by Ryan Gawn | Nov 8, 2015 | Cooperation and coherence, Global system, Influence and networks, UK

This is the third in a series of blogs on the upcoming Spending Review, and how Britain maximises its influence and soft power across the world at a time of declining budgets. This focuses on the BBC World Service, “Britain’s gift to the world”. Find the others with the following links: FCO, British Council.

Other UK soft power assets fall into the “unprotected” category and are at risk of cuts. Since the Chatham House / YouGov Survey began polling in 2010, BBC World Service radio and TV broadcasting has been seen by UK opinion-formers as the UK’s top foreign policy tool, consistently ranking higher than all other foreign policy “assets”.

Broadcasting to 210m people every week and with a budget less than half that of BBC2, the World Service faces increasing challenges in the form of domestic and international competition, technical change, and a legacy of underinvestment. FCO funding was cut by 16% in 2010, leading to the departure of about a fifth of  its staff. This has had an impact – in 2005 the organisation provided services in 43 languages, now down to 28. In contrast, there is increased competition – following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets with state journalists now pumping out content in more than 60 languages. Lacking first mover advantage, it is clear that competitors have strategic ambitions. Yu-Shan Wu of the South African Institute for International Affairs comments, “Since the Beijing Olympics, we have seen increased efforts to provide China’s perspective on global affairs, signalling relations with Africa have moved beyond infrastructure development to include a broadcasting and a people-to-people element. There are now regular exchanges between Chinese and African journalists, and it is clear that China is stepping up and laying the foundations for a more concerted public diplomacy effort in the region.”

its staff. This has had an impact – in 2005 the organisation provided services in 43 languages, now down to 28. In contrast, there is increased competition – following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets with state journalists now pumping out content in more than 60 languages. Lacking first mover advantage, it is clear that competitors have strategic ambitions. Yu-Shan Wu of the South African Institute for International Affairs comments, “Since the Beijing Olympics, we have seen increased efforts to provide China’s perspective on global affairs, signalling relations with Africa have moved beyond infrastructure development to include a broadcasting and a people-to-people element. There are now regular exchanges between Chinese and African journalists, and it is clear that China is stepping up and laying the foundations for a more concerted public diplomacy effort in the region.”

From April last year, the World Service ceased to be funded by the FCO, and is now resourced by a share of the BBC licence fee. Although its budget was increased by the BBC in 2014 (up by £6.5m to £245m), the BBC itself faces many of its own funding challenges. In July, the Chancellor called on the organisation to make savings and make ‘a contribution’ to the budget cuts Britain is facing. Ministers asked the BBC to shoulder the £750m burden of paying free licence fees for the over-75s, and later that month unveiled a green paper on the future of the broadcaster which questioned if it should continue to be “all things to all people”. In the same month, the organisation announced that 1,000 jobs would go to cover a £150m shortfall in frozen licence fee income.

The World Service is somewhat insulated from wider BBC cuts, as the BBC has to seek the Foreign Secretary’s approval to close an existing language service (or launch a new one). Nevertheless, in early September, Director-Genera l Tony Hall made the first of a series of responses to the green paper. Making a “passionate defence of the important role the BBC plays at home and abroad”, he unveiled proposals for a significant expansion of the World Service, including; a satellite TV service or YouTube channel for Russian speakers, a daily news programme on shortwave for North Korea, expansion of the BBC Arabic Service (with increased MENA coverage), and increased digital and mobile offerings for Indian and Nigerian markets. Interestingly, the proposals sought financial support from the government, suggesting matched funding, conditional upon increased commercialisation of the BBC’s Global News operation outside the UK.

l Tony Hall made the first of a series of responses to the green paper. Making a “passionate defence of the important role the BBC plays at home and abroad”, he unveiled proposals for a significant expansion of the World Service, including; a satellite TV service or YouTube channel for Russian speakers, a daily news programme on shortwave for North Korea, expansion of the BBC Arabic Service (with increased MENA coverage), and increased digital and mobile offerings for Indian and Nigerian markets. Interestingly, the proposals sought financial support from the government, suggesting matched funding, conditional upon increased commercialisation of the BBC’s Global News operation outside the UK.

