by Seth Kaplan | Jun 15, 2012 | Economics and development

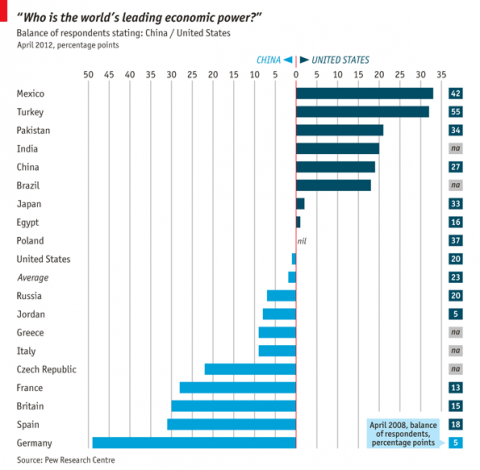

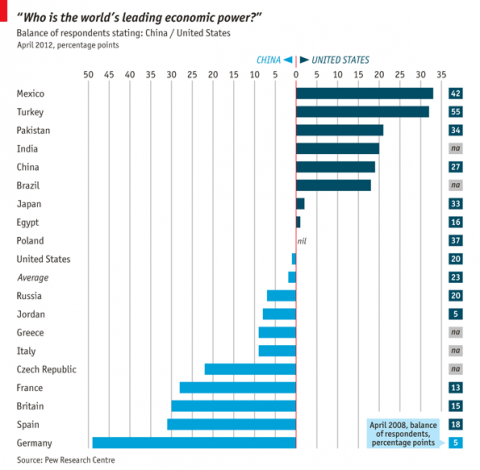

China’s economy remains less than half the size of the United States’. Yet Europeans believe that China is the world’s leading economic power. Few other people make this mistake. What explains this perception–anxiety about the future?

by Alex Glennie | Nov 2, 2011 | Cooperation and coherence, Influence and networks

‘Euroscepticism’ is firmly back on the political agenda following last week’s battle in the House of Commons over whether to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Labour and Lib Dem opposition to the motion ensured its defeat, but an unprecedented 81 Tory MPs defied the party whip to vote in favour, revealing sharp differences of opinion within the Conservative Party.

‘Euroscepticism’ is firmly back on the political agenda following last week’s battle in the House of Commons over whether to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Labour and Lib Dem opposition to the motion ensured its defeat, but an unprecedented 81 Tory MPs defied the party whip to vote in favour, revealing sharp differences of opinion within the Conservative Party.

Where is the public in all of this? Media coverage of this issue generally gives the impression of a nation that is deeply Eurosceptic. Opinion polls indicate that much of the population regards the EU with apathy at best and antipathy at worst. A YouGov poll for Chatham House in June of this year asked respondents to rank international institutions according to how positively they viewed them (with 10 being extremely positive and 0 being extremely negative). The EU scored lowest with a mean score of 4, coming in below the oft-maligned IMF and World Bank. Recent Eurobarometer surveys have found similarly low levels of satisfaction with the EU, with just 35 per cent agreeing with the statement that EU membership has benefitted the UK, compared to 54 per cent who disagree.

However, public attitudes are more nuanced than the topline figures suggest. First, over the last decade, Europe has fallen steadily down the list of issues that voters say they are concerned about, and now sits consistently near the bottom when compared to the economy, crime, immigration and others. There have also been considerable fluctuations in the relative proportions of those who say they would vote to take Britain out of the EU if given the choice, indicated by the results of a series of Ipsos-MORI polls. In October 2011, 41 per cent said they would vote yes in a referendum on staying in, versus 49 per cent who said they would vote no and 10 per cent who were undecided. Yet in 2007, a majority of 51 per cent would have voted to stay in, against 39 per cent who would have voted to get out. It would appear that public opinion is fairly malleable then, responsive to both swings and roundabouts in the economy as well as the rhetoric of political leaders.

We held an interesting debate on these issues at IPPR earlier in the week – the first in a new series of events about the next phase of the European project following the Euro crisis – chaired by the Economist’s David Rennie and with contributions from Shadow Foreign Secretary Douglas Alexander, Conservative MP Douglas Carswell, Ben Page (Ipsos-MORI) and Olaf Cramme (Policy Network). It fairly quickly became a conversation between the two Douglases, although compared to the tone of media commentary on this issue, the discussion was refreshingly civil. (more…)

by Alex Evans | Sep 1, 2010 | Economics and development, Global system

On the fight brewing between the US and Europe over IMF board seats that I wrote about last week, David Bosco at Foreign Policy has been talking to Ted Truman, a former US Treasury official now at the Institute for International Economics. Truman’s take:

First, he argues that the American gambit was not sudden but is a response to what he characterizes as longstanding European intransigence. He believes that Europe has failed repeatedly to respond to American signals of discontent over the past five years. “In 2008 and 2009, they basically said that this issue was not on the table,” he recalls. In that context, the new U.S. position is “an aggressive move in the context of a pretty aggressive defense.”

