Britain and Europe after the veto

What a day. Five observations:

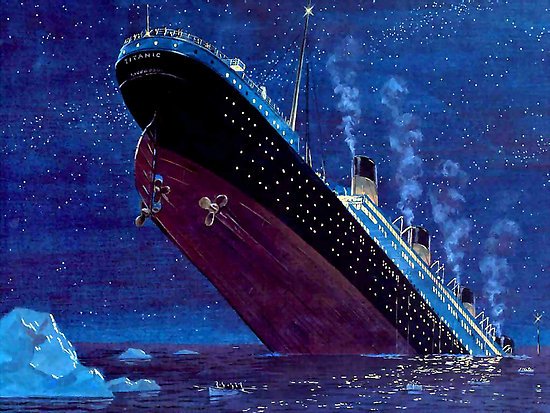

- My initial reaction this morning: On a sinking Titanic, the UK is lobbying to avoid further damage to the iceberg. If David Cameron was motivated mostly by his wish to suck up to the City (and to his backbenchers), then he deserves all that fate can throw at him. He has transformed eventual British exit from the EU from Eurosceptic fantasy to the new conventional wisdom in just 12 hours. Quite a feat.

- But maybe… his government has decided that the euro is now doomed and has made a rational decision to swim as far from the vortex as possible. Many believe that a disorderly break up of the single currency has become more likely than not. That would probably cost the UK 10% of GDP and make British default a near certainty. But if that’s what’s going to happen, then we better knuckle down to being as resilient to the shock as possible.

- The British veto makes euro failure more, not less, likely. In theory, agreement between a core group is easier than having all 27 countries in the room, but the legal complications of conjuring a new set of institutions from thin air are daunting. Also, expect the core to shrink as the summit’s aspirations are chewed up by domestic politics. Each defection will provide a potential trigger for wider breakdown – probably when a group of the strong decide all hope is lost, and make a collective rush to the lifeboats. By being the first to desert the ship, Cameron has made it much easier for other European leaders to follow.

- Contingency planning must now go much deeper. Behind the scenes, governments are playing out failure scenarios, and most big businesses have some kind of post-euro plan in place. Much of the thinking is still pretty rudimentary, however. The eurozone countries can’t risk letting markets see them flinch and have to put a brave face on their prospects, but the UK no longer needs to have such scruples. What exactly would we do if the euro goes down? What would be thrown overboard? What, and who, would be saved? How can the government organise effective collective action as the catastrophe hits?

- Nick Clegg is dead, politically. That was already true, but I can’t imagine even Miriam González Durántez now plans to support her husband at the next election. Paradoxically, accepting his terminal status could give Clegg new freedom of action. Instead of continuing to play the role of coalition gimp, he should offer leadership to those keen to explore what comes after the storm. Politicians with proper jobs – Cameron, Osborne, even Cable – are going to be overwhelmed by events throughout this parliament, even in the best case where Europe struggles back onto its feet. Clegg, though, has an opportunity to focus energy on the longer term. He’ll still lead the Lib Dems to electoral Armageddon, but catalysing a vision for renewal might make posterity a little kinder to the poor man.