More on the expansion plans here.

by Ryan Gawn | Jul 22, 2015 | Conflict and security, Cooperation and coherence, Global system, Influence and networks, UK

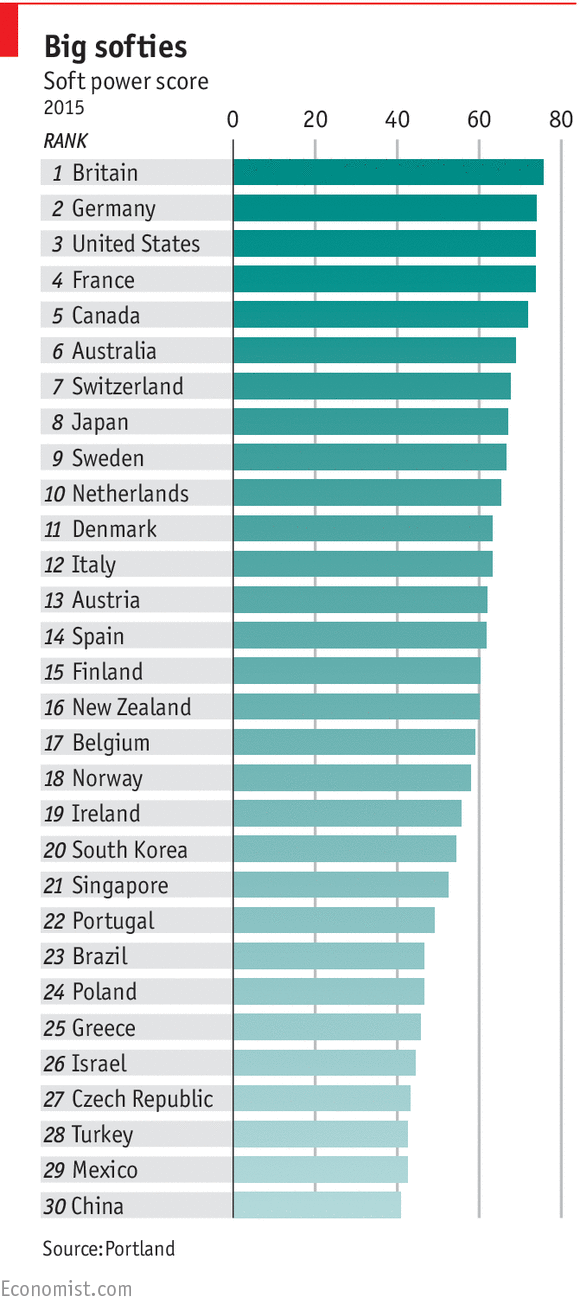

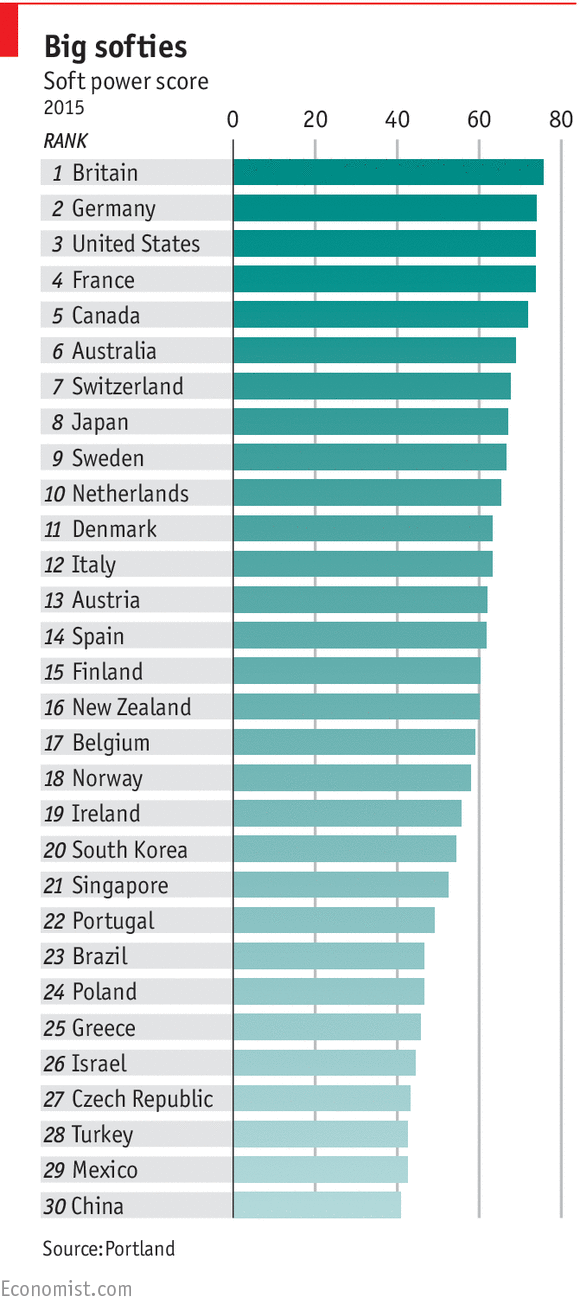

Last week saw the launch of a new global #softpower report, ranking the UK at the top of a 30-country index. Compiled by Portland, Facebook and ComRes, the report is described by Joseph Nye (who coined the term in 1990) as “the clearest picture to date of global soft power”, and has ranked countries in six categories (enterprise, culture, digital, government, engagement, education).

There are quite a few of these indices around now, with varying methodologies – nevertheless, this is the first to incorporate data on government’s online impact and international polling. Who’s at the top of the tables isn’t really surprising (the top 5 countries – UK, Germany, US, France, Canada – are identical to the top 5 in the Anholt-GFK Roper Nation Brand Index, but with a slight reordering of ranking). The US, Switzerland and France topped the specific categories, and although not first place in any of the categories, the UK ranked highest overall, reflecting its strength in culture, education, engagement & digital. More on the UK later.

What is really surprising is that China finishes last. Following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets (such as the Xinhua news agency, aid/ development projects), at a time when others have been paring back their ambitions. Nevertheless, the impact of this investment isn’t borne out in the results, likely hindered by negative perceptions of China’s foreign policy, questionable domestic policies and a weakness in digital diplomacy. China came out strongest in the culture, likely reflective of the many Confucius Institutes dotted around the globe.

There are a few other interesting nuggets:

· Broader power trends are increasing the need for soft power – 3 factors driving global affairs away from bilateral diplomacy and hierarchies and toward a much more complex world of networks:

1. Rapid diffusion of power between states

2. Erosion of traditional power structures

3. Mass urbanisation

(more…)

by David Steven | Oct 21, 2010 | What we're watching

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6Ye06r2_n8[/youtube]

by David Steven | Apr 29, 2010 | Economics and development, UK

If the BBC leaders’ debate tonight devotes more time to bigotgate than to housing, I am going to dedicate the rest of my days to working for the Corporation’s demise.

Britain’s unsustainable housing market is at the root of many of the country’s problems and could wreak appalling damage on voters during the next parliament. It must feature in the debate.

Someone should start by reminding Gordon Brown of a promise he made in his first budget speech in 1997:

Stability will be central to our policy to help homeowners. And we must be prepared to take the action necessary to secure it. I will not allow house prices to get out of control and put at risk the sustainability of the recovery.

