by David Steven | Nov 24, 2008 | Global system

The Citibank rescue is being described as a ‘good bank/bad bank‘ deal. Not so, says Paul Kedrosky:

Here is the gist:

- Citi will carve out $300-billion in troubled assets, which will remain on its balance sheet:

- The first $37-$40-billion in losses on those assets will go to Citi

- The next $5-billion in losses will hit Treasury

- The next $10-billion in losses will go to the FDIC

- Any more losses will go to the Fed

- There will be no management changes at Citi, because, you know, they are all fine and upstanding people who have done nothing wrong.

- There will be some compensation limitations, but those have not yet been made clear.

To be clear, this is not a “bad bank” model. Assets are not, apparently, being taken off the Citi balance sheet and put into another entity walled off from the Citi biological host. Instead, they are being left on the Citi balance sheet, but tagged and bagged for eventual disposal via taxpayers.

He dubs it the ‘fucked bank’ model.

Update: John Carney likes the deal (not):

Citi shovels a steaming pile of $306 billion of crap assets into a corner of its balance sheet. It gradually writes down their value. Citi takes the first $29 billion of losses, and taxpayers take the next 90% (about $250 billion). In exchange, taxpayers get $27 billion of Citi preferred stock.

Would Warren Buffett have made that deal? No way.

At the very least, there should be a sliding scale for taxpayer ownership: The more the value of the crap assets deteriorates, the more of the company the taxpayers own (and the government should be assessing the value of these assets, not Citigroup). Because as it is, Citi has an incentive to write the whole pile off tomorrow for a song. (This would actually be good for the economy, but not for the taxpayer’s “investment”).

By the way, there is no guarantee that this taxpayer largesse will save Citigroup. $306 billion of assets sounds like a lot, but it’s only about 15% of Citi’s massive asset pile (10% if you count the stuff that was so hideous that Citi shoveled it off the balance sheet long ago). Presumably Citi could keep having to take writedowns on assets outside of the bailout’s $306 billion, weakening the company’s capital and eventually possibly forcing yet another bailout.

So taxpayers may get yet another chance to get hosed.

Update II: This from the WSJ is ominous:

In addition to $2 trillion in assets Citigroup has on its balance sheet, it has another $1.23 trillion in entities that aren’t reflected there… Among the off-balance-sheet assets are $667 billion in mortgage-related securities.

So there’s many more toxic assets still to be owned up to (read Felix Salmon’s take). Meanwhile, the Economist points out the obvious:

One thing that we know will be fun is watching Mr Paulson defend the purchase of $100 billion of Citi’s junk, while simultaneously arguing that Detroit shouldn’t get a dime from TARP.

Update III: Shareholders like the deal – initially at least. Commentators from left and right think the US government got ripped off: Krugman:

A bailout was necessary — but this bailout is an outrage: a lousy deal for the taxpayers, no accountability for management, and just to make things perfect, quite possibly inadequate, so that Citi will be back for more. Amazing how much damage the lame ducks can do in the time remaining.

Arnold Kling:

The one sector that definitely needs to contract is the financial sector. Maintaining Citi as a zombie bank is not really constructive. I would feel better if it were carved up, with the viable pieces sold to other firms and the remainder wound down by government. In my view, getting the financial sector down to the right size ought to be done sooner, rather than later.

My questions: (i) How long before another bank wants the same kind of deal? (ii) Is there anything Paulson can now do to rescue his credibility? (iii) How long before the scale of Citi’s problems are fully understood?

Some answers/guesses: (i) Two weeks. (ii) No – he’s changed direction too many times. (iii) Between 2 and 5 years.

by David Steven | Nov 15, 2008 | Global system, London Summit

In our paper on Bretton Woods II (pdf), Alex and I provide rather a gloomy assessment of financial crisis – which we suggest is going to last longer than many think…

Given that we now face what Gordon Brown has described as “the first truly global financial crisis of the modern world”, our bet would be that it takes as long as a decade to bring it fully under control.

Let’s unpack the assumptions behind our pessimism. We start from the premise that, six months back, experts were overly optimistic about how far-reaching the meltdown would be. This is based, in part, on April’s Progressive Governance summit, where heads of state were (a) clearly freaked out; (b) fairly sure they grasped the problem, if not the solutions; (c) not acting as if they expected any further big surprises.

