by David Steven | Apr 12, 2012 | Economics and development, Influence and networks, UK

As David Cameron prepares to chair the High Level Panel charged with designing a successor to the Millennium Development Goals, he should be in no doubt that he faces a tough job.

The original goals have been remarkably successful. Even in a single organisation, most targets are agreed and then quickly forgotten. The MDGs, which took a decade to stitch together, have prospered since their final agreement in 2002. Most developing country governments, and nearly all donors, have at least partially aligned policies to them.

Poverty rates have also dropped remarkably quickly (and not just in China) and progress towards social development targets seems now to be accelerating. How much of the good news can be directly attributed to the MDGs is hard to prove. But if you accept that goals can only ever be a part of the answer to a complex problem, then the British PM should start by asking why the MDGs did so well, not by assuming that his Panel is easily going to come up with something better.

His first question should be to ask what makes for an effective set of goals. I’d identify five criteria. They should:

- Be resonant – powerful, simple and clear enough to communicate with politicians, media, public.

- Form the main elements of a common strategic language, enabling different types of organisation to understand and work with each other.

- Be amenable to implementation, not just on a technical level, but given likely political and resource constraints.

- Have sufficient authority and clarity that it matters whether or not they are delivered fifteen years down the road.

Conversely, effective goals avoid:

- Too much complexity – every interest group in the world will want ‘its’ target included and for technocrats more is usually more. Resisting a ‘Christmas Tree’ framework will require a willingness to pick tough political battles.

- Straying into areas where consensus doesn’t exist – goals make countries more likely to do difficult things they believe are in their best interests; they can’t be used radically to change their identification of those interests.

- Distorting incentives in a way that is significantly counterproductive. Goals will inevitably have at least some adverse consequences, but the detail and balance of the framework will determine how serious a problem this is, as will the quality of the data on results (to avoid cheating).

- Making promises that aren’t really meant – some countries will be happy to sign up to goals they have no intention of doing anything to meet and it is possible to imagine leaders embracing a set of empty promises in 2015 just so they can have a big announcement to make.

So my advice to David Cameron would be to take three types of failure very seriously:

- A failure to agree – lots of talk that leads, ultimately, to another multilateral car crash.

- A framework to forget – we get agreement in 2015, but it’s largely ignored thereafter.

- A strategic realignment to no great purpose – we get goals, try to implement them, but it doesn’t work out due to a lack of will or because the goals are the wrong ones.

None of this is to say that I think that, as Chair of the Panel, the PM has been handed (or worse, lobbied for) a poisoned chalice. Sequels are usually worse than the original, precisely because of the complacent assumption that the original’s success will easily be replicated. Cameron – and his team – need to make it clear from the beginning that they are intent on avoiding this error.

(This post is based on a talk I gave to a seminar recently at Brookings. Alex and I will publish a Brookings paper on the post-2015 challenge in the next few days.)

by Alex Evans | Apr 12, 2012 | Economics and development, Influence and networks, UK

News in the Guardian today:

David Cameron has been asked by the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, to chair a new UN committee tasked with establishing a new set of UN millennium development goals to follow the present goals, which expire in 2015.

Some initial reactions:

– It’s a major political coup for the UK, and especially of course for DFID, who’ve been working behind the scenes to secure this outcome for months. (The UK may not have been supposed to announce the appointment just yet – there’s nothing on the appointment in the last briefing of the Secretary-General’s spokesman – but you can see why they couldn’t wait…)

– The immediate question now is who will be the other co-chair – or co-chairs. Two co-chairs is the norm for this kind of UN exercise, one from a developed and one from a developing country, but three co-chairs is not unheard of (e.g. the 2006 High-level Panel on System Coherence). If there were three, expect one to be from an emerging economy and one from a low income country.

– It’ll be safe to assume that the other co-chair[s] will be serving heads of government too. If I had to make a guess right now on people, I’d go for Dilma Rousseff from Brazil as the emerging economy candidate (especially as the Rio+20 summit in June is the launchpad for the Panel), and maybe Ellen Johnson Sirleaf from Liberia. Meles Zenawi would be another obvious choice, but he chaired a recent UN panel on climate finance so may be out of the running, plus the UN will want to have gender balance among the co-chairs.

– Another big question is who will head up the secretariat that supports the Panel. The recent trend has been for the secretariat head to come from within the UN: this was the case on both the Global Sustainability Panel last year (which I worked on), and the 2006 system coherence panel). But there’s also precedent from them to come from outside (Steve Stedman’s role on the 2004 panel on Threats, Challenges and Change being the obvious example).

– In terms of substance, the direction of the post-2015 agenda is currently heading towards the idea of Sustainable Development Goals. The Rio+20 summit will probably call for SDGs as a key summit outcome, but duck the issue of what those Goals should cover – passing the political heavy lifting straight to the Panel that David Cameron will be co-chairing.

– Expect the politics of this agenda to become very challenging and complex over the next 12-18 months. We did a backgrounder on SDGs a couple of months ago, which gives a quick overview; we’ll also be publishing a more up-to-date analysis paper through the Brookings Institution very shortly.

– On the domestic political aspects, Patrick Wintour’s analysis in the Guardian is undoubtedly right that this will firmly lock in the government’s commitment to spending 0.7% of national income on aid. At the same time, David Cameron’s chairmanship of the Panel will also allow him to argue to domestic audiences that he’s pushing internationally for a more hard-headed approach to aid – an argument that Conservative Home is already running with approvingly.