As I argued recently:

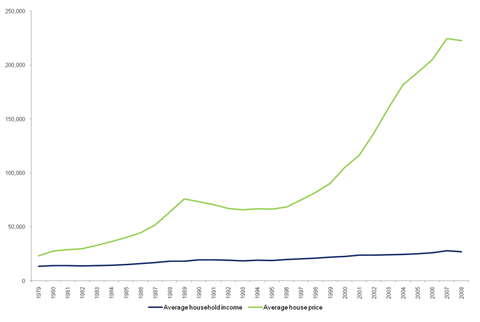

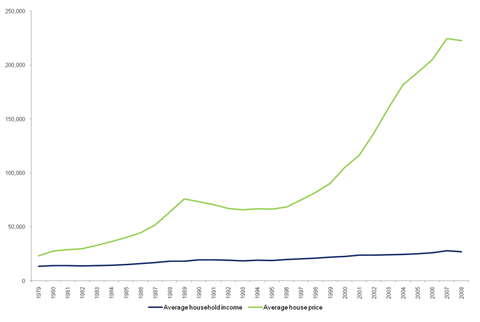

When Brown spoke, the average house cost £75k – about £10k above the early 1990s nadir. A long long boom was just beginning. Prices would peak in February 2008 at an average of… £232k!!!

In other words, Brown promised not to let house prices spiral out of control and then allowed them to treble, during a period when household disposable income increased by only 30% or so.

2007 saw what is often called a housing price crash, but as this graph shows, it was really only a blip.

As the government pumped money into the economy and pushed interest rates to unprecedented low levels, the bubble started to inflate again. House prices are now back to the levels of June 2007.

Second guessing the housing market is a mug’s game, surely this is unsustainable. British houses are overvalued by nearly a third, according to one measure. Worse is the amount of mortgage debt outstanding – $1.238 trillion. By comparison, government debt is ‘only’ £950 billion.

Low interest rates and buoyant employment (relative to the economy’s woeful performance) have kept householder’s head above water – but the highly-indebted remain highly vulnerable to any increase in interest rates or to further job losses.

My best case for the housing market is a long period of stagnation (we desperately need lower prices). Worst case would be a sudden, vicious and self-fulfilling collapse. I believe this is currently the most serious economic risk facing the British people (one which is, of course, interrelated to Europe’s sovereign debt problems).

So what do the major parties have to say about this in their manifestos?

- Labour wants to expand home ownership and exempt all houses under £250k from stamp duty (likely to push house prices up). It says it will build 110k houses over two years (likely to push prices down).

- The Conservatives promise to exempt first time buyers from stamp duty if their house costs less than £250k. It wants to put communities in charge of planning, which is highly likely to reduce the number of houses built.

- The Lib Dems plan to use loans and grants to bring 250k empty houses back into use.

Pretty weak beer, all told. No party questions the shibboleth that Britain needs more homeowners. None is prepared to explain how they will manage risks that have been increased by the response to the financial crisis.

Far less do they have policies to fulfil Brown’s promise from 1997 – to end boom and bust in the housing market radical proposals (see my Long Finance paper) to prevent the mortgage market from screwing borrowers every twenty years or so.

So here’s my question for tonight’s debate:

In 1997, Gordon Brown promised he’d never let house prices get out of control again, but then presided over a housing bubble that has left British householders owing £1.2 trillion on their mortgages. In government, what will you do to stop the housing dream from becoming a housing nightmare?

by David Steven | Oct 23, 2009 | UK

Hats off to the BBC.

It could have announced that Nick Griffin was appearing on Question Time a couple of days ago, and then hoped the whole thing would pass off as quietly as possible.

But that would have been boring. Positively Reithian. How much better to turn the appearance of the BNP leader into… an event! Here’s how it was done:

Trail the decision to invite Britain’s favourite fascist onto Question Time at the end of the silly season, ensuring a six-week, slow burn for the story.

Begin to run cross-platform coverage under suitably-provocative banners like “Who’s Afraid of the BNP?”

Use party conference season to gin up interest in who else will be on the show, making sure the big announcements (a cabinet minister!) get plenty of coverage.

Wait eagerly for the inevitable attacks on your decision to give the BNP airtime.

Get your top brass to respond to them with much earnest head-shaking (“this is hurting us, more than it’s hurting you… but we’re doing it for the children democracy”).

