Despite being oil rich, Nigeria is desperately energy poor. Per capita electricity consumption is half that of nearby Ghana and even this limited supply is shockingly unreliable.

When the power shuts down – which it does all the time – people sit in the dark or, if they’re lucky, fire up generators that cost the country $140 billion to fuel (add a chunk more for capital and maintenance costs).

On Twitter, there’s an online demonstration going on at the moment against this crazy situation – with huge numbers of tweets using the #lightupnigeria hashtag. “I know a Doctor that once operated in moonlight because the generator refused to come on!” Olunfunmike writes, “Let’s make a change.”

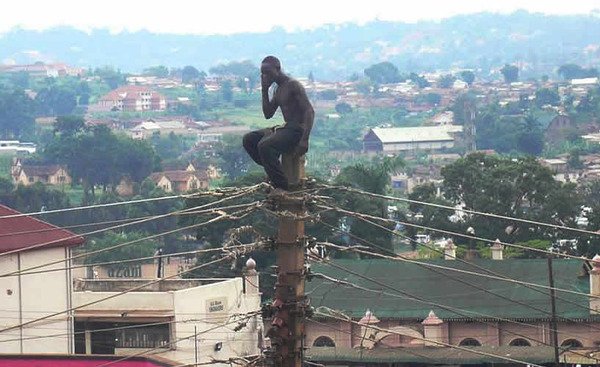

Please join them – and spread the word. (Cool photo – courtesy plastiqq. Find me on Twitter.)

Update: There’s a newish Facebook group too.

Update II: NEPA – Nigeria’s National Electric Power Authority – needs $3.4bn investment over the next five years. At present, however, it’s operating at a huge loss, in part because it only manages to get customers to pay for 60% of the electricity they use (as one customer puts it, “NEPA doesn’t give me light, but at the end of the month a bill would arrive and they would expect me to pay? I don’t think so.”)

President Obsaanjo has pleaded with the company to at least warn customers of impending power cuts (load shedding) before they happen, but many Nigerians believe that’s all he’s doing – pleading for change.

Last year, a Parliamentary investigative panel claimed that $16bn has been spent on the power system, without delivering much increase in supply.

The House of Representatives investigation alleged that Mr Obasanjo’s government had paid millions of dollars to 34 “non-existent companies”. The committee visited the sites where power stations were meant to be built. It found no work had been done at some sites after several years.

Defending his record, Mr Obasanjo said his government had inherited 18 years of neglect in the power generation industry, and had done well to more than double power supply. Gas pipeline vandalism had hampered power generation. One damaged pipeline took two years to repair, he said. To “the uninitiated” it would seem like no work had been done on the power stations, but the reality was that millions of dollars had been “invested”, he said.

But he said the investigation into the power sector may actually hamper improvement, and jeopardise Nigeria’s development. Private partners were being chased away by the probe because they feared being “criminalised”.

Update III: There’s a logo now.

Update IV: This article claims Kwara state has some lessons for the rest of Nigeria, while the UK’s Department for International Development has a case study that illustrates the impact of load shedding on small business:

Badamasi Maiwalda, 32, is an iron bender in Kano, northern Nigeria. He sits under the large mango tree near his workshop looking hopelessly at the powerless electric cables passing overhead. “Many years ago, when there was electricity, I used to make up to 3,000 Naira (about $17) a day. Now I make about N300 ($1.70) on a lucky day when we get the one hour of power which is the most we can ever expect.”

Many of Badamasi’s customers have switched to the bigger iron-bending workshops able to afford diesel generators. “I can’t save enough to buy a generator – I have a wife and three children. But for the past three days there has been no electricity at all. I have made nothing, so there is no food to take home. Without electricity, my family will continue to go hungry.”

This situation has been brewing for years. The Nigerian power sector has seen its generation and distribution capacity become increasingly worn out or damaged, and the population has suffered bitterly as a result. Nowadays only 40% of people have access to power and, for those that do, power cuts and voltage fluctuations are part of everyday life.

Update V: I have always wondered why solar doesn’t do better in cities like Lagos, where it competes against generators on cost. In rural areas, too, solar is cheaper than connecting a village to the grid. According to Kadiri Hamzat, Lagos State Commissioner for Science and Technology:

It costs about 150 million naira (around 1.2 million dollars) to connect each village to the national grid, while the solar energy project costs only about 10 million naira (around 83,000 dollars) per village.

There are some NGOs working on solar – here’s a project from eight years ago. The NGO, WE CARE solar has targeted maternal mortality in a country where 60% of births are at home and where hospital often do not have power. Adele Waugaman writes:

In Nigeria, many women in labor are turned away from rural health clinics simply because there’s no doctor or no reliable electrical power.

In the northern city of Zaria, Laura found that the lone public hospital had only 160 hospital beds for a population of 1.5 million, and that electricity was available no more than 12 hours a day.