Consider, too, what the IMF’s Dominique Strauss Kahn was saying at the time. He was as worried by inflation, as he was by economic slowdown. Although he was forecasting a “rather important, serious slowdown in economic growth” – the expected pain wasn’t really that bad:

Something around 0.5 percent as a rate of growth for the United States in 2008 and a slight recovery during 2009-an average of 0.6 percent for 2009, which is both linked to the financial turmoil, of course, but also the business cycle.

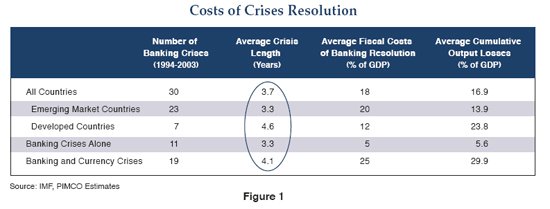

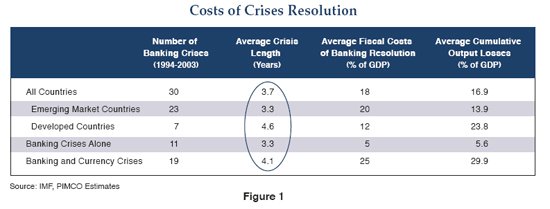

Next, we look at the lessons of earlier banking crises that, in developed countries, have tended to take four or five years to unravel, cost around 12% of GDP to resolve, and lead to a cumulative loss in output equal to almost a quarter of GDP. The figures are drawn from this useful chart prepared by PIMCO’s Michael Gomez:

Then add in what we know about the banking crisis that gripped Japan in the 1990s, which the IMF ascribes to “accelerated deregulation and deepening of capital markets without an appropriate adjustment in the regulatory framework”. Hiroshi Nakaso’s account is worth reading in full – seven years of crisis management and fire fighting as a senior manager at the Bank of Japan.

“When the bubble burst in the early 1990s, no one expected it was going to usher in such a prolonged period of weak growth in Japan,” he writes. Policy makers underestimated the seriousness of the problem, while banks lacked the ‘foresight and courage’ to confront their predicament head on.

At the time there was considerable schadenfreude in the West about Japan’s failure to get to grips with its crisis. It was eight years or so before its policy makers even found the levers that would begin to inch the crisis towards a solution. Are we right to assume that we’ll now do better? (more…)

by Alex Evans | Nov 13, 2008 | Climate and resource scarcity, Cooperation and coherence, Global system, London Summit

Ahead of this weekend’s G20 summit, David and I have published a short paper entitled A Bretton Woods II worthy of the name. Key points:

– The summit is unlikely to be able to live up to its billing. Leaders do not yet understand the nature of the problem well enough to be able to implement viable solutions. However, the problem is more fundamental than a simple lack of shared awareness.

– History suggests that leaders will only think the unthinkable on institutional reform once the challenge they face has really hit rock bottom. But history also suggests that we are wrong to think that the worst of the crisis is now past, given that many past banking crises have taken five years or more to unravel.

– Bretton Woods 1 looked across the whole international economic waterfront in 1944, while this weekend’s summit will be much more narrowly focused. Leaders will make a big mistake if they try and tackle finance in isolation, given the growing impact of resource scarcity, and that 2009 is supposed to see another ambitious global deal – on climate.

– We need to recalibrate what we expect from globalization through a serious debate about subsidiarity. Where has globalization gone too far, too fast? Where do we need more integration at a global level? These were exactly the questions that preoccupied Keynes in 1933, when he weighed the relative benefits of global versus local across a range of variables. We need a similar debate today as a precursor to serious international economic reform.

– Leaders need to extend their horizons in (at least) five directions: onto longer time scales; beyond financial regulation into wider resource scarcity challenges; into other international processes, especially climate; towards grand bargains with emerging powers; and beyond government, to non-governmental networks.

Full version after the jump, or better yet here’s the pdf.

