Finally, some proper media coverage of the appalling budgetary nightmare in which the UK Foreign Office finds itself – the result less of actual budget reductions (though that problem is certainly in the post too), but of the pound’s decline against the US dollar. Alex Barker and Anna Fifield in the FT:

The problems at the Foreign Office were caused by a Treasury decision in late 2007 to stop shielding it from currency fluctuations a few months before sterling’s 30 per cent decline against the dollar. As a result the Foreign Office lost about £100m from its £830m core budget this financial year, in spite of attempts to hedge. The shortfall is expected to rise to £120m in 2010-11, close to 15 per cent of the core budget.

Most coverage has focused on what this means for counter-terrorism budgets in Pakistan (although wouldn’t you know, the Telegraph has found a bonuses angle to the story). But that’s just a microcosm of a much larger issue.

Reflect for a moment on the fact that the three defining events of the last decade – 9/11, the 2008 food and fuel price spike, and the credit crunch and ensuing global downturn – were all fundamentally about foreign policy.

More than that, they were about a collective failure by states to manage trans-boundary global risks, as David and I argued in our article on global resilience for World Politics Review last year. (By the way, we’ll be publishing a new Brookings Institution report on Confronting the Long Crisis of Globalisation next week, co-authored by us and CIC director Bruce Jones – this to coincide with the 40th anniversary meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, which takes ‘global redesign’ as its theme.)

True, the Foreign Office is not the lead department on terrorism, resource scarcity or international economics. It’s hardly as if FCO could have prevented 9/11, the resource spike or the credit crunch on its own. But that’s the whole point. No-one – no one government department, no one company, no one country – can manage these risks on their own. Which means better risk management is fundamentally about influence: persuading coalitions of states, international organisations and non-state actors to collaborate in pursuit of global resilience.

So one might think that a properly resourced (and, we would argue, reformed) Foreign Office would be recognised as central to the UK’s ability to work to manage global risks. Instead, the Treasury has left FCO to swing in the wind over a failure to hedge against currency fluctuations (something you might suppose would be the Treasury’s job in the first place) – and on top of this will look to cut the Foreign Office’s budget in the next Spending Round.

It’s not just the irony that every time FCO’s budget gets hammered, it’s because the rest of the government is having to clear up after the Treasury’s failures – whether in currency hedging, or having to bail out the banks (breaking the public sector bank in the process) because the Treasury screwed up financial regulation.

It’s that it shows such a truly awe-inspiring inability to learn from past mistakes. Never mind whether HMT is shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted on the credit crunch. By taking the knife to the Foreign Office, it seems hellbent on letting all the other horses out too. If we want to shift from constant fire-fighting against global risks towards actual prevention – which, bean counters note, also happens to be much cheaper – then we should be scaling up FCO’s budget dramatically, and turning it into an influence projection platform fit for the 21st century.

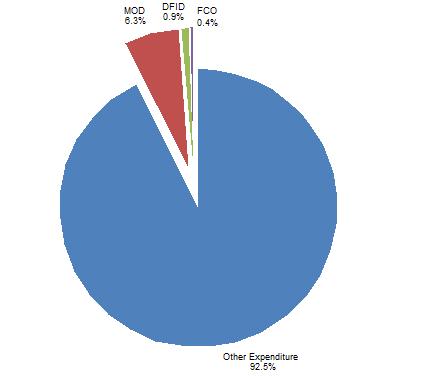

It’s not even as if it’ll be that expensive, for heaven’s sake. The FCO’s budget is peanuts in the larger scheme of things (see chart below, which shows UK spending on the three international departments as a proportion of total government expenditure). You could eliminate the Foreign Office altogether, and the dent you’d make in the deficit wouldn’t be more than a rounding error.

(P.S. It’s worth noting that – contrary to what you might suppose – the arguments above apply to DFID as well as FCO. True, DFID’s programme budget is rising steadily upwards towards 0.7% of GNI. But its admin budget – including staff – will also be under severe pressure in the next Spending Round.

It’s already had to lose one in six staff since the Efficiency Review in 2005. If you go to their offices in Palace Street, you find that they’ve let out their entire top floor to other tenants. So if, as we’ve long argued here, effective development work depends on people as much as money, then DFID too needs to be properly resources in headcount terms.)