by David Steven | Nov 9, 2011 | Economics and development, Global Dashboard

It’s interesting to look back a few years – to when the world was worried that food was too cheap, not too expensive.

In 2004, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization looked back on a long bear market for food: forty years in which real prices of agricultural commodities had fallen 2% per year, or 50% between 1961 and 2002.

Innovation had driven up yields and productivity; growing numbers of suppliers had flooded onto global markets; and subsidies were keeping production levels artificially high. It was good news for consumers, but bad news for farmers and for poorer countries reliant on food exports, where low prices had “battered income, investment and employment.”

In his introduction to the State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2004, the FAO’s director general, Jacques Diouf, delivered a homily on the chronic oversupply of food. Prices in the mid-1990s were lower than at any time since the Great Depression, he complained, eroding the viability of rural communities and fuelling migration to cities.

There were winners and losers of course, but more of the latter than the former:

The main bene?ciaries of lower food prices have been consumers in developed countries and in urban areas of developing countries.

However, for the vast majority of the world’s poor and hungry people who live in rural areas of developing countries and depend on agriculture, losses in income and employment caused by declines in the prices of the products they market generally outweigh the bene?ts of lower food prices when commodity prices fall.

FAO wanted the problem of oversupply fixed. It called for rich countries to cut subsidies and take land out of production. Poor countries needed to stimulate demand for food, it said, and equip their farmers to export cash crops – preferably processed ones – to the West.

The next State of Agricultural Commodity Markets came out in 2006, by which time the FAO could see that times were a-changing. In real terms, food prices had bottomed out in May 2002, and had jumped 34% by the end of 2005. Good news? Well, no. (more…)

by David Steven | Nov 4, 2011 | Economics and development, Global Dashboard

The good news: poverty is in retreat. The bad news: hunger isn’t. That’s the headline finding for the first Millennium Development Goal , which aims to halve the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day and the proportion of people living in hunger between 1990 and 2015.

Great strides have been made on poverty, as I explained in a recent post, with the proportion of the poor projected to fall to 14.4% of the population of developing countries, from 41.7% in 1990. But what about hunger?

According to the UN’s 2011 assessment of the MDGs, the news is not good. In 1990, 828m people were hungry or 20% of the population of developing countries. Progress has been very slow since then:

The proportion of people in the developing world who went hungry in 2005-2007 remained stable at 16 percent [837m people], despite significant reductions in extreme poverty. Based on this trend, and in light of the economic crisis and rising food prices, it will be difficult to meet the hunger-reduction target in many regions of the developing world.

But hang on a minute. Why is the UN trotting out data for 2005-2007? That’s before the global food crisis, which hit at the same time as the financial crisis and has been just as slow to go away.

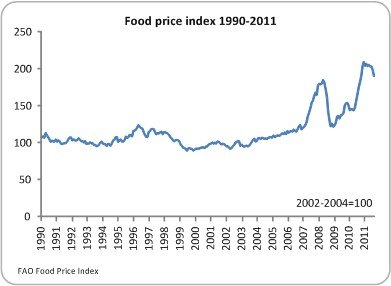

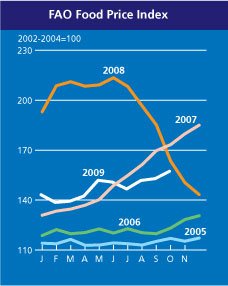

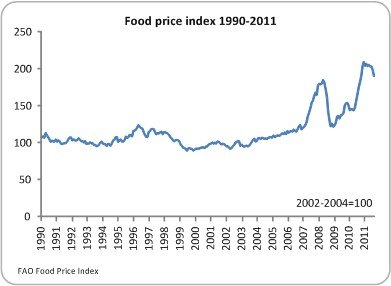

Food prices hit rock bottom in 1999, but then rose quickly with vicious increases in 2007 and 2008 (20% and 18%) and 2010 and 2011 (17% and 28%) as illustrated in the chart below. Yet we’re still relying on data from five years ago to estimate hunger.

The UN reported ‘dire’ news of a spike in its 2009 and 2010 MDG reports, with an estimate of more than 1 billion people hungry by 2009. But then it backed off in 2011, simply reporting the old data (which, oddly and without explanation, had been revised up slightly for all years, including 1990).

What gives? The problem is that our data on hunger are extremely patchy and rely on assumptions so heroic that I am left wondering if we are currently able to say anything useful about global hunger at all. (more…)

by Alex Evans | Dec 13, 2009 | Articles and Publications, Reports

World Food Programme report on the state of the science on what climate change means for hunger, plus policy recommendations. Authored by IPCC Impacts Chair Martin Parry with Mark Rosengrant, Tim Wheeler and Global Dashboard’s Alex Evans (December 2009)

Download Report

by Alex Evans | Dec 9, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development

The World Food Programme has just published a new report (pdf; also Reuters coverage here) on how climate change will affect hunger, which both summarises the state of scientific knowledge on the issue and sets out a policy agenda to tackle it. Key messages:

– By 2050, the number of people at risk of hunger because of climate change will be 10 to 20 per cent higher than it would have been without climate change.

– The number of malnourished children is expected to increase by 24 million – 21 per cent higher than without climate change.

– Sub-Saharan Africa will be worst affected, with the semi-arid regions either side of the equator hit hardest of all.

– But here’s the good news: if we get the policies right – on mitigation and on adaptation – the increase in the number of hungry people by 2050 could be limited to just 5% (which would actually be a substantial reduction in proportionate terms, given that population is projected to rise by 50% over the same period).