(more…)

by Alex Evans | Nov 7, 2008 | Global system

Just after the Bank of England’s stunning 150 basis point cut yesterday, BBC business editor Robert Peston noticed an alarming signal of problems ahead. He wrote:

I’ve just had a call from an astonished individual who has several hundred million pounds that he puts on deposit in various banks. As of 10 minutes ago, a leading British bank was offering to pay him almost 7% interest for his cash. That was after the Bank of England’s policy rate had been slashed by 1.5 percentage points to 3% – an unprecedented reduction in the history of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee.

Why does it matter that this holder of squillions is still being offered almost 7%? Well, if he’s being paid almost 7%, what chance is there that small businesses will be able to borrow at less than 10, 12, 14% or more (with the actual rate depending on an assessment of their credit-worthiness)?

Peston’s conclusion: “the transmission mechanism from the Bank of England’s policy rate to the interest rates we pay has broken down“. This morning, the front of the FT confirms the problem:

All but two UK banks snubbed government calls to pass on Thursday’s dramatic interest rate cuts to new customers and more than 20 lenders withdrew deals that would have slashed borrowers’ monthly mortgage repayments … Lloyds TSB and Abbey were the only two lenders to say they would pass on the full rate cut in their standard variable rates.

What’s at stake here is potentially rather larger than simply the question of providing some much-needed relief for mortgage holders and small businesses, or the political issue of whether banks in receipt of taxpayer bailouts have a duty to pass on the rate cut.

No, the bigger question is about the degree and efficacy of state control over monetary policy – full stop. Here’s how it’s supposed to work in the words of the Bank of England:

When the Bank of England changes the official interest rate it is attempting to influence the overall level of expenditure in the economy. When the amount of money spent grows more quickly than the volume of output produced, inflation is the result. In this way, changes in interest rates are used to control inflation.

The Bank of England sets an interest rate at which it lends to financial institutions. This interest rate then affects the whole range of interest rates set by commercial banks, building societies and other institutions for their own savers and borrowers.

Well, that’s the theory, anyway. But what happens if it no longer works?

by Alex Evans | Nov 2, 2008 | Global system

Marcello Simonetta in Forbes agrees that current events have a certain familiarity to them – but he’s looking a lot further back than everyone else. Specifically, he’s been immersed in Raymond de Roover’s 1963 tome The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank (1397-1494)…

Now, as then, the coordination between different branches or departments continues to be a major issue confronting administrators in business as well as in governments. Choosing the right person as a manager is no less difficult than finding the right heir to the business or the reign.

After Cosimo’s death, his son, Piero, and his grandson, Lorenzo, had a much less steady hand on the branch managers and gradually lost their grip on the banking empire. Diminished economic power brought about troubles at home, where in 1478 the so-called Pazzi Conspiracy–an attempted coup organized by a rival banking family secretly helped by the Roman Catholic Church–brought Lorenzo to his knees.

By the time Cosimo’s grandson tried to recover control over Florence, the Medici Bank was near collapse, which led to many irregularities. One disgruntled citizen commented after a two-year bout of warfare: “Cosimo and Piero (grandfather and father), with half of the money you have spent on this war, would have gained much more than you have lost.”

This might remind us of other recent disastrous military and monetary enterprises. Then, as now, too much money badly accounted often damages the purpose for which it is spent. Lorenzo, desperately in need for monies, turned business into a matter of state and took money from his own relatives to defend himself and the city, and also diverted public funds for his own use.

The fear of being annihilated by foreign powers, combined with the lack of transparency, allowed the ruler of the Republic to turn it into an effective tyranny. With the declared purpose of defending Florentine freedom and its way of life, Lorenzo raised taxes for the war and embezzled banking funds with the result (does this sound familiar, anyone?) of creating a huge credit crunch.

The Medici Bank–as De Roover argued–had tenuous cash reserves that were usually well below 10% of total assets. Lack of liquidity was an issue for banking since its origins. Of course, in the Renaissance they dealt with thousands or millions of florins–billions were yet unthinkable. But would a bailout have been thinkable at the time? Lorenzo certainly bailed himself and his family out of a political and financial mess with public funds. He eventually gained for himself the superlative epithet of “The Magnificent” by obtaining foreign military support and by compromising his city’s liberty.

However, shortly after his death in 1492, his weak son Piero was thrown out of Florence. Perhaps that was an early instance of what we would now call kicking the debt problem onto the next generation.