by Alex Evans | May 8, 2012 | Climate and resource scarcity, Europe and Central Asia

So near, and yet so far – as so often in EU climate policy. Back in December of last year, at the Durban climate summit, it looked as though the EU was finally getting on the front foot and managing to set the agenda for once on international climate policy.

Where the 2009 Copenhagen climate summit had seen the EU and its partners badly outflanked by a low ambition consensus of the US and the BASIC countries (leading to a voluntary pledge-and-review approach rather than the binding targets-and-timetables approach that the EU wanted), it appeared at the 2011 Durban summit that a new dynamic might be emerging – based on a partnership between the EU and low income countries who were not only increasingly focusing on global mitigation scenarios, but also increasingly prepared to break ranks with the G77 and speak out about the need for emerging economies to do more to reduce their own emissions.

The surprising spectacle of the EU managing to gets its act together will have made many US and emerging economy policymakers sit up and take notice. But all of them will also have been wondering whether the EU and its partners would manage to build on this initial success and turn it in to an inflection point on the global climate agenda, with the new alliance not only maintaining political momentum, but also converting it into design principles for future climate policy.

Alas, the signs now emerging are not good if this Reuters piece today is to be believed:

The European Union recommitted to providing 7.2 billion euros ($9.4 billion) for the Green Climate Fund over 2010-12, according to draft conclusions seen by Reuters ahead of a meeting of EU finance ministers next week. But after that, how much cash will flow is unclear as the text, drafted against the backdrop of acute economic crisis in the euro zone, states the need to “scale up climate finance from 2013 to 2020”, but does not specify how.

The article goes on to detail that EU ministers are arguing over how much of the money should come from public and how much from private sources – needless to say, many ministers would find it a lot easier to exhort the private sector to do more than to do pony up the cash themselves.

Although the article doesn’t name names on which countries are causing the problems, it’s a fair bet that Poland figures prominently among them, especially given that Poland vetoed plans for the EU to adopt a 30% (rather than merely 20%) emissions reduction target by 2020. In the background, there’s the further problem that Italy and Spain – two countries who in the past tended to side with calls for more ambitious action – are likely to fall away as their economies implode.

Although the Green Climate Fund is far from being the biggest issue on the climate negotiating table, it matters a lot to many low income countries. If the EU looks like it can’t be trusted to stick with them on the issues they really mind about most, then it’s hard to see an EU-low income country alliance setting the pace on the larger global climate agenda over the next couple of years – and we can look forward to lots of crowing from emerging economies made gleeful by the opportunity to argue that this is what happens when G77 solidarity is allowed to fracture.

by David Steven | Dec 9, 2011 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, UK

What a day. Five observations:

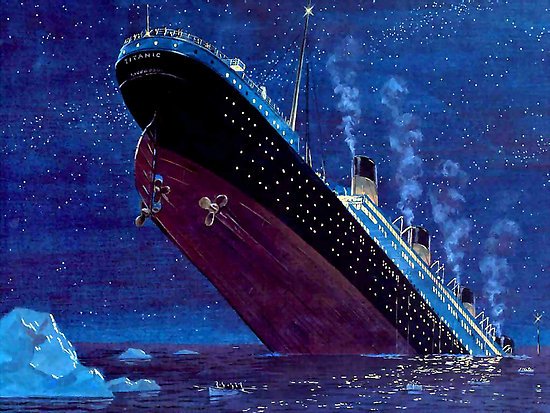

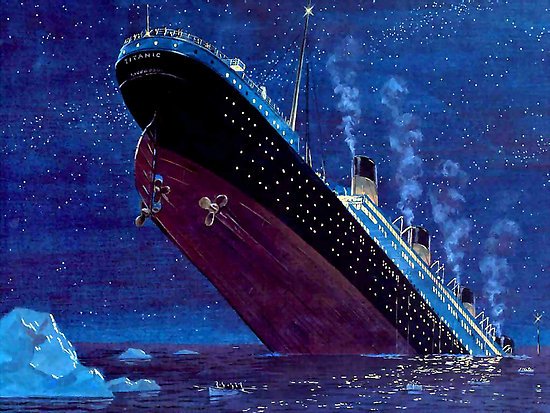

- My initial reaction this morning: On a sinking Titanic, the UK is lobbying to avoid further damage to the iceberg. If David Cameron was motivated mostly by his wish to suck up to the City (and to his backbenchers), then he deserves all that fate can throw at him. He has transformed eventual British exit from the EU from Eurosceptic fantasy to the new conventional wisdom in just 12 hours. Quite a feat.

- But maybe… his government has decided that the euro is now doomed and has made a rational decision to swim as far from the vortex as possible. Many believe that a disorderly break up of the single currency has become more likely than not. That would probably cost the UK 10% of GDP and make British default a near certainty. But if that’s what’s going to happen, then we better knuckle down to being as resilient to the shock as possible.

