Eyjafjallajökull – finally (we hope) farce

So the UK’s airspace is open again after the Civil Aviation Authority issued this rather plaintive statement:

The CAA has drawn together many of the world’s top aviation engineers and experts to find a way to tackle this immense challenge, unknown in the UK and Europe in living memory.

Current international procedures recommend avoiding volcano ash at all times. In this case owing to the magnitude of the ash cloud, its position over Europe and the static weather conditions most of the EU airspace had to close and aircraft could not be physically routed around the problem area as there was no space to do so.

We had to ensure, in a situation without precedent, that decisions made were based on a thorough gathering of data and analysis by experts. This evidence based approach helped to validate a new standard that is now being adopted across Europe.

The major barrier to resuming flight has been understanding tolerance levels of aircraft to ash. Manufacturers have now agreed increased tolerance levels in low ash density areas.

The no-fly zones – if they are the same agreed by Eurocontrol – are a few tiny patches of sky, leaving the media increasingly convinced that the past week has been a to-do about nothing (cf. BSE, swine flu).

With the crisis seemingly ending in farce, let’s hope there’s not a final tragic act (a plane loses an engine or falls out of the sky) or sequel (Katla erupts). If that happens, journalists will swiftly execute a U-turn – to complain that governments have been reckless in putting passengers’ lives at risk, or have failed to equip the world’s aircraft with the sensors that can keep them flying when ash is in the air.

It’s still not clear to me how a few test flights – which one expert yesterday derided as evidentially useless – have allowed a safe level of ash for jet engines. According to the Guardian, however, there has been a tussle over the issue that long pre-dates this crisis, with industry (afraid of legal action) previously arguing for a rigid application of the precautionary principle.

When the inevitable enquiry is announced, I hope it is given a broad remit to look at how European society responded to the crisis, and not just be charged with focusing on technical issues.

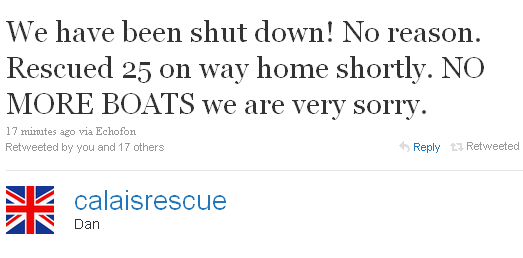

As I have argued on Saturday morning, governments allowed themselves to get behind the curve on the crisis and never recovered; the media was always uncomfortable with the issue (until it settled on someone to blame); while the public response (including widespread use of social media) tells us a lot about how we are and are not resilient in the face of crisis.

All these aspects should be studied by the enquiry team.

In the UK. a lot of attention will quite rightly focus on how three organisations worked together – the CAA, NATS (the air traffic controllers), and the Met Office. While it is hard to know what went on behind the scenes, in public, the relationship between the three seemed increasingly strained.

At the start of the crisis, NATS was very happy to be in the lead. Over time, it became increasingly keen to pass the buck, underlining that it was only following advice given it by its fellow members of the ‘no fly’ triad.

Communication from the three organisations was woeful, in marked contrast with the much more proactive approach of Eurocontrol. I fail to understand why Ministers did not force them to run regular joint press conferences – and to establish a shared web portal (backed up by a Twitter feed) to provide regular and comprehensive updates.

Here’s a thread I think the enquiry might like to pick at, taking it into the opacity and vagueness of official communications. What on earth happened to the mysterious ‘second cloud’ that NAS was warning us about only the night before last?

Since our last statement at 1530 today, the volcano eruption in Iceland has strengthened and a new ash cloud is spreading south and east towards the UK. This demonstrates the dynamic and rapidly changing conditions in which we are working. Latest information from the Met Office shows that the situation is worsening in some areas.

I never saw any other evidence that this new cloud really existed (though perhaps it did) – but its existence was unquestioningly reported by media on both sides of the Atlantic. How, if the situation was worsening, could airspace be reopened just 24 hours later?

For all Global Dashboard coverage of the crisis – click here. Plus some risk management lessons from the Economist. Also, John Kay. And Sue Cameron gives Lord West a pasting for deploying the navy.