As the big day approaches, up the pace of your coverage – a special on Newsnight (make that two!), prominent slots on all of your news and current affairs programmes, regular briefing for the print media.

Then the day of broadcast…

…rile up the demonstrators, leave the gates open long enough for them to invade your offices, then switch on the 24-hour rolling news coverage…

…fuel speculation over whether the guest-of-honour will make it through the crowds, then smuggle him in through a back entrance (having tipped off the paparazzi so they get good snaps)…

…make the whole thing interactive (Have Your Say! phone-ins, Twitter, etc) – a chance for everyone to be involved.

As soon as the programme is over, start milking it for all it’s worth. Get Richard Bacon to ask a BNP councillor how well he thinks his leader’s done. Tell Nicky Campbell to use his phone-in to ask “Was Nick Griffin’s appearance on Question Time a triumph for democracy?” And, of course, Join the Discussion on Our Blog! (how could you not?).

Now obviously, there were some missed opportunities (why no BNP theme for EastEnders? And surely Radio 3 should have had a Wagner special) – but all in all, a proud day for our public service broadcaster.

Hopefully, in its review of the affair, the BBC Trust (“getting the best out of the BBC for licence payers”) will not look simply at Question Time itself, but will explore the multi-media phenomenon in the round.

How many broadcast hours were dedicated to the event? Website inches? Weeks of work by the BBC’s queens and kings of media hype?

And how good were the results from making the news, rather than just reporting it? What were the ratings/hits/coverage like? How long has the BBC spent on the front pages? Are people talking about its ‘event’ at work?

its staff. This has had an impact – in 2005 the organisation provided services in 43 languages, now down to 28. In contrast, there is increased competition – following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets with state journalists now pumping out content in more than 60 languages. Lacking first mover advantage, it is clear that competitors have strategic ambitions. Yu-Shan Wu of the South African Institute for International Affairs comments, “Since the Beijing Olympics, we have seen increased efforts to provide China’s perspective on global affairs, signalling relations with Africa have moved beyond infrastructure development to include a broadcasting and a people-to-people element. There are now regular exchanges between Chinese and African journalists, and it is clear that China is stepping up and laying the foundations for a more concerted public diplomacy effort in the region.”

its staff. This has had an impact – in 2005 the organisation provided services in 43 languages, now down to 28. In contrast, there is increased competition – following a 2007 directive from Premier Hu Jintao, China has been investing heavily in soft power assets with state journalists now pumping out content in more than 60 languages. Lacking first mover advantage, it is clear that competitors have strategic ambitions. Yu-Shan Wu of the South African Institute for International Affairs comments, “Since the Beijing Olympics, we have seen increased efforts to provide China’s perspective on global affairs, signalling relations with Africa have moved beyond infrastructure development to include a broadcasting and a people-to-people element. There are now regular exchanges between Chinese and African journalists, and it is clear that China is stepping up and laying the foundations for a more concerted public diplomacy effort in the region.” l Tony Hall made the first of a series of responses to the green paper. Making a “passionate defence of the important role the BBC plays at home and abroad”, he unveiled proposals for a significant expansion of the World Service, including; a satellite TV service or YouTube channel for Russian speakers, a daily news programme on shortwave for North Korea, expansion of the BBC Arabic Service (with increased MENA coverage), and increased digital and mobile offerings for Indian and Nigerian markets. Interestingly, the proposals sought financial support from the government, suggesting matched funding, conditional upon increased commercialisation of the BBC’s Global News operation outside the UK.

l Tony Hall made the first of a series of responses to the green paper. Making a “passionate defence of the important role the BBC plays at home and abroad”, he unveiled proposals for a significant expansion of the World Service, including; a satellite TV service or YouTube channel for Russian speakers, a daily news programme on shortwave for North Korea, expansion of the BBC Arabic Service (with increased MENA coverage), and increased digital and mobile offerings for Indian and Nigerian markets. Interestingly, the proposals sought financial support from the government, suggesting matched funding, conditional upon increased commercialisation of the BBC’s Global News operation outside the UK.