplan | Apr 12, 2012 | Economics and development

As the competition for president of the World Bank approaches its final stages, it is worth considering what changes ought to be brought in by the new person. One area in need of reform is the Bank’s system of country classifications. Although Robert Zoellick pushed the World Bank to open its much-prized treasure chest of data to the public during his five-year term as president, he did little to reform how the World Bank conceptualized that data. Changing how countries are classified would have a wide impact on the whole development community.

For instance, look at all the discussion in development policy circles about the sharp reduction in the number of low-income countries in recent years. Some believe this news should be trumpeted as a policy success. For others, the reduction suggests that there is a “New Bottom Billion” of poor people living in middle-income countries, forcing a change in donor focus. For yet another group, it indicates that foreign aid as a concept should be updated to blend more loans with grant money.

But has all that much changed? Does the World Bank country classifications accurately identify the countries in need of outside assistance? (more…)

by David Steven | Oct 20, 2010 | Conflict and security, Economics and development, UK

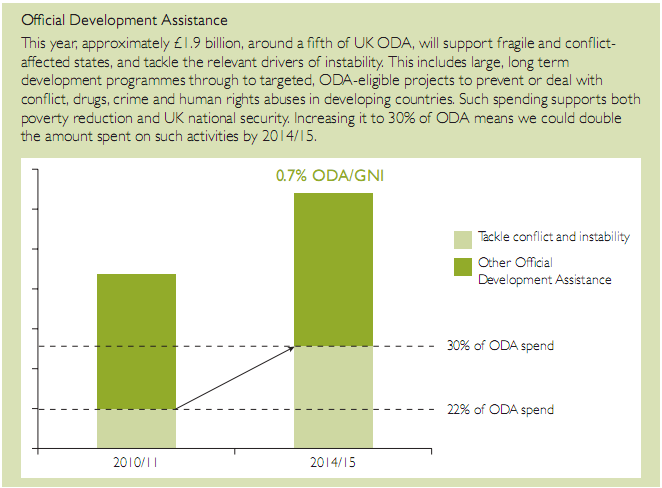

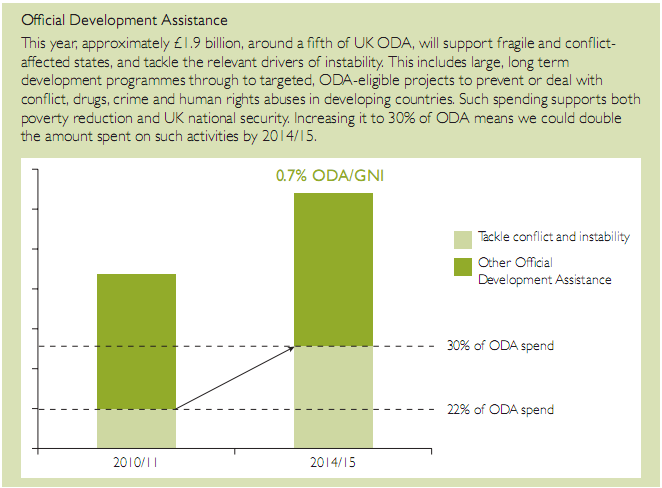

For DFID – the heart of yesterday’s defence review was a new commitment to spend 30% of Britain’s development cash on “priority national security and fragile states”. This box explains what that means in cash terms…

Alex and I argued for this policy in our Chatham House paper. DFID, we wrote, should be turned into the world leader in tackling the problems of fragile states.

But there was a quid pro quo. Fragile states need lots and lots of high-level expertise – not oodles of dosh. But DFID is probably going to be forced to make job cuts as a result of the spending review. So it’s going to have more money, tougher challenges to deal with, but fewer people. Something has to give.

The solution, we argued, was for the government to “make it clear that where a poor country’s main need is financial, the UK will not necessarily maintain a country office – but will instead reduce transaction costs by partnering with other effective donors, or simply channeling funds through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.”