Update: if you’re wondering about how David Cameron sees the development agenda, take a look at this speech from last year.

by David Steven | Dec 9, 2011 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, UK

What a day. Five observations:

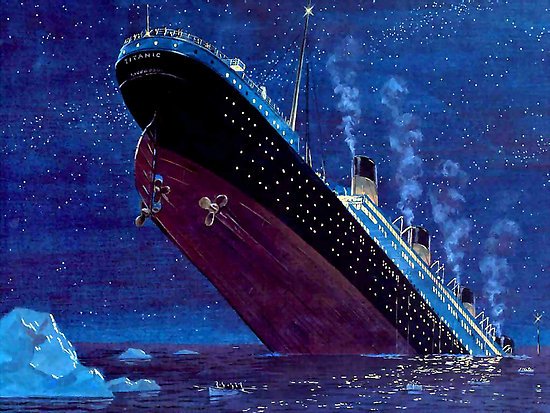

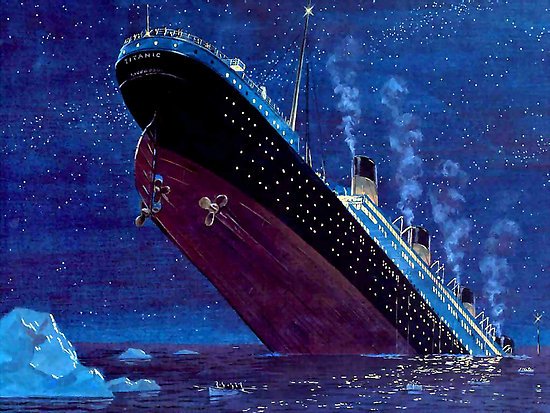

- My initial reaction this morning: On a sinking Titanic, the UK is lobbying to avoid further damage to the iceberg. If David Cameron was motivated mostly by his wish to suck up to the City (and to his backbenchers), then he deserves all that fate can throw at him. He has transformed eventual British exit from the EU from Eurosceptic fantasy to the new conventional wisdom in just 12 hours. Quite a feat.

- But maybe… his government has decided that the euro is now doomed and has made a rational decision to swim as far from the vortex as possible. Many believe that a disorderly break up of the single currency has become more likely than not. That would probably cost the UK 10% of GDP and make British default a near certainty. But if that’s what’s going to happen, then we better knuckle down to being as resilient to the shock as possible.

- The British veto makes euro failure more, not less, likely. In theory, agreement between a core group is easier than having all 27 countries in the room, but the legal complications of conjuring a new set of institutions from thin air are daunting. Also, expect the core to shrink as the summit’s aspirations are chewed up by domestic politics. Each defection will provide a potential trigger for wider breakdown – probably when a group of the strong decide all hope is lost, and make a collective rush to the lifeboats. By being the first to desert the ship, Cameron has made it much easier for other European leaders to follow.

- Contingency planning must now go much deeper. Behind the scenes, governments are playing out failure scenarios, and most big businesses have some kind of post-euro plan in place. Much of the thinking is still pretty rudimentary, however. The eurozone countries can’t risk letting markets see them flinch and have to put a brave face on their prospects, but the UK no longer needs to have such scruples. What exactly would we do if the euro goes down? What would be thrown overboard? What, and who, would be saved? How can the government organise effective collective action as the catastrophe hits?

- Nick Clegg is dead, politically. That was already true, but I can’t imagine even Miriam González Durántez now plans to support her husband at the next election. Paradoxically, accepting his terminal status could give Clegg new freedom of action. Instead of continuing to play the role of coalition gimp, he should offer leadership to those keen to explore what comes after the storm. Politicians with proper jobs – Cameron, Osborne, even Cable – are going to be overwhelmed by events throughout this parliament, even in the best case where Europe struggles back onto its feet. Clegg, though, has an opportunity to focus energy on the longer term. He’ll still lead the Lib Dems to electoral Armageddon, but catalysing a vision for renewal might make posterity a little kinder to the poor man.

by David Steven | May 19, 2011 | Europe and Central Asia, Middle East and North Africa

No-one reads The Independent, but – even so – Downing Street is sure to be steaming at tomorrow’s front page:

by Michael Harvey | Jul 30, 2010 | Climate and resource scarcity, Cooperation and coherence, East Asia and Pacific, Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, South Asia, UK

– Over at The Diplomat, Thomas Wright explores how China’s self-confidence in initial relations with the Obama administration may prove the “catalyst for a more competitive – and geopolitically savvy – US multilateralism.” Der Spiegel, meanwhile, highlights the extent of Chinese soft power, while Charles Grant sees a chance to enhance the EU’s relations with the emerging superpower.

– Focusing on Chinese domestic society, the Economist highlights the growing activism and changing dynamics of the country’s vast labour force, with its associated implications for the global economy. Analysis over at VoxEU, meanwhile, assesses evidence of a potential Chinese property bubble.

– Elsewhere, with David Cameron back from his visit to India, Adrian Hamilton and Geoffrey Wheatcroft offer their views on his approach to international affairs. Kim Sengupta meanwhile remarks that the new Prime Minister “has started his foreign policy journey with a series of very deliberate steps”.

– Finally, Sir John Sulston talks to the New Scientist about the implications of global population change for sustainable development – the subject of a new initiative that he’s leading for The Royal Society. Prospect Magazine‘s blog, meanwhile, highlights favourable demographic trends in the developing world, while figures this week confirm that the EU’s population has now passed the 500 million mark.