by Molly Elgin-Cossart | Apr 14, 2014 | Cooperation and coherence, Economics and development, Global system, North America

When finance ministers and central bankers from the G20 major economies met last week in Washington, they rapped the United States on the knuckles for its failure to ratify reforms of the International Monetary Fund. The reforms, which leaders from around the globe agreed in 2010 but which require U.S. Congressional ratification to be implemented, would increase the voice of emerging market economies on the IMF’s board and strengthen its general account (what the IMF calls “quotas”). In the G20 final communique, the global financial chiefs expressed how “deeply disappointed” they were, and fired off a stern warning, giving the U.S. until the end of the year before they request the IMF to proceed on reform (without the United States, to insert the subtext). Given that the U.S. was instrumental in founding the IMF and has always been its largest shareholder and exercised a veto over major institutional changes, the warning is serious stuff. Whether or not the IMF can actually do anything without the buy-in of its largest shareholder remains in question, but certainly the rest of the world is growing impatient with the extended delay.

In a recent analysis, I point out that the delay is undue. The IMF has traditionally enjoyed support from Democrats and Republicans, and the current proposal for reforms builds upon a process that began under the George W. Bush administration. The IMF helps to maintain global financial stability and prevent and mitigate economic crises, something both parties can get behind. The reforms strengthen the IMF’s core capabilities and improve its governance, equipping the IMF to better prevent and manage economic crises of the twenty-first century and creating a platform for constructive relations with emerging market economies such as India, Brazil and China.

And despite some claims to the contrary, the reforms do not increase U.S. financial commitments, because the new U.S. contribution to the IMF general fund would be offset by an equal reduction in its commitment to another IMF fund (the New Arrangements to Borrow). The Congressional Budget Office, Congress’ official budget scorekeeper, estimates the technical cost of implementing the quota reforms at $239 million – but also estimates that shifting the funds away from the NAB would save $693 million over the same time frame. So the reforms don’t increase US financial commitments, and the US might actually recoup money on account maintenance costs. A pretty good deal.

The case for the reforms seems obvious, so why the delay? The toxic political environment in Washington is the primary culprit. The Obama administration has not made the case for reforms as clear and compelling as it could and should, and delayed proposing them, while Congress is loath to give the Administration any kind of victory. And with the rise of tea party influence in the Republican party and an increasingly isolationist American public, Congressional blockers may actually reap political rewards. In return for ratifying IMF reforms, some Republicans are demanding a delay in the Obama administration’s proposed rules to limit political activities of non-profits. (If that seems like a a non sequitur, that’s because it is. Such is political deal-making in today’s Washington.)

All of this is bad news for the U.S., and bad news for the world. The fact is that for now and the foreseeable future, the U.S. is still the world’s preeminent power. And that power must be exercised with commensurate responsibility. As the G20 warning made clear, the rest of the world will not wait indefinitely. They are already eying a plan B if the U.S. does not ratify the IMF reforms. Whether they act without the U.S. remains to be seen, but everyone loses if the U.S. does not step up to lead the modernization of an international system that emphasizes cooperation over competition. The IMF is an early but important step in a revitalized, rules-based global order that can manage the challenges of the twenty-first century.

by David Steven | Mar 19, 2014 | Economics and development, North America, UK

The IMF has attracted plenty of favourable attention from unfamiliar places with two ‘staff papers’ (we’re enjoined to consider them as the personal opinions of the authors, not the IMF itself, an injunction that we all merrily ignore). The first argues that inequality reduces growth, while redistribution is an effective tool for reducing it; the second explains how governments should use taxes and public expenditure to achieve this goal.

Inequality campaigners are over-the-moon to have the IMF on their side. Oxfam International hails the IMF for “mashing myths and debunking dogma in economic policy,” while the Oxfam inequality guru, Nick Galasso, is fulsome in his praise of an “ideological sea change” at the Fund (“if If it sounds like I have a crush on the IMF’s Managing Director, Christian Lagarde…”).