So far, the coalition has seemed fairly cool on the multilateral system – but if it wants to do a good job in fragile states, this has to change. Clearly, the FCO and MOD are hoping they will directly spend a big chunk of the UK’s development money, but DFID still needs to think hard about how best to deploy is scarcest resource – the expertise of its dwindling staff…

by Alex Evans | Oct 12, 2010 | Economics and development, Global Dashboard, UK

I gave a presentation this morning on global challenges to development for the UK International Development Select Committee, which has a new line-up of members following the general election. Here it is…

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 23, 2010 | Economics and development, Global Dashboard, UK

Amid the whirlwind of papers published to coincide with the MDG Summit in New York this week, there’s one that you absolutely must read: this report by Andy Sumner from the Institute of Development Studies, which argues that most of the world’s poor people no longer live in poor countries (i.e. low income ones – which the World Bank defines as those in which annual per capita income is less than $995). Here’s the punchline:

In 1990, we estimated that 93 per cent of the world’s poor people lived in low income countries (LICs). In contrast, in 2007-08 we estimate that three quarters of the world’s approximately 1.3 bn poor people now live in middle income countries (MICs) and only about a quarter of the world’s poor – about 370m people – live in the remaining 39 low income countries, which are largely in sub-Saharan Africa.

Andy’s findings are a very big deal, because they directly affect the question of where the UK should concentrate its development resources – and strongly call into question a core pillar of DFID’s current approach.

When I arrived at DFID as a novice Special Adviser in 2003, the department was hugely enthusiastic about a target of spending 90% of the UK’s aid in low income countries (the so-called ’90-10 target’).

This was in turn based on research by two economists, David Dollar and Paul Collier, which argued that to get most bang for your buck with your aid, you should concentrate it on good-performing (as opposed to fragile) low income countries (see this 1999 World Bank paper of theirs for more). This argument got a warm reception among senior DFID officials and the main development NGOs – in particular because so many of them adhered to a development paradigm that emphasised spending money as the key means of delivering poverty reduction.

One corollary of the Dollar-Collier argument was that fragile or conflict-affected low income countries were seen as offering less good rates of return on aid. While DFID more or less bought that argument in 2003, it largely reversed its position after that as it internalised what conflict does to prospects for poverty reduction and development, particularly from DFID’s 3rd White Paper in 2006 onwards. (And, as Richard noted in a recent post, new International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell looks set to continue that process.)

But the other corollary of the Dollar-Collier thesis was that middle income countries were also seen as less effective places to target UK aid – an issue that came to a head in 2003, when DFID came under huge pressure from Number 10 to increase massively its spending in Iraq, a middle income country.

Hilary Benn had been in post as Secretary of State for literally a few hours when he faced the decision of which programmes would have to be cut – and, by extension, whether DFID would maintain the 90-10 target. The NGOs we consulted were categorical: if DFID dropped the target, they would regard it as an act of war.

So with Number 10 demanding cash for Iraq on one hand and NGOs demanding the 90-10 target on the other, there was only one way to satisfy both: a veritable bonfire of middle income country programmes other than Iraq. Many programmes had their budgets slashed to the bone; many more had their offices closed altogether (see this Guardian coverage from the time).

Of course, all this was seven years ago, back in those strange days immediately after the invasion of Iraq. But bear in mind that 2003 proved to be the starting gun on a process that has continued since then, and which will soon reach its logical conclusion – when DFID closes its China programme. Andy’s research poses the question: is this actually what we should be doing?

Of course, the obvious counter-argument is that that it’s ridiculous for the UK to be sending aid to, say, China when China has its own aid programme in Africa. And if – like Dollar and Collier in 1999 (or, one might argue, like Bono or Jeff Sachs today) – you think development is primarily about spraying money at poor countries, then that’s entirely logical.

But the point is that there’s more to development that just disbursing aid money. As I argued in a post last year (see also this one),

If we really want a full-spectrum approach to development, we need to place a bit less emphasis on aid and a lot more on political economy work in countries – the slow, steady process of using influence at the margins to work with progressive drivers of change towards pro-poor political outcomes in country.

That’s what DFID’s middle income country programmes were all about – and why it was such a tragedy to see them closed down. That’s why DFID needs to retain a sizeable staff presence in China, even if its budget there shrinks. And that’s why DFID’s people are as important as the size of its budget – and why it was so disastrous for DFID to lose one in six staff in “efficiency savings” under Labour, and why it will be nothing short of catastrophic if the same again happens under the current government.

Development policy needs to be about poor people, not just poor countries. Once we reframe our objectives in that light, we’ll find ourselves embarking on reconsideration of some fairly fundamental principles about how and where we do development.