by Mark Weston | May 13, 2009 | Africa, Climate and resource scarcity, Global Dashboard

Further to recent Global Dashboard posts on the attempts by rich countries to buy up African agricultural land (here and here for example), an article I wrote for this month’s EMEA Finance magazine explores the subject in more detail.

The main problem with the deals, I argue, is the difficulty of valuing them in a rapidly-changing global food market. For African countries which lack expertise in such matters, there is a huge danger that they will be ripped off. But the risks are also great for investor countries, as the recent collapse of South Korea’s bid to buy up land in Madagascar has shown. For the deals to work, they will need to be radically different to those made so far – more transparent, properly regulated, beneficial to local people and shorter. More important still, however, is for Africa to realise its own potential for food production, which would in the long-term negate the need for these deals.

For the full article, see after the jump.

(more…)

by Mark Weston | May 1, 2009 | Africa, Climate and resource scarcity

Just a quickie on the Madagascar coup from a Royal Africa Society talk I attended on Tuesday. According to Volatiana Rahaga, who is president of the Association of Malagasy Residents in the UK (all 100 of them), news of South Korea’s deal to buy up a large chunk of Madagascar’s arable land may never have filtered through to the public had it not been for a pesky FT journalist.

The FT’s Javier Blas reported on the deal when the negotiations had almost finished. Until then, nobody in Madagascar knew anything about it. When members of Ms Rahaga’s group read Blas’s article, they e-mailed the news to colleagues in France (which has a much larger Malagasy diaspora). The latter then told their friends and relatives back home about it, and the brown stuff promptly hit the fan. At first, the recently-ousted president, Marc Ravalomanana, denied that any such deal was going through; when he was eventually forced to tell the truth, it was too late. Everyone assumed the worst – that he and his cronies were making millions from the plan at the expense of the Malagasy public, who not only would not be compensated but would face an increased risk of food shortages once they surrendered all that farmland.

As an environmental consultant based in Antananarivo told me, this failure to communicate the deal doomed it, and public anger about the sell-off was partly responsible for the coup that deposed Ravalomanana this spring. In today’s wired up world, it seems, even authoritarian African governments can no longer count on a monopoly on information.

by Mark Weston | Apr 15, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity

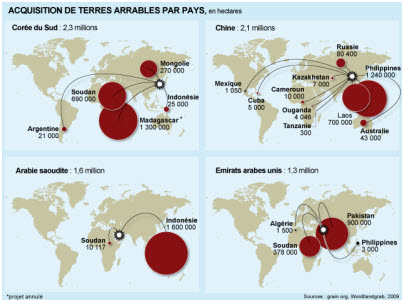

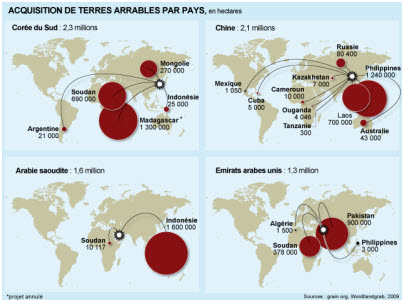

Further to Alex’s recent posts (here, here and here) on wealthy countries’ purchases of arable land in the developing world, here’s a map from Le Monde showing the main buyers of land, their primary targets, and the amount of land in hectares they are buying up. The map includes both done deals and deals that are still being negotiated. Note the massive sell-offs by the Philippines, Indonesia, Pakistan and Laos to China, Saudi and the United Arab Emirates. Excuse the French.

by Alex Evans | Mar 24, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Conflict and security

Back in November last year, I blogged on the land lease deal agreed between Daewoo, the South Korean company, and the government of Madagascar, under which the former would lease fully one half of Madagascar’s arable land for a hundred years. Soon afterwards, the news emerged that Madagascar would receive no payment at all for the lease – the only upside would instead be the prospect of some job creation.

Since then, of course, Madagascar’s government has fallen in a coup d’etat. But what I hadn’t spotted until a US Department of Agriculture official mentioned it to me last week is the fact that the land deal was front and centre in what made the coup happen. Here’s Tom Burgis in the FT on Saturday:

“Everything was a monopoly with [President] Ravalomanana,” says Naina, a 41-year-old wood chopper in one of the capital’s poorest neighbourhoods. “The country could not develop.”

The bombshell that turned the discontent into outright anger and so brought an end to Mr Ravalomanana’s rule was news of a deal between the government and Daewoo Logistics. This envisioned leasing vast tracts of Madagascar’s arable land to the South Korean conglomerate to grow crops that would be exported from a country where aid agencies were battling rural starvation. “It was the news that said Daewoo expected to pay nothing for the land that accelerated the trouble,” says one well-connected Malagasy banker who asks not to be named.

At a stroke, alienated members of the Malagasy elite found the banner to which they could rally an urban poor already struggling to cope with rice prices driven higher by the global commodity boom. They also found a figurehead in Andry Rajoelina, a 34-year-old former DJ who had married into Malagasy aristocracy and built the capital’s foremost billboard advertising operation …

Thousands took to the streets, whipped up by the Daewoo deal as the symbol of all that was ill. Protests turned to looting. Scores died as buildings burned. Then, in early February, Mr Rajoelina lead a boiling crowd from the main square to the gates of the state palace. Amid the confusion, the presidential guard opened fire.

By now we’re all well used to the idea that oil, diamonds, coltan, poppies and other high-value commodities can lead to a ‘resource curse’ in fragile states – for instance when the resource endowment ‘crowds out’ other sectors of the economy (e.g. through exchange rate rises), or props up poor governance. Hitherto, though, only a few food crops – like coffee and cocoa – have been on the list of potential resource curse drivers.

I found myself wondering a couple of weeks ago whether the prospect of long term food price inflation and proliferating security of supply concerns in places like China, South Korea and a raft of Gulf countries, might lead to growth in the pool of potential resource curse drivers. Having seen the first government fall as the result of a landgrab deal, I think we now know the answer…