- The British veto makes euro failure more, not less, likely. In theory, agreement between a core group is easier than having all 27 countries in the room, but the legal complications of conjuring a new set of institutions from thin air are daunting. Also, expect the core to shrink as the summit’s aspirations are chewed up by domestic politics. Each defection will provide a potential trigger for wider breakdown – probably when a group of the strong decide all hope is lost, and make a collective rush to the lifeboats. By being the first to desert the ship, Cameron has made it much easier for other European leaders to follow.

- Contingency planning must now go much deeper. Behind the scenes, governments are playing out failure scenarios, and most big businesses have some kind of post-euro plan in place. Much of the thinking is still pretty rudimentary, however. The eurozone countries can’t risk letting markets see them flinch and have to put a brave face on their prospects, but the UK no longer needs to have such scruples. What exactly would we do if the euro goes down? What would be thrown overboard? What, and who, would be saved? How can the government organise effective collective action as the catastrophe hits?

- Nick Clegg is dead, politically. That was already true, but I can’t imagine even Miriam González Durántez now plans to support her husband at the next election. Paradoxically, accepting his terminal status could give Clegg new freedom of action. Instead of continuing to play the role of coalition gimp, he should offer leadership to those keen to explore what comes after the storm. Politicians with proper jobs – Cameron, Osborne, even Cable – are going to be overwhelmed by events throughout this parliament, even in the best case where Europe struggles back onto its feet. Clegg, though, has an opportunity to focus energy on the longer term. He’ll still lead the Lib Dems to electoral Armageddon, but catalysing a vision for renewal might make posterity a little kinder to the poor man.

by Mark Weston | Dec 20, 2010 | Africa, Economics and development

As the IMF agrees to grant Guinea-Bissau $700 million of debt relief, the European Union, the country’s main donor, threatens to withhold $150 million of aid.

Guinea-Bissau’s leaders will at least be pleased it’s not the other way round.

by Alistair Burnett | Aug 5, 2010 | Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia

Two years ago, Georgian forces shelled the capital of the breakaway region of South Ossetia hitting the base of Russian peacekeepers as well as civilian housing. Russia responded immediately with a massive ground and air assault and in five days inflicted a heavy defeat on its tiny neighbour, occupying a band of Georgian territory into the bargain.

The conflict had several immediate results.

Already fraught relations between Moscow and Tbilisi plunged to new depths and diplomatic relations were severed.

Russia and three other countries recognised the independence of the breakaway Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

And relations between Russia and the West – the US and the EU – deteriorated to their worst level since the collapse of the USSR – there was even talk of a new Cold War from western politicians.

The Cold War analogies led some commentators to argue Russian foreign policy had taken a decisive anti-western turn and things could and/or should never be the same again

Two years later, the one thing that seems unlikely to ever be the same again is the shape and size of Georgia. If recognition from Russia was not enough, the recent International Court of Justice opinion that Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence was not against international law, makes it even less probable Tibilsi could regain control of its lost regions. (more…)

by David Steven | May 15, 2010 | Cooperation and coherence, Europe and Central Asia, North America

When I took part in a wash-up after Copenhagen with a group of American policy makers, I was struck by the sense that, although the summit had been tough for the United States, they took great consolation that the Europeans had had a much worse time of it during the climate talks.

It all made me think of a quip attributed to Gore Vidal: “It’s not enough to succeed. Others must fail.”

Today, Richard posts the following digest of Hillary Clinton’s meeting with the UK’s new Foreign Secretary, William Hague (a man she is yet to grow as fond of as she was of his predecessor):

If you want to boil all this down to essentials, I’d suggest the following: (i) Mrs Clinton effectively said, “you’d better show discipline when it comes to the EU”; and (ii) Mr Hague basically said “OK”.

I’d parse the ‘better show discipline’ line in two ways. First, the US wants the UK to play an active role in Europe. Second, it needs the Europeans to respond with one voice to a growing roster of global problems.

Fine.

But to take this beyond complacent lecturing (“we may have a lamentable recent foreign policy record, but at least we’re not as shambolic as those awful old worlders”), the Obama administration needs to do what it can to create an incentive for European cooperation.

When it (i) starts listening to Europeans when they have caucused and arrived at a joint position; (ii) continues to listen, even if it doesn’t agree 100% with the European position; and (iii) foregoes the temptation to divide and conquer by playing favourites among European nations for short term tactical advantage – then, and only then, will I believe that the US is serious once again about the transatlantic relationship.

If Obama’s team wants a ‘disciplined Europe’, good. But it should back this up with its actions. Reward Europe with access when it’s united (as it was, more or less, on climate incidentally). Sideline it when it’s divided. And see the extent to which that makes Europeans pull together in the face of transnational challenges…