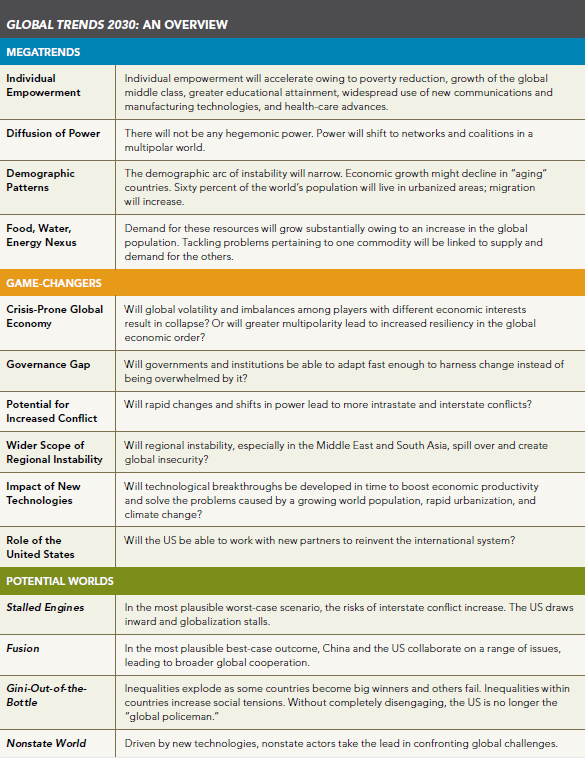

Here’s a snapshot of the defining features of the world in 2030, courtesy of the US National Intelligence Council’s excellent Global Trends 2030 report, the latest in a series of reports – published, in each case, shortly after US Presidential elections so as to be ready in the in-tray of the new National Security Adviser, whatever the political stripe of the incoming Administration.

Here’s a snapshot of the defining features of the world in 2030, courtesy of the US National Intelligence Council’s excellent Global Trends 2030 report, the latest in a series of reports – published, in each case, shortly after US Presidential elections so as to be ready in the in-tray of the new National Security Adviser, whatever the political stripe of the incoming Administration.

The report pulls no punches on the risks of rising inequality – indeed, one of its four headline scenarios is entitled ‘Gini out of the bottle’, and describes a world in which inequalities within countries lead to “increasing political and social tensions”, inequalities in China “increase and split the Party” with middle class expectations not met except among the “very ‘well-connected'”, and “more countries fail, fueled in part by the dearth of international cooperation on assistance and development”.

It’s also emphatic about the risks that come from the food, water and energy nexus. A new Human Resilience Index, commissioned by the NIC from Sandia National Laboratories and presented in the report, is based on a mixture of demographic and ecological indicators. This focus on scarcity issues leads to some interesting conclusions – e.g. Ethiopia is cited as the world’s 10th most fragile country on this basis, ahead of Pakistan, Niger or Chad (c.f. a report of mine on scarcity risks in Ethiopia from a few months back). Interestingly, the index also concludes that the world’s 15 most fragile places in 2030 are precisely the same ones as the index identifies in 2008, albeit in a different order.

Also interesting – NIC also worked with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory to identify natural disaster scenarios that could be so severe as to cause nations to collapse. They found four: staple crop catastrophes (which could be triggered, for example, by atmospheric aerosols following volcanic eruptions); tsunamis in selected regions (including Tokyo); erosion and depletion of soils; and solar geomagnetic storms.

And prospects for multilateral cooperation in all this? In essence, NIC concludes that the jury’s still out, and much will depend on whether the US and China can work together. On climate, the worst case scenario is that “global economic slowdown makes it impossible for the US, China and other major emitters to reach meaningful agreement … the result leaves UN sponsored climate negotiations in a state of collapse, with greenhouse gas emissions unchecked”. (I thought that was where we were already, but there we are.)

And the best case? Not that great, it turns out: “Cheaper and more plentiful natural gas makes emissions targets easier to achieve, but ‘two degree’ target would be unlikely to be met”. The silver lining? “As disparities between rich and poor countries decrease, rising powers may be more prepared to make sacrifices”. Which kind of leaves the question hanging, “…and will the US be prepared to make any sacrifices?”