by Alice Macdonald | Apr 21, 2016 | Climate and resource scarcity, Cooperation and coherence, Global Dashboard, Influence and networks

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6f1FpJxLGFg[/youtube]

On April 22nd, about 160 countries are expected to officially sign the Paris Climate Agreement which was negotiated last year. It was one of the two international deals agreed by Heads of State in 2015 which made it such a critical year for international development and for millions of activists and citizens around the world. The second was the agreement of the new Sustainable Development Goals- or the Global Goals – which provide a new and ambitious framework to tackle poverty, inequality and climate change.

The global coalition – action/2015 – was formed because of those two historic deals. It brought together civil society around the world – from the big organisations like World Vision to small grassroots groups and networks– to campaign together across sectors and geographies. As Head of the action/2015 campaign for Save the Children, one of the organisations at the heart of the action, I was one of those campaigners.

With the signing of the climate deal this week and the independent evaluation of the campaign concluded (which you can read here), it feels like a pretty good time to step back and reflect on what worked, what didn’t and what we can learn for the future

When action/ 2015 was first conceived, lots of people were sceptical. And there’s no denying it was ambitious. The idea of bringing together diverse sectors from climate and development across hundreds of countries with different cultures, languages and attitudes to campaigning in just under two years seemed pretty unachievable to many – especially those who had worked in coalitions before! I have to admit when I started on the campaign at the end of 2014 I had similar qualms – could we really pull it off?

But, I’m proud to say the campaign proved the sceptics wrong. The official evaluation highlights in its 7 main conclusions that one of the key impacts of the campaign was that global civil society groups learned to work together. I would caveat that to say that action/2015 helped them to work better together but the sense of solidarity that grew across the campaign was undeniable. it worked because of the campaign’s loose, fluid structure that meant individual organisations or national coalitions could take the content and tactics they liked, adapt them to their own contexts and leave the bits that didn’t work for them. It was also crucial that this was not a campaign with specific policy asks but was focused on mobilisation.

“The main reason we got involved is because it is a unique campaign. It links global to local, and it aims at mobilising citizens. This was unique meaning that we usually target policy makers, but this was more about masses, numbers, reaching out to everybody. And that attracted me. It was something different.” , Participating organisation, Africa

The other main point that leaps out is the conclusion that ‘action/2015 made meaningful steps towards Southern ownership of a global campaign’. By the end of the campaign 80% of its members were based in the South. The campaign’s centre of gravity definitely felt like it was much more in the cities, towns and villages of India or the streets of Costa Rica and Kenya than Northern capitals.

Big NGOs did play a driving role in the campaign, but in a different way than in previous campaigning. I’m proud that Save the Children took much more of a backseat, deploying resources and support to help civil society all over the world campaign.

It certainly wasn’t an easy campaign and we didn’t get everything right. In many ways we were building the car as we were driving and there’s no doubt with more resources and time we could have achieved more but what the campaign did achieve should not be dismissed. Millions of people mobilised to take action, a new generation of activists inspired, some amazing backers from Malala to One Direction, a strong basis laid to ensure the successful implementation of both deals and a new model of campaigning.

So the big question now is what next? The evaluation sets out 10 lessons. Some of them might sound obvious like leaving enough time for planning and the importance of proper evaluation but these are often the mistakes made again and again.

Tax injustice, the refugee crisis and global health challenges like Zika – these are all issues that have been hitting the headlines. The new frameworks we have could arguably have helped prevent many of the inequalities that lead to and exacerbate s these and similar crises and they can definitely help reduce their likelihood in the future. But that won’t happen unless people know about the deals and are able to hold their leaders to account. That’s why a sustained and concerted campaign building on the momentum and goodwill generated last year is vital. We need to campaign less about the frameworks themselves but campaign about them through the real life lens of people’s lives.