There was no running water in the delivery room, and no blood bank because intermittent access to electricity meant the blood couldn’t be refrigerated reliably.

Laura’s “solar suitcase”, a kit of solar panels and rechargeable batteries, can light operating and delivery rooms, run a blood bank refrigerator and power two-way radios so that staff can call in off-duty doctors for emergency surgery.

Recently, the NGO has bought a blood bank refrigerator that will be solar powered.

This essential piece of emergency equipment will enable mothers who are bleeding to immediately obtain life-saving blood products. Compare that to the current system of transfusion, in which families must first arrange for blood donors to come to the hospital and be tested for suitable matches before a transfusion can occur. I have literally been here when women have bled to death in the middle of the night because there is no transportation available to get family members to rural villages to hunt for possible blood donors. As hemorrhage is the number one cause of maternal mortality, there couldn’t be a more important piece of equipment in the hospital.

Solar water heating also has huge potential, with the United States Embassy in Abuja said to already have a system installed. This paper from Nigeria’s National Centre for Energy Research and Development surveys the potential of the technology and obstacles to its wider take-up. There is also some interest in solar cooking.

Surely, with the right product at the right price, solar has the potential to spread in Nigeria in the same way that mobile telephones have – running rings around an inefficient fixed network, run by a state-owned monopoly.

As a coda, high import tariffs are a problem for solar in some Africa countries (e.g. Namibia). Solar panels, however, are zero-rated in Nigeria and in Ghana too.

Update VI: The One Laptop Per Child foundation gave 300 laptops to L.E.A. Primary School Galadima on the outskirts of Abuja.

Nice idea, but the lack of electricity has hugely complicated the initiative – and made it much more expensive. According to a project review (which recommends electrifying the school, but does not seem to consider the subsequent impact of load shedding):

The foundation also gave Galadima School sixty extra XO Laptop rechargeable batteries, four sets of solar panels (installed on the roof) and gang chargers to charge the laptop batteries so the children can work on their laptops more continuously. However this arrangement was designed for remote rural areas and is far from optimal.

Alteq has contributed a generator that runs on gasoline and provides electricity…However, the generator broke down and burned the UPS for the Internet, and it is insufficient for all the power needs of the school… Also, we have to keep in mind that the generator:

- has to be carried out of and into the principal’s office before and after it’s used.

- has to be taken to the gas station to be filled up.

- requires servicing, which can take several days.

The classrooms for primary 1 and primary 2 receive very little natural illumination. And all the classrooms fall into almost complete darkness when it rains, because the windows have to be closed and thus, the sunlight is blocked out. All of which makes it very difficult for the students to see their notebooks and practically impossible to see the blackboard.

Admirably, the children and the teachers keep on working, making use of their laptops, which run on the batteries that are charged on the solar gang charger. However, we have had no Internet connection for over two weeks due to lack of electrical power.

Update VII: The Light Up Nigeria Facebook group – started only a few days’ ago – now has over 4000 nearly 7000 members…

Update VIII: There are some eye-catching figures in the 2004 Strategic Gas Plan for Nigeria.

By a conservative estimate, 30% of Nigeria’s electricity is produced by private generators. Despite its monopoly position, NEPA (or the Power Holding Company of Nigeria) produces less than half of the total, largely due to its gross inefficiency. Total supply (private generators included) is running at only around 75% of current demand (e.g. not including all those who are off grid).

If NEPA could get all its existing capacity working again and cut transmission losses to 25% (still high by global standards), it could meet 87% of current demand, without the need for private generators.

One additional medium-sized gas power plant would comfortably ensure all existing demand was met. Build eight more by 2020 and a 6% annual growth in demand would be satisfied. By 2040, Nigerians would be consuming as much electricity as Mexicans do today.

Where’s this gas to come from? That should be easy. Nigeria is thought to have 5% of the world’s gas reserves (the same again may be undiscovered). Unfortunately, a huge proportion of Nigeria’s gas is being wasted. In 2004, 55% of Nigeria’s gas was flared – simply burnt off as it comes out of the ground. This gas was worth $2.5bn and is equivalent to the entire annual power generation for sub-Saharan Africa.

Flaring has a disastrous impact on the Niger Delta, where unrest is costing Nigeria $20bn a year. According to one report:

Communities who live near Nigeria’s more than 1,000 onshore well heads are blighted by gas plumes that rise from the ground, spreading toxic smoke and chemicals over their farms…”When you approach a gas flare, the first thing you notice is the heat, the villages around the flares are all very hot.” The flames also light up the sky 24 hours a day, and the noise that comes from them is a continuous roar like a jet aircraft taking off…

Doctors have reported higher rates of cancer, children with asthma and a suggestion the burning gasses may be making residents infertile.

And one last figure for you. In 2004, Nigeria’s flared gas was estimated to cause 70 million tonnes of CO2 emissions – that’s roughly equivalent to the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by Austria! Simply stunning.