He also emphasizes the oddity of current European policymaking in a body like the IMF. It’s not as if each of the European seats offers a unique policy perspective. Through the EU, individual member states coordinate their positions in advance. “They just get eight to ten voices every time an issue comes up,” he says. Truman contends that it might actually be better to revert to a smaller board, not least for reasons of cost. IMF executive directors and their staffs are relatively expensive, and in today’s environment of budget-slimming there could be some non-trivial savings for the Fund in a pared-down board.

On this issue, Washington is aligned with India, China and Brazil in an effort to tame traditional European prerogatives. If that trend continues, it could spell trouble for Europe in the world of multilateral institutions.

by David Steven | May 10, 2010 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia

It was a momentous weekend in Brussels, as the European Union struggled to get to grips with the latest episode in the long financial crisis.

Fascinating to see how close it all came to the wire. At midnight, journalists milling around outside the negotiating room were wondering whether “good-quality farmland in neutral, wealthy countries” would be the best place to stash their money if the Euro collapsed.

When the package was finally announced, they were astounded by its size. “We have numbers, and they are much larger than promised,” wrote the Economist’s Charlemagne at 3 am this morning. “We are in shock and awe territory here.” Markets have been duly impressed (it will be interesting to see if this holds as analysts dig into the fine print).

At best however, the deal is a stopgap . There’s been a consensus for months now that Greece will be unable to avoid an eventual restructuring of its debt (hopefully, a planned default). Many believe the same holds for some, or all, of the other PIGS (Ricardo Cabral for one, or Morgan Stanley’s Paolo Batori for another).

My question for Europe’s finance ministers – will you now get ahead of the curve on the Eurozone’s chronic problems, or are you going to drift towards another crisis?

In the wake of Japan’s lost decade, it became fashionable for the British media to excoriate the Japanese government for failing to deal with its zombie banks (and the zombie companies on their balance sheets that had consigned the financial system to the realms of the living dead).

In 2002, the Economist bemoaned ‘the sadness of Japan‘:

From the Japanese government, there will be strenuous efforts to claim that reform is under way, that problems are being solved, that new measures are being considered. The claims will even be true, in a sense: there are plans aplenty, with stages and pillars and fine aspirations. But in a rather stronger sense they will be false: reforms are not being implemented, problems are not being solved, new measures are likely to make as little progress as the old ones. Japan is in a slow, so far genteel decline.

Perhaps the saddest thing is that there is nothing new about this. The turn in Japan’s fortunes began in 1990 with the crash in its stock and property markets, and then took firm hold in the mid-1990s when banks started to crumble and public borrowing lost its ability to keep the economy growing. As long ago as September 26th 1998, The Economist lamented on its cover about “Japan’s amazing ability to disappoint”.

But doesn’t Europe now have at least one zombie country in its midst- and possibly more (and zombie banks too, exposed to these countries’ debt)? And won’t the Eurozone continue to suffer almost indefinitely if it fails to take decisive action to take these countries through an orderly bankruptcy and get them back on a sustainable track?

(As an addendum, what about the UK? Could it become a zombie too? No. If markets stop funding British government debt, then the end will be swift. The IMF may ease the restructuring, but there’s no Eurozone for the UK to hide in. Relatedly, pre-election thoughts on how a Cameron-led government should deal with Europe, the economic crisis, and a volatile world.)

by Alex Evans | Oct 4, 2009 | Europe and Central Asia, UK

Now that ratification of Lisbon has moved a big step closer (not only with the Irish yes, but also the news that Czech President Vaclav Klaus is likely to bow to pressure not to hold it up), the idea of Tony Blair being the first permanent President of the European Council is looking a lot more likely. Predictably, a large strand of liberal opinion is furious about this. As an e-petition currently being circulated has it,

In violation of international law, Tony Blair committed his country to a war in Iraq that a large majority of European citizens opposed. This war has claimed hundreds of thousands of victims and displaced millions of refugees. It has been a major factor in today’s profound destabilisation of the Middle East, and has weakened world security. In order to lead his country into war, Mr Blair made systematic use of fabricated evidence and the manipulation of information …

The steps taken by Tony Blair’s government, and his complicity with the Bush administration in the illegal programme of “extraordinary renditions”, have led to an unprecedented decline in civil liberties.

All true. But for all that, Blair is far and away our best option for the job.

(more…)