The lead author for the report was Martin Parry, the Chair of IPCC Working Group 2 (the part of the Panel that looks at impacts). I was one of three other authors, and wrote the part of the report covering policy responses.

by Alex Evans | Nov 11, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global Dashboard

I’ve said before that the easing of oil and food prices that followed the credit crunch and the global downturn gave policymakers a window of opportunity to take preventive action on scarcity issues. Now, alas, I think that window is starting to close – without their having done much about it.

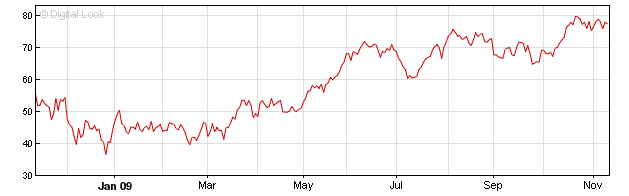

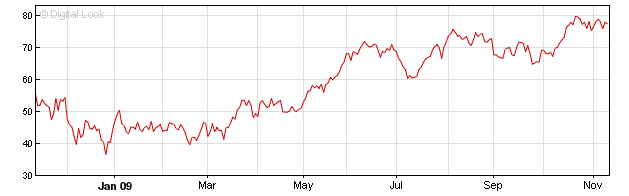

To see why, first take a look at what the oil price has been doing over the last year (Brent crude futures, $/barrel; h/t BBC):

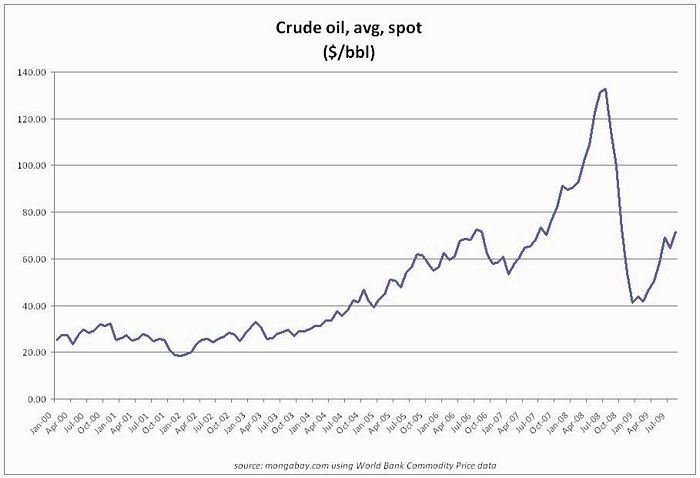

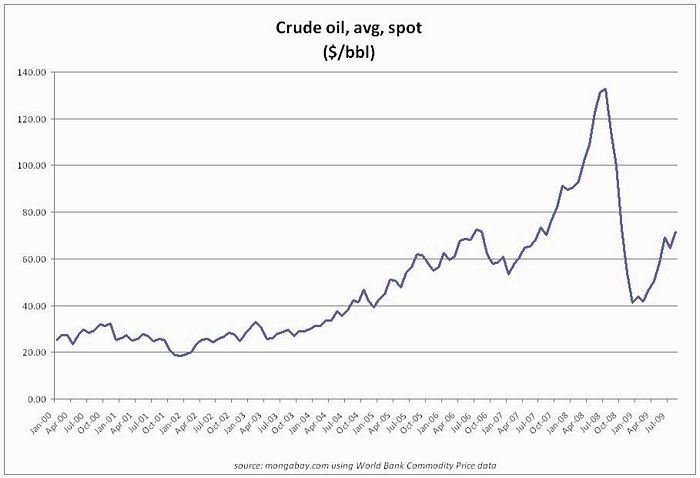

Then, put that against the longer term background of what’s been happening since 2000 (slightly older data here, via Mongabay, but usefully puts the BBC graph above in context):

As the second graph shows, today’s level of just under $80 per barrel already brings us back to where we were in around July 2007 – and that’s during a still shaky recovery from what’s generally agreed to have been the worst global recession since the early 1930s.

This is a striking rebound in such weak economic conditions – and calls to mind the consistent warnings from the IEA over the past 18 months that the collapse in investment in new supply during the financial crisis and subsequent downturn has set the stage for a new oil price crunch as soon as recovery gets underway (not to mention the fact that IEA’s chief economist thinks we’re looking at peak oil as soon as 2020).

With the oil price headed upwards, food prices can be expected to follow – because higher oil prices make biofuels more attractive, and raise the prices of on-farm energy use, fertilisers, transportation, distribution and various other elements of our energy-intensive food supply chains.

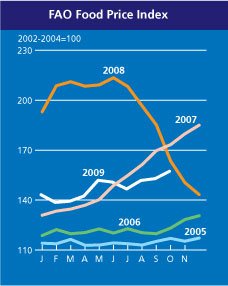

Sure enough, if we take a look at the latest FAO food price index, we find that it too has been quietly heading upwards over the last few months – and is now likewise back at where it was in July 2007. At that point, of course, the food spike was already well underway, with the tortilla riots in Mexico City that served as a wake-up call for many policymakers having come almost six months earlier.

On top of this, remember the really key point that the fall in food prices that took place during the global downturn gave minimal respite to the world’s poorest people – precisely because even as prices fell, they were also getting hammered themselves by the downturn.

The starkest indication of that is in the global total of undernourished people (shown here in a graph from the FT); when you realise that we haven’t just lost the progress of the last few years, but are in far worse shape that at any time since the last 60s, you start to see just what a catastrophe the combination of food / fuel price spike followed by global downturn has been for development:

As I’ve argued in numerous previous posts, we were never out of the woods on the food / fuel pincer movement; it was the collapse in prices following the credit crunch that was the blip, not the price spike that preceded it. And what’s most frustrating now is the extent to which policymakers have frittered away the chance we had to get onto a more secure footing.

(more…)