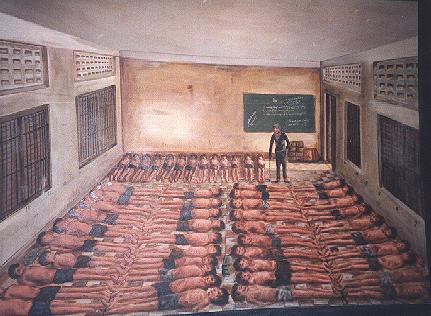

In 1978, Cambodian artist, Vann Nath was locked up by the Khmer Rouge in the S-21 prison. “We were all in one room,” he recalls. “We lay naked down on the floor, packed next to each other in handcuffs, and we tried to sleep.”

The soldiers wore black uniforms. They were young. Some of them were only about 13 or 14 years old, but they had no mercy. Their accusation of “khmang”—enemy—was so powerful. It separated fathers, mothers, children, and siblings from each other.

Every four days, they gave us a bath. They brought hoses up from downstairs and sprayed everyone from the doorway. Each day they would take some prisoners out of my room to be interrogated. Some prisoners came back with wounds or with blood on their bodies; others disappeared. Prisoners started dying in the room, one by one. If a prisoner died in the morning, the guards would not take him out until night. If I needed to defecate I asked the guards to bring the bucket over.

I was lucky. They found out I can draw. They used me a lot to do drawings. All the time they wanted me to draw Pol Pot. They gave me his picture and I would draw. I drew him from different angles and in all different environments. But I never met Pol Pot. He never knew I was the artist that did his pictures.

Of the 14,000 people who entered that prison, Nath was one of only seven to leave. Comrade Duch – the prison commandant – had scrawled ‘keep the painter’ on the list of people to be executed.

After he left prison, Nath painted pictures for Cambodia’s Museum of Genocide. Here is his picture of his cell:

And here’s his picture of waterboarding – hung above the table on which the torture was performed:

Nath remembers the torture:

I could hear screams of pain from every corner of the prison. I felt a twinge of pain in my body at each scream… I could hear the guards demanding the truth, the acts of betrayal, the names of collaborators.

Nath is now seriously ill, with kidney failure and TB that has corroded his spine. He depends on donations and sales of his paintings to stay alive (the Cambodian government has apparently refused to help with his medical costs).

Until 1999, meanwhile, Nath’s ex-captor, Comrade Duch was hiding out, a smiley old man who had converted to Christianity and worked for a development charity. He was then tracked down in 1999 by the photo-journalist, Nic Dunlop confessed his guilt in an interview, and was arrested.

Duch is now held by the UN-backed Cambodia tribunal and was charged in July this year with crimes against humanity. He, too, is ill, with prostate problems, but is receiving medical treatment while in prison. His trial has just started and he will probably be sentenced early next year. He has admitted his guilt and expresses contrition for his actions:

I have done very bad things in my life. Now is the time to bear the consequences of my actions… Then I thought God was very bad. I did not serve God, I served communism. I feel sorry about the killings and the past.

Dunlop believes he may implicate more senior leaders at his trial:

When he spoke in 1999, he accepted his own role in the killings and began to establish a chain of command of how orders were given and carried out and by who. His testimony should be a pivotal moment if he does speak the truth on the stand and so it could be very damaging.

Duch’s trial began with evidence from Nhem En, the photographer whose job it was to take pictures of people just before they were executed:

It’s hard to say if they knew they would die or not. I realised that many times they arrested people who had done nothing. People from my village confessed to being in the CIA. In the end, everyone confessed to something. Most people went on to name every person they could think of as an accomplice before they were killed with an iron bar.

En led a team of six photographers and was careful to minimise contact with the prisoners:

‘Look straight ahead. Don’t lean your head to the left or the right.’ That’s all I said. I had to say that so the picture would turn out well. Then they were taken to the interrogation center. The duty of the photographer was just to take the picture.”

Here are some of his pictures of people waiting to die:

En joined the Khmer Rouge in 1961, when he was ten. He did not leave the party until the mid-90s, when there was an amnesty. In January this year, he made a public apology at a meeting organised by the American ambassador to Vietnam.

En says that he feels both ‘pride and regret’ at the pictures he took. Regret because the photos were sad ones; pride, it seems, because of the international attention they have bought him. He regards his pictures as important historical and artistic artefacts, and uses pictures of his meeting with the Ambassador to raise money for a museum to display his work.

Now a member of the governing party, he is deputy governor for his district. As an important man, he expects to be treated with respect. When summoned to Comrade Duch’s trial, he complained bitterly that he was only given $5 expenses in return for testifying:

I’m living history. They should give me more. The court only offered me $5 and I don’t need that money. I’m a deputy governor! I did my job and I have my pride. Why do they offer me $5? It’s not enough for my breakfast!”

Vann Nath will testify too, but is not interested in stipends. Instead, he waits for justice finally to be done:

What I want to see in my life is for the leaders to face the court and for the trial to determine who is responsible for killing our people. I don’t want to see any leaders killed because I don’t want to see people killed again. I don’t want to see them in prison. I don’t want that.

I just want them to acknowledge that they committed these crimes and explain. That is the most important lesson for our young generation to learn.