Campaigning is about trying new things and being prepared for some things not to work.Yes if we were to do action/2015 again I’d do some things differently but I would keep the same level of ambition and the open, inclusive campaigning model. action/2015 has built a huge appetite for campaigning together all around the world which we must harness. I can’t put it any better than one of the action/2015 campaigners from Africa – “I got more friends and when you have more friends you feel stronger.

by Alex Evans | Sep 15, 2015 | Global Dashboard

1.Whatever you think about Jeremy Corbyn, it is kind of astonishing to see a party leader who goes straight from being elected to participating in a march for refugees’ rights. I’ve grown up used to Labour leaders who pitch themselves at Middle England while assuring us Party members sotto voce that they’re one of us really. It feels weird to have a Labour leader pitching himself at me.

2. I do though wonder about ‘polarisation’ and the risk of issues becoming partisan where they weren’t before. Look at climate change. Once there was a consensus on this; now, it’s arguably the single biggest dividing line between left and right, partly because us lefties made it ‘our’ issue (thanks, Naomi). Is the same thing going to happen on more issues if a leader like Jeremy Corbyn champions them? If so, would that be a good or a bad thing?

3.Which leads me to a bigger underlying question: now that Jeremy Corbyn is our leader, do we have a plan for reaching out to the public and taking them with us? Or is this going to be like all our Facebook walls, where we just talk to ourselves?

4. The right clearly takes the latter view and is giddy with excitement. Janan Ganesh in the FT today: “If David Cameron showed up to parliament in his Bullingdon Club tailcoat to announce the sale of Great Ormond Street children’s hospital to a consortium led by ExxonMobil, his Conservatives would still be competitive against Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour at the next election.” It would be nice to defy these expectations.

5. For the right / New Labour / Blairites, and not a few Brownites, this means they need to (how to put this?) shut the f**k up and acknowledge Corbyn’s overwhelming mandate. They were the first to expect loyalty to the leader when they ran the show. For them to be muttering about ousting Corbyn – as lots of them are privately, and some even publicly – is totally inappropriate.

6. For the left / people who voted for Corbyn, the quid pro quo – one that will be just as hard for them as shutting up will be for the New Labour folk – must be that they have got to let go of this instinct to denounce any questioning of anything Corbyn says / does / has ever done / has ever said as part of a conspiracy to ‘smear’ their guy. Heaven knows Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have never felt shy of living out their view that debate within the Party is healthy…

7. …which is just as well, because we have a lot to debate right now, and it would be nice to be able to do so without being at each other’s throats. Truth is, I feel deeply conflicted about the result. I voted Kendall, Cooper, Burnham because I want Labour to win elections; yet my main feeling about the Blair and Brown eras is one of disappointment. Sure, there were successes – but bloody modest ones, given the scale of the 97 landslide. I want a radical alternative for the 21st century.

8. But I feel uneasy that so much of the Corbyn agenda seems so 20th century: more Socialist Worker than New Economics Foundation. I want us to build new institutions, not just defend the old ones. Above all a lot of it seems deeply statist where I’ve been hoping for something that’s much more about decentralisation and communities. There’s been a lot of good thinking about this in recent years from people like Jon Cruddas and Paul Hilder (see this piece of mine from back in May for links to their stuff). I don’t see much of it represented in Jeremy Corbyn’s platform.

8. On that note, as much as the media try to spin this as New versus Old Labour, there’s actually something much more interesting going on here, as Paul Mason noted a few days ago. Jeremy Corbyn surged to victory by talking about “progressive, left, green, feminist and anti-racist values” – messages that appeal to Party members who are “metropolitan, multi-ethnic, networked and … young”. What none of the leadership candidates really spoke to, on the other hand, was the ‘blue’ Labour agenda of “‘reconnecting’ with the working class base … old Labour voters worried about migration, declining communites etc.”