But what tools does the IMF think we should use to shrink inequality? Oxfam’s tweet leads to a Reuters article covering a speech by IMF deputy managing director, David Lipton. The speech is definitely worth reading in full – it’s a digestible summary of emerging IMF thinking, while the table on page 43 of the IMF report provides an overview of its suite of policy prescriptions.

Key recommendations for developed countries include substituting means-tested benefits for universal ones; raising the retirement age and making the rich work longer than the poor; charging more for university education in order to spend more on schools; and making income tax more progressive, while eliminating tax breaks.

Many of these are good policies, but let’s not pretend they’re all politically palatable. Take the last one as an example. In the United States, President Obama and the Republicans are locked into fruitless combat on eliminating a few of the most egregious pro-rich tax breaks. A recent revenue-neutral tax reform plan from a Republican has provoked a blizzard of protest from Wall Street and has been roundly condemned by his colleagues.

But the IMF is not interested in these small-bore controversies, it has the big one in its sights: the 37 million Americans who benefit to the tune of $70bn or so from tax relief on their mortgages. And that’s a political live wire. I’d speculate that any presidential candidate – Republican or Democrat – who ran for 2016 on a “tax the homeowners” platform would have as much chance of winning the nomination as I do.

This is not just an American problem. Look at the IMF’s core policy prescription for the United Kingdom – one good enough that it makes it into Lipton’s speech as well as into the report. The UK should move to a flat rate of VAT on all goods and services, Lipton argues, and use the money to increase benefits.

That would mean imposing a 20% tax on food (raising £16bn or so), and on rent and house construction (another £13bn), while increasing tax on household electricity and gas from 5% to 20% (£5bn). Tax would also go up on books, children’s clothing, tampons, condoms, stamps, charities like Oxfam, and… funerals. Yep – the IMF is proposing a burial tax.

All in all, this would give George Osborne £60bn to play with (table 4), more if he axes universal benefits in favour of greater means-testing (goodbye child benefit, winter fuel allowance etc). This would be enough to double benefits for working-age low earners and the unemployed (table 8.2).

Good news for inequality, maybe, but an act of political insanity. In the UK, we once had a manifesto that was derided as ‘the longest suicide note in history’. Flat rate VAT (for all its merits) would be the shortest. VAT on food? On books? On coffins? Just look at the disaster that befell the British government when it tried to tax Cornish pasties to see how badly this would go wrong.

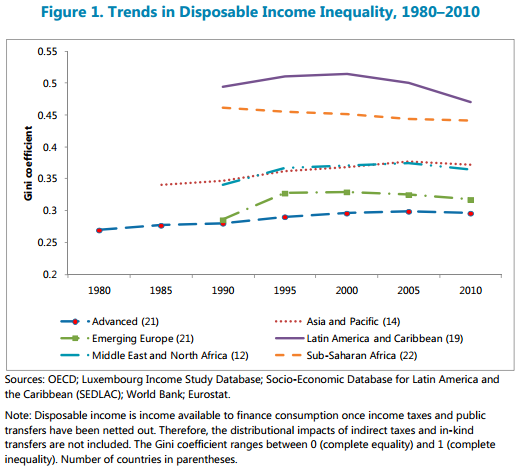

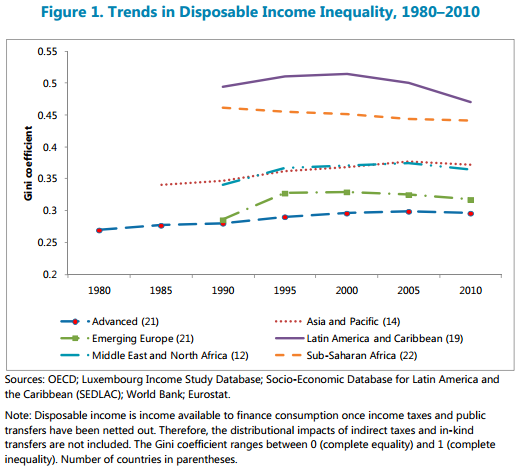

There are equally obvious political bear traps when you look at the problem from the point of view of low and middle income countries. And the task ahead of them is daunting, given that inequality levels are higher in Asia and the Middle East than in the West, and much higher again in Africa and Latin America. A European minister told me that he was hoping for a post-2015 goal that would inspire the whole world to be as equal as his country by 2030. I shudder to think of the collective apoplexy this prospect would cause in the G77.

