What type of ethnic divisions and political circumstances are most likely to produce conflict?

There is no easy answer, but there are formulas that can provide a guide.

Joel D. Barkan, Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa, provides a good one in his chapter on East Africa in the new book On the Fault Line: Managing Tensions and Divisions within Societies. He argues that the presence or absence of severe social divisions and their varying ‘depth’ is a function of the interplay between three variables:

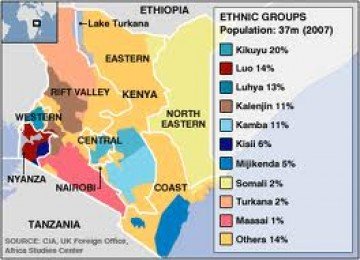

- The extent of ethnic, religious, or clan fractionalization and the relative size of competing groups

- Whether the country in question is marked by uneven levels of development and incorporation into the world economy that has privileged some groups over others

- The extent to which political leaders seek to mobilize populations on the basis of appeals to ethnic, religious, or clan identification and grievance

Where populations are divided into a small number of large identity groups, development is highly uneven (and is perceived as being highly favorable to some groups over others), and political leaders encourage the disadvantaged to feel aggrieved, politics becomes focused on a zero sum competition for state resources. Conversely, where populations are divided into a large number of small identity groups, the pattern of uneven development is less pronounced, and politicians do not stress identity politics, the probability that ethno-regional communities will conflict is low. Instead, policies and occupational or class interests are likely to matter more to political competition.

In Africa, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Nigeria fit into the first category. Tanzania the second. In the Middle East, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq fit the first category.

The problem for leaders in countries with difficult political geographies and a history of uneven development is that they cannot change the first two variables, at least not in the short-to-medium term. “It is thus the approach taken by a country’s political elites and their interaction with the two structural variables that accentuate or mitigate the fault lines that divide society [italics in source].”

Elections can easily exacerbate these divisions, as Kenya has shown a number of times in its history. “Politics … become a never-ending game of ethnic ‘musical chairs.’ In the run-up to each election, coalitions form and reform among the largest groups, but in the process divide their countries, often deeply, into what becomes a zero-sum game between rival ethnic coalitions.”

What can a country do in these circumstances?

Forming a compensatory system that mitigates against these factors requires some form of federalism that is tailored to the particular permutation of ethnicity and development. Breaking up the largest identity groups: appears to be the most effective way to both accommodate and navigate the existence of ethnic fault lines. However, to be financially viable and mitigate the impact of uneven development, federalism requires a system of equalization grants managed by the central government. This is because residents of poor areas are rarely able to raise sufficient revenue to finance their local and state governments.

Nigeria has avoided severe ethnic and religious conflict since its civil war in the late 1960s by adopting just such an approach.

Ethiopia is trying to mitigate conflict by decentralizing power directly to major identity groups, without any attempt to break them up. Time will tell whether this approach, which has worked well on other continents (in Canada, Belgium, India, and so on), can work in Africa.

Regionalism, which he does not discuss, can also mitigate identity conflict by making the state less relevant to individual groups. In places such as West Africa where many tiny fragile states exist side-by-side, only a regional approach is likely make a substantial difference given the weakness of state institutions.