9. Whereas Tom Watson does align much more with these ‘blue’ Labour values. So for me the question I’m most fascinated by is this: will the ‘red’ and ‘blue’ Labour worldviews and their new standard bearers, Jeremy Corbyn and Tom Watson, be able to work together? Is there some kind of synthesis out there waiting to be found between these two very different takes on what the left should look like? Or is it just a matter of time before the gloves come off? I hope the former; even then, it may not be enough. But let’s go for it.

10. After all, who the hell knows about anything any more. Everyone was wrong about the general election. Everyone was wrong about Corbyn’s chances of winning the Labour leadership. Maybe they’re all wrong about his chances in the next general election too. (As the Daily Mash put it, “A man who just defied expectations to get elected definitely could not win an election, it has been confirmed”.) For sure if there’s another financial crisis then all bets are off: the Conservatives won’t have Labour to blame this time, and with nothing left in the kitty to bail anyone out it could look a lot nastier than the last one.

by Molly Elgin-Cossart | May 15, 2014 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global system

The post-2015 development agenda offers an extraordinary opportunity to tackle the world’s two most pressing challenges—poverty and climate change. A recent report from the Center for American Progress outlines a practical strategy for policymakers to ensure the new framework tackles both.

While it is sometimes tempting to despair that countries around the world are incapable of crafting multilateral solutions that are equal to the world’s most pressing challenges, there are tremendous opportunities for international agreements to bring about real change and accelerate progress.

In 2015, a pair of international summits – one to agree on a set of sustainable development goals, the other a new climate agreement – present a tremendous opportunity. These efforts can and should complement one another.

Where countries failed to fully integrating environmental concerns into the Millennium Development Goals, they have an unprecedented opportunity now to ensure that the new goals complement and mutually enforce global development and climate solutions.

In a new report from the Center for American Progress, a couple of colleagues and I outline specific, measurable targets to be incorporated into future development goals. These targets focus on specific actions that fight poverty and reduce the catastrophic effects of climate change, and support sustainable agriculture and food security, economic growth and infrastructure, sustainable energy, ecosystems, and healthy lives.

If adopted as part of the post-2015 development agenda, these targets would help drive investments and sensible actions by local and national governments, multilateral development banks, international organizations, and the private sector to end poverty and build a more resilient and sustainable future for generations to come.

by Alex Evans | May 13, 2014 | Climate and resource scarcity, Global Dashboard

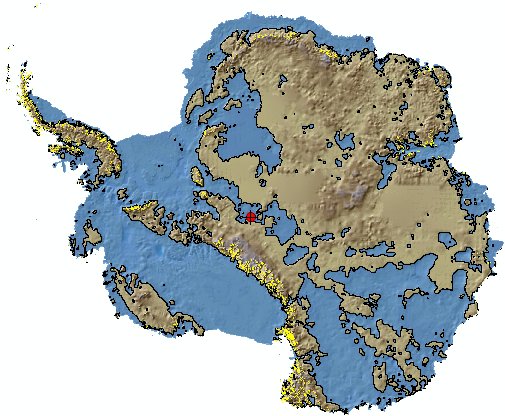

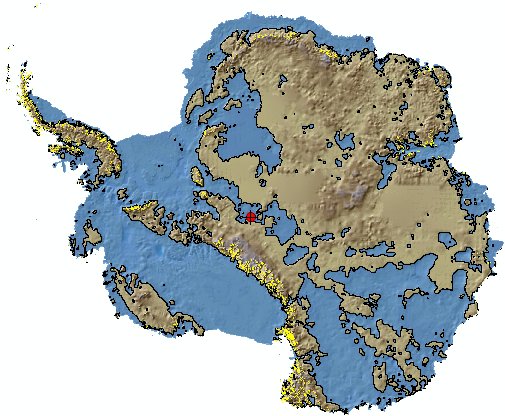

Yesterday’s findings from two scientific teams that a large section of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has now started to collapse (almost certainly unstoppably, implying 10 feet or more of long term sea level rise), is relevant to pretty much everyone around the world. But for us Brits in particular, the prospect of the disappearance of so much of Antarctica has a particular resonance, coming as it does just a couple of years after the centenary of the deaths of Robert Falcon Scott and his companions in the race to the South Pole.