No-one is pretending that IMF-branded policies represent the final word on inequality. Oxfam issued a media brief this week, which proposes the UK tackles inequality by cracking down on tax dodgers, implementing a Tobin tax and a tax on land, and increasing the minimum wage.

But what the Fund’s excellent report does is underline the importance of going from high-level aspirations to detailed scrutiny of the policies we want governments to implement to bring inequality down. Only then can we understand how today’s high level debate on inequality will play out in the bruising world of retail politics. It would be good to see Oxfam’s proposals costed and their likely impact on inequality audited, so we can see what they’ll deliver and who’d foot the bill. Without that the politics remain hard to read.

A greater focus on policies and implementation, and the politics of both, is especially important for those arguing that we should stop being “belligerent” about the “unrealistic goal” of ending sub-$1.25 a day poverty and instead build a post-2015 agenda on the the more sustainable political foundations that inequality offers.

Sure, we have an ‘emerging consensus’ that something needs to be done to bring inequality down. But will that consensus hold when publics around the world, and assorted lobbyists, get a better sense of what that something looks like?

by Alex Evans | Oct 19, 2012 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Influence and networks

The FT’s Gillian Tett reports today on a conference presentation given by historical sociologist Dennis Smith, who’s been working on the question of how humiliation operates at the cultural / collective psychological level – and what this means for the Eurozone.

The whole article‘s worth reading, but here are a couple of highlights. First, on how humiliation works:

Psychologists believe the process of “humiliation” has specific attributes, when it arises in people. Unlike shame, humiliation is not a phenomenon which is internally driven, that is, something that a person feels when they transgress a moral norm. Instead, the hallmark of humiliation is that it is done by somebody to someone else.

Typically, it occurs in three steps: first there is a loss of autonomy, or control; then there is a demotion of status; and last, a partial or complete exclusion from the group. This three-step process usually triggers short-term coping mechanisms, such as flight, rebellion or disassociation. There are longer-term responses also, most notably “acceptance” – via “escape” or “conciliation”, to use the jargon – or “challenge” – via “revenge” and “resistance”. Or, more usually, individuals react with a blend of those responses.

So what does that mean for European politics? Well, Tett continues, the Eurozone’s periphery countries have indeed experienced “a loss of control, a demotion in relative status and exclusion from decision making processes (if not the actual euro, or not yet)” – and it’s interesting to observe how different European countries have used different coping strategies:

National stereotypes are, of course controversial and dangerous. But Prof Smith believes, for example, that Ireland already has extensive cultural coping mechanisms to deal with humiliation, having lived with British dominance in decades past. This underdog habit was briefly interrupted by the credit boom, but too briefly to let the Irish forget those habits. Thus they have responded to the latest humiliation with escape (ie emigration), pragmatic conciliation (reform) and defiant compliance (laced with humour).“This tactic parades the supposedly demeaning identity as a kind of banner, with amusement or contempt, showing that carrying this label is quite bearable,” says Prof Smith. For example, he says, Irish fans about to fly off to the European football championship in June 2012 displayed an Irish flag with the words: “Angela Merkel Thinks We’re At Work”.

However, Greece has historically been marked by a high level of national pride. “During 25 years of prosperity, many Greek citizens had been rescued by the expansion of the public sector?.?.?.?they had buried the painful past in forgetfulness and become used to the more comfortable present (now the recent past),” Prof Smith argues. Thus, the current humiliation, and squeeze on the public sector, has been a profound shock. Instead of pragmatic conciliation, “a desire for revenge is a much more prominent response than in Ireland”, he says, noting that “politicians are physically attacked in the streets. Major public buildings are set on fire. German politicians are caricatured as Nazis in the press?.?.?.?the radical right and the radical left are both resurgent.”

Prof Smith’s research has not attempted to place Spain on the coach. But I suspect the nation is nearer to Greece in its instincts than Ireland; humiliation is not something Spain has had much experience of “coping” with in the past. Whether the Spanish agree with this assessment or not, the key issue is this: if Angela Merkel or the other strong eurozone leaders want to forge a workable solution to the crisis, they need to start thinking harder about that “H” word. Otherwise, the national psychologies could yet turn more pathogical.

by David Steven | May 15, 2011 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America

Extraordinary news here in New York where the IMF’s Dominique Strauss-Kahn was this afternoon hauled out of the first class cabin of an Air France plane at JFK airport to be arrested for – allegedly – sexually assaulting the chambermaid in his room at the Sofitel Hotel.

According to the New York Times, Strauss-Kahn fled to the airport after the attack, leaving his mobile phone in his room, but was apprehended just 10 minutes before the plane was due to depart.

Strauss-Kahn, who had been expected to run for French President, was embroiled in a sex scandal back in 2008, when he slept with an IMF employee at Davos, and was then accused of ushering her into a new job outside the Fund. Unlike the World Bank’s Paul Wolfowitz, who was forced out for giving preferential treatment to his partner, Strauss-Kahn kept his job.

Ironically, it was only on Friday that the Guardian ran an article by French journalist, Melissa Bounoua, lauding the open-mindedness of the French voter, who she claimed would happily have Strauss-Kahn as President, even if he were a serial shagger for whom consent wasn’t that big a deal.

Is Dominique Strauss-Kahn, current head of the International Monetary Fund, a “queutard” – literally, a man who makes extensive use of his intimate parts?[…] Strauss-Kahn (widely known as DSK) had an affair with Piroska Nagy, a Hungarian economist, while working at the IMF in 2008…

That wasn’t the only scandal. There was a fuss last year when a young French author, Tristane Banon, described her encounter with him. She explained that she had interviewed him for a book about public figures and their missteps, and claimed she had to fight him off physically…

“Personally, I doubt this side of DSK’s life would have any influence on how he would run the country,” Ms Bounoua claims in an article that makes all the usual excuses for the sexual proclivities of the powerful and is hailed, rather breathlessly, by the Guardian’s Jessica Reed as giving readers “sex, power, politics AND… a new French word: queutard.”

One wonders how Ms Bounoua and the Guardian will react to this new ‘fuss’…

Update: It’s worth remembering that ugly, if unproven, rumours have swirled round Strauss-Kahn for many years. Here’s Felix Salmon – now with Reuters, and one of the best financial journalists around – discussing the Frenchman’s ‘lower half problem’ in 2007 before he took over at the IMF.

Salmon quoted French journalist Chris Masse’s account of a previous Strauss-Kahn ‘fuss’:

A cable TV show (“93 Faubourg Saint Honoré”, on Paris Premiere, hosted by Thierry Ardisson) invited a young (and unknown to me) French actress. I don’t remember her name. She said that she had a bad encounter with Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Here’s what happened. She was asked to come in a little apartment he had in Paris, and then the next thing, Strauss-Kahn jumped on her and tried to undress her and more. She yelled, and told him that that was a rape, but the word “rape” (“viol” in French) didn’t seem to perturb him. She said that he was like “a gorille en rut” (a gorilla in rut).

by Mark Weston | Dec 20, 2010 | Africa, Economics and development

As the IMF agrees to grant Guinea-Bissau $700 million of debt relief, the European Union, the country’s main donor, threatens to withhold $150 million of aid.

Guinea-Bissau’s leaders will at least be pleased it’s not the other way round.