Scott’s last expedition didn’t cross the West Antarctic Ice Sheet on their way to the Pole; instead, they landed just to the east of the WAIS, at the edge of the Ross Sea, and made their way to the Pole over the Ross Ice Shelf.

They built their HQ, seen above, on Ross Island, at a place called Cape Evans – named, as it happens, for my great granddad, Teddy Evans, who was second in command of the expedition. (He was also one of the few who survived; he caught scurvy on the way to the Pole, and was hauled back by his companions William Lashley and Tom Crean – thanks to whom I’m here to write this blog post.) He’s just to Scott’s right in the photo above, taken at Cape Evans on Scott’s birthday in 1911.

But now the Ross Ice Shelf is melting too – not as fast as the WAIS, admittedly, but melting from underneath all the same, rather than just calving icebergs the way it always used to. Same story with Antarctica’s other giant cold-cavity ice shelves, Filchner and Ronne.

There’s a certain sad irony here in that the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust recently completed a successful appeal to preserve Scott’s hut at Cape Evans – a place that, as David Attenborough noted when he went there, is

“a time warp without parallel – you walk into Scott’s hut and you are transported to the year 1912 in a way that is quite impossible anywhere else in the world. Everything is there.”

But while the hut will stay the same, the continent that my great granddad and his fellow expeditioners would have looked out at whenever they stepped outside is disappearing. Not too many generations from now, only the bedrock will be left – and even that, rapidly disappearing under the waves.

See this companion post, also published today, for a short guide to other climate ‘tipping points’ – and a few links to what you can do to help prevent us from sleepwalking over any more of them.

by Alex Evans | May 13, 2014 | Climate and resource scarcity, Global Dashboard, Global system

Yesterday’s news that we now appear to be on course for the unstoppable and irreversible loss of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) – the largest ice body in the world (for now, anyway) – means that we’re now probably past two key climate tipping points, the other being the loss of summer Arctic sea ice. So this is probably a good time to post a quick overview of all of the main climate tipping points: if you’re not familiar with this list, you should be…

Below is a quick guide, adapted from a chapter by Exeter University’s Tim Lenton in his and Tim O’Riordan’s book on the same subject. The book was published last year; as you can see, scientific consensus at the time was that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet “appears to be further from a tipping point than its Greenland counterpart”. So much for that estimate.

- Arctic sea ice loss underwent a new record summer loss of area in 2012, breaking the previous record of 2007, and now covers only half the area of the late 1970s when satellites first began monitoring it. Current projections suggest we’re looking at complete loss of Arctic summer sea ice within decades. Already, the changing ice cover is changing air circulation patterns, and leading to cold winter extremes in Europe and North America.

- The Greenland ice sheet may be nearing a tipping point beyond which it is committed to shrink; here too, the summer of 2012 saw record melting. Ice loss would probably take place over centuries, so this form of change wouldn’t be abrupt – but it might well be irreversible, and could ultimately lead to 7 metres of sea level rise, including up to half a metre this century.

- The West Antarctic ice sheet appears to be further from a tipping point than its Greenland counterpart, but has the potential for more rapid change, and hence bigger impacts in the near term. If warming exceeds 4º Celsius, the current best guess is that the West Antarctic ice sheet is ‘more likely than not’ to collapse, causing sea level rise of 1 metre per century and 3-4 metres in total.

- The Yedoma permafrost in Siberia contains massive amounts of carbon – potentially up to 500 billion tonnes of it, about the same as has been emitted by human activity since the start of the industrial revolution. If decomposition inside the permafrost starts to generate enough heat, all of the permafrost could tip into irreversible, self-sustaining collapse, generating a “runaway positive feedback” with emissions of 2-3 billion tonnes of carbon a year, or about a third of current fossil fuel emissions. The current best guess is that this would not happen before regional warming of 9º Celsius, but that could be closer than we think: in 2007, for instance, Arctic surface temperatures jumped 3º Celsius.

- Ocean methane hydrates are thought to store up to 2,000 billion tonnes of carbon under the seabed. As the deep ocean warms, this frozen reservoir of methane could conceivably melt, causing an abrupt, massive release of the gas – which is four times as potent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide. This is probably at the least likely end of the spectrum, but the impacts if it happened would be extreme.

- The Himalayan glaciers could lose much of their mass over the coming century, with the change becoming self-amplifying as exposure of bare ground increases the amount of sunlight energy absorbed at the Earth’s surface rather than reflected back into space. Scientists are so far unsure as to whether a large-scale tipping point could apply to this trend.

- The Amazon rainforest experienced severe droughts in both 2005 and 2010 – in both cases, turning the forest into a source of carbon rather than a sink for absorbing it. If, as is currently happening, the dry season continues to lengthen, and droughts get more frequent and severe, then the rainforest could reach a tipping point, with up to 80% of trees dying off. Widespread dieback is expected at increases of over 4º Celsius, and could be committed to at much lower temperature increases – long before we notice it happening.

- Western Canada’s boreal forest is currently suffering from an invasion of mountain pine beetle, leading to widespread dieback which has already turned the forest from a source to a sink. More widespread die-off could happen in future at global average warming of more than 3º Celsius, further amplifying global warming.

- Tropical coral reefs are already experiencing bleaching as oceans warm up, and may be nearing a ‘point of no return’. Further risks come from the increasing acidification of the oceans, which could see up to 70% of corals in corrosive water by the end of this century.

- The Atlantic thermohaline circulation (THC) – in effect, a massive oceanic conveyer belt that drives the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift, and which helps keep northern Europe much warmer than it would otherwise be – could shut down altogether if enough freshwater dilutes the ocean’s salinity; current best guesses are that this could happen at global average warming of over 4º Celsius. A weakening THC could also drive an additional quarter metre of sea level rise along the north-eastern seaboard of the United States.

- The Sahel and West African Monsoon has experienced rapid changes in the past, including a catastrophic drought that lasted from the late 1960s through to the 1980s, and could be disrupted anew by changes to the THC. The Indian Summer Monsoon, meanwhile, is already being disrupted and rice harvests damaged, in particular by the cloud of brown haze that now sits semi-permanently over the Indian sub-continent.

Of course, the really big question in each case is exactly where the tipping points lie, and what level of temperature increase might push us over the threshold. Some research suggests that warning of 1º Celsius over the average temperature of the 1980s and 1990s would be dangerous; other recent work suggests that 4º could be where the danger zone begins.

But again, note that the best guess just one year ago was that it would take 4º of warming to cause the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to collapse; in the event, current warming of 0.7º above pre-industrial levels seems to have been enough to push us over the edge. It’s a salutary reminder of how little we know about climate tipping points – and hence just how risky and high stakes a situation we’re in.

And in all scenarios, the key point is that these kinds of temperature increases are exactly where our current trajectory is headed: current policies have us on track for 3.6-5.3 degrees Celsius of warming, according to the IEA. In the worst case scenario, Tim Lenton observes, we could slide into

“…’domino dynamics’, in which tipping one element of the Earth system significantly increases the probability of tipping another, and so on … on several occasions in the past, the planet was radically reorganized without there being any sign of a particularly large forcing perturbation.”

Wondering what you can do in the face of such relentlessly gloomy news? Get hold of any policymaker you can and ask them whether they support a binding global carbon budget, and fair – i.e. equal per capita – shares of it for all the world’s people. Ask whichever NGO you support whether they’re calling for the same thing at the Paris summit next year. And don’t take any shit from anyone about how technology and voluntary action are going to do the business without anyone having to take any tough decisions.

(See also this companion post, also published here today, for a slightly different take